Executive summary

Despite declining student enrollment in many U.S. school districts, K-12 education spending and staffing—particularly in non-instructional roles—have grown substantially over the past two decades.

This paper investigates the political and institutional drivers of this trend, focusing on the influence of teachers’ unions in shaping staffing decisions, resisting reform, and reallocating resources in ways that often fail to improve student outcomes. Using longitudinal data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), the study reviews evidence showing that staffing growth is concentrated in non-right-to-work states where union density is higher.

These increases are further concentrated in non-teaching roles and are not associated with gains in student achievement. Empirical evidence suggests that strong union presence tends to prioritize employment protections and compensation structures that inhibit performance-based pay and flexibility in resource allocation.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, unionized school districts were also slower to return to in-person learning, exacerbating academic and mental health setbacks for students and parents alike.

The paper also reviews education reform efforts, such as performance pay for teachers and school choice programs, that can help improve educational outcomes by aligning incentives and improving the efficacy of spending.

The evidence broadly suggests that the effectiveness of additional funding depends less on its amount than on its use. Systems with weak accountability or entrenched union influence are more likely to channel resources toward administrative expansion rather than classroom quality.

Ultimately, improving educational outcomes requires aligning incentives, empowering parents with real choices, and ensuring transparency in how funds are spent. Education reforms that prioritize instructional quality, flexible governance, and accountability, rather than mere staffing, will produce meaningful gains for students.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, K-12 education in the United States has seen a striking increase in staffing and public funding, despite enrollment declines in many districts. This phenomenon has provoked growing concern among policymakers, parents, and researchers alike: Why, in districts that serve fewer students, are school systems simultaneously hiring additional non-instructional staff?

While modest expansions in school administrators or support personnel may reflect growing student needs or regulatory requirements, the scale of these staffing surges raises questions about whether limited educational resources are being optimally deployed to boost student achievement. Indeed, while expenditures and staff-to-student ratios have soared, academic outcomes—particularly in reading and math—have remained disappointingly flat.

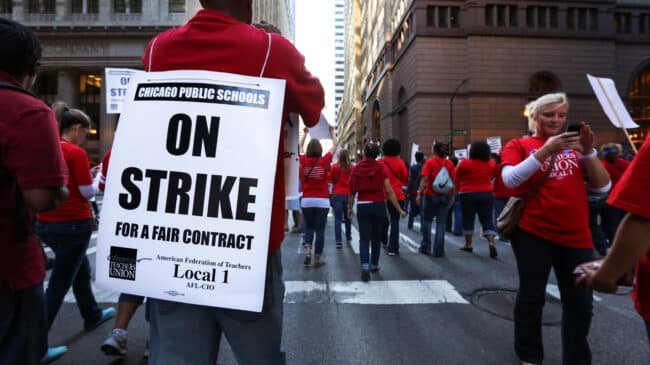

A leading hypothesis for this apparent misalignment is the influence of teachers’ unions on local budget decisions and staffing patterns. Historically, unions have sought higher wages and smaller class sizes, but a new wave of research suggests they may also lobby for broader personnel expansions that are unrelated, or weakly related, with driving educational outcomes.

Drawing on data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), my research finds that states without right-to-work laws (RTW)—where unions can require membership—are far more likely to exhibit robust staffing growth relative to states that weaken collective bargaining. Unions are involved in other facets of district management, from school reopening decisions during the COVID-19 pandemic to the distribution of any incremental funding that flows into schools. While strong unions can serve teacher interests and potentially enhance job quality, critics argue they also impede certain reforms—such as performance-based pay—and reinforce a “one-size-fits-all” salary schedule that may crowd out more-effective uses of resources.

Against this backdrop, this study synthesizes findings on how union influence, evolving staffing patterns, and student performance intersect in the U.S. K-12 landscape.

Building on the decades-long “staffing surge,” the policy brief examines how expansions of non-teaching roles can persist even when student enrollments decline, highlighting both the organizational challenges and union-driven motivations that drive this growth. It also explores the empirical literature on reform strategies—spanning performance-pay policies, school choice options such as charters, vouchers, and education savings accounts (ESAs), and shifting accountability regimes—that aim to re-align resource allocation to improve student outcomes.

Recent debates on COVID-19 school closures further illustrate how collective bargaining powers can shape schooling decisions in ways that are not always aligned with empirical evidence on academic and mental health trade-offs.

Ultimately, the evidence underscores that, while more funding may sometimes have slightly positive effects, the magnitude is small and depends much more heavily on the composition of spending, accountability structures, and degree of competition in the ecosystem.

Full Policy Brief: Staffing surges and student outcomes: Rethinking unions, resource allocation, and school choice in American education

Download this Resource

Staffing surges and student outcomes: Rethinking unions, resource allocation, and school choice in American education

Thank you for downloading!