Introduction

The right to use and sell property as the owner sees fit is necessary for any society to facilitate voluntary exchange. If property rights are protected, there can be positive impacts to the nation’s economy. Some economists argue that the right to property is a factor in the success of a nation’s per capita growth rate. One study found that countries that protect property rights grow more quickly than those that do not. Protecting the right to use one’s property as they see fit is important and has advantageous effects beyond initial intent.

In their article on the future of development regulation, two Florida State University researchers explain that the current framework for regulating private land use is a closed system, in which new procedures must reflect the local comprehensive plan or be supported by a political majority. They advocate instead for an open system in which innovations are adopted so long as their implementation does not restrict the right of another to use their property as they see fit.

Take, for example, a situation in which an individual wants to build a stage in their backyard and the lights shine into their neighbor’s yard. If the neighbor did not want light shining in his yard, this would impede his right to use his property as he desires. If, instead, the individual’s lights did not shine into the neighbor’s yard and the neighbor protested the building of the stage because he didn’t like the way it looked, this is not a valid reason to prohibit the individual from building because it does not prevent the neighbor from using their own property as they please. This framework is more dynamic in nature than creating strict restrictions to address all possible conflicts that can occur. It also protects the right to property by ensuring that one person’s desires for usage are not obstructing another’s.

Zoning policies broadly regulate the use of land and the nature of development that is allowed within designated areas. Zoning in the United States emerged in the early 20th century as a response to overcrowding and unsanitary conditions resulting from the rapid industrialization of American cities.

Under the leadership of then-Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover, advisory committees developed two model policies in the 1920s that laid the foundation for contemporary zoning practices across the country. The Standard State Zoning Enabling Act (SZEA) was first published in 1924, followed by the Standard City Planning Enabling Act (SCPEA) in 1927.

Traditionally, zoning has followed a single-use model wherein areas are reserved for only commercial, residential, or industrial use. This approach to zoning is referred to as “Euclidian zoning” (named after Euclid, Ohio, not the Greek mathematician).

The 1926 U.S. Supreme Court decision in The Village of Euclid v. Ambler provides the constitutional basis for governments to designate the permissible uses of land. The primary goal of Euclidian zoning was to improve health and safety conditions in congested and dirty cities by separating residential from industrial areas. However, zoning policies were also used to enforce geographic segregation between racial and socio-economic groups.

In contrast to traditional Euclidian zoning, mixed-use zoning allows for multiple uses in a particular area or building. Today, commercial developments do not typically present significant health, safety, or environmental threats. Proximity of housing to commercial development is also considered a desirable amenity among consumers. In fact, urban planners of the 21st century have enthusiastically embraced mixed-use development, often citing environmental and health benefits of walkable urban environments.

In jurisdictions that still rely on traditional Euclidian zoning, developers are generally required to obtain a conditional use permit or request a use variance to create mixed-use developments. The processes for obtaining these special permissions result in uncertainty, enable opposition by vocal community stakeholders, and enable special interests to hinder development.

One solution to this problem is to change the underlying zoning code to allow for more than one use. For example, some municipalities have zoning designations that specifically allow mixed-use development.

Many single-family zoning districts do not allow any variations such as granny flats or additional dwellings on the property. Many oppose these units due to traffic or “neighborhood character” concerns. Often zoning boards will recommend denying exceptions to all properties under the rationale that if they offer an exception to one party, they must offer it to all parties.

But for homeowners, zoning can represent a taking of property rights, especially when it becomes overly restrictive. Clearly, zoning exceptions need to be considered on a case-by-case basis. Yet, with housing costs outpacing incomes, particularly in geographically constrained metro areas, the takings element deserves greater consideration. an unnecessary one, states across the political divide have been working to reform zoning laws, types of dwellings, problematic policies, growth restrictions, lot sizes, and parking requirements.

In addition to zoning restrictions, other regulations seek to reduce housing costs by pressuring developers, in some cases requiring them to sell a portion of their buildings for lower prices (often called Inclusionary Zoning or Affordable Dwelling Unit ordinances) — often lower than the costs of building them.

While such requirements might sound like a logical way to reduce housing prices, coercing developers in this way can be counterproductive. These kinds of policies have proliferated as both housing prices and interest rates reach multi-decade highs.

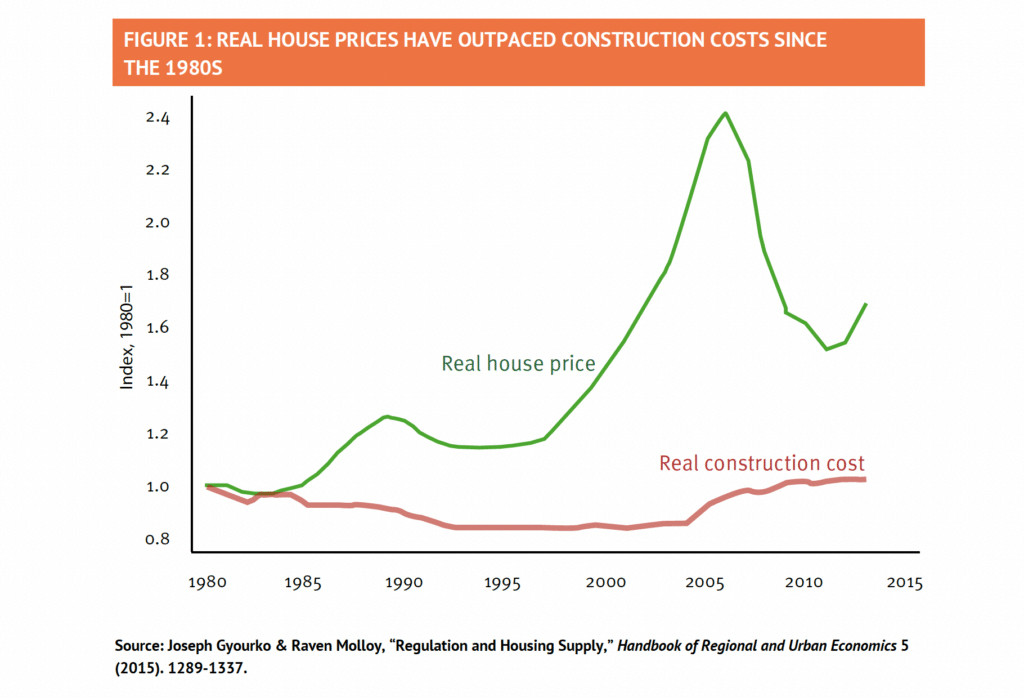

Over recent decades, house prices have risen faster than construction costs (such as building materials and labor). For example, research found that, after controlling for inflation, construction costs remained relatively stable between 1980 and 2013.

However, housing prices rose sharply over the same period (Figure 1).

Economists have generally attributed this divergence to regulatory costs. Regulatory requirements add to the cost of housing by restricting supply, imposing fees, and creating delays in the construction process. A 2021 report found that regulatory costs add an estimated 23.8% to the final sale price of a home. This equates to an average of $93,870 for each house. (These are the costs for land use charges such as zoning and architectural designs not structural inspections).

These regulations are one factor in the rapid increase of housing costs.

Figure 1 shows how, over the last 30 years, housing prices have risen almost twice as fast as real construction costs.

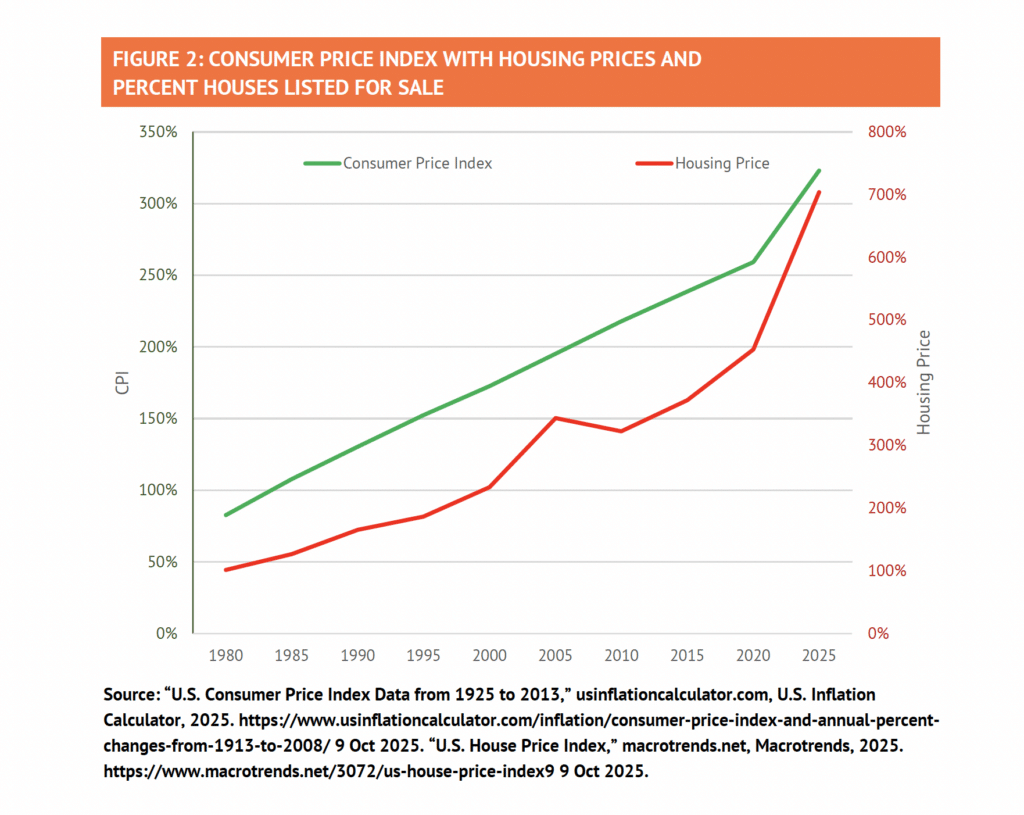

Figure 2 shows that, even with rapid inflation of consumer goods in recent years, housing prices have still been rising faster than inflation as a whole.

Between 1980 and 2025, consumer prices increased just under 300%, which sounds excessive. But during that same time period, housing prices increased almost 600%, or roughly twice as fast.

Regulations play a large part in the run-up of prices. They act as a form of taking. Regulations restrict how landowners can use their property and diminish the value of the land. Many serve no real purpose other than to abide by zoning rules, many of which have not been reviewed in more than 50 years.

Recognizing that regulatory costs are a major driver of high housing costs, and in many cases an unnecessary one, states across the political divide have been working to reform zoning laws, types of dwellings, problematic policies, growth restrictions, lot sizes, and parking requirements.

Full Report — Annual Privatization Report 2025: Housing