In a 2009 TED Talk, Director of the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory and Google Vice President Sebastian Thrun set off a firestorm of interest over automated vehicle technology in his announcement that Google was pursuing a world where human beings no longer drive cars.

Since then, Google has been joined by numerous technology startups as well as traditional automakers in a joint quest to replace human beings in the driver’s seat with sensor arrays and computers.

A key issue facing both developers and policymakers is ensuring clear communication about the various technologies and features.

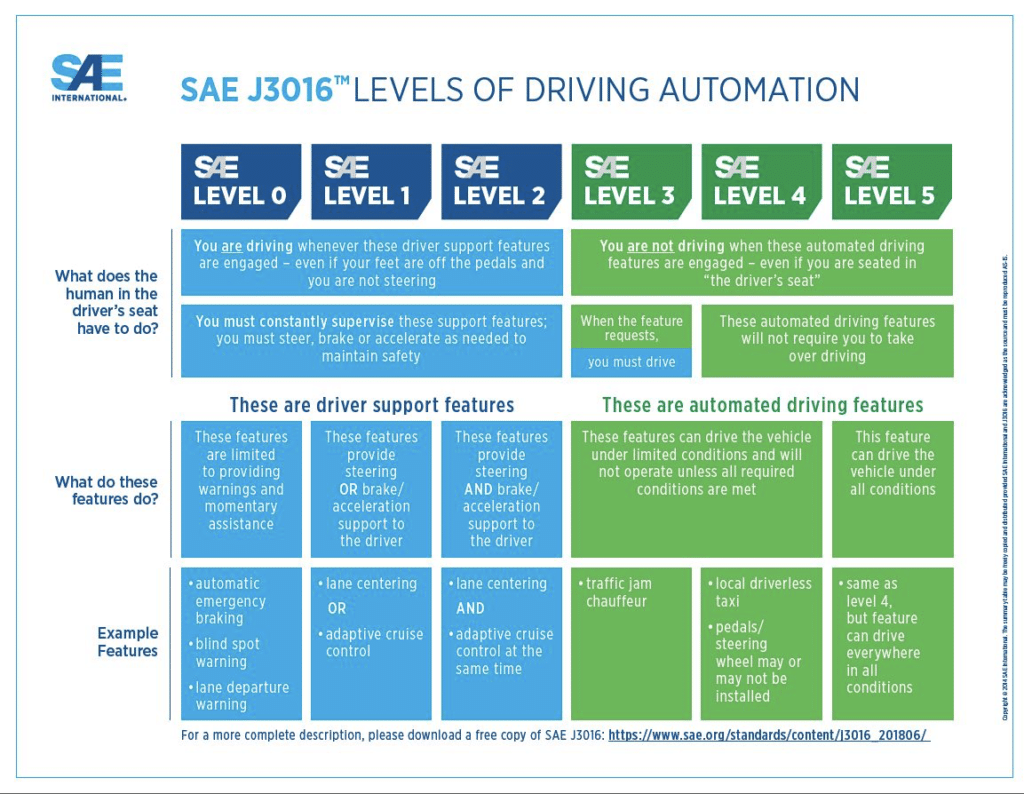

Policymakers have also taken interest in these new technologies. A key issue facing both developers and policymakers is ensuring clear communication about the various technologies and features. Fortunately, vehicle automation definitions have been standardized by SAE International through Recommended Practice J3016.

When the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration published its first formal automated vehicles guidance policy in 2016, it abandoned its 2013 levels of automation in favor of those defined in SAE J3016. Congress has also adopted SAE, most formally in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021.

States and local policymakers are now generally using SAE J3016 levels of automation as well. SAE International has produced the graphic in Figure 1 to aid policymakers and the public in understanding technology capabilities and driver responsibilities at various levels of automation.

Rather than mere driver assistance provided by lower levels of automation, an automated driving system (ADS) at SAE Levels 3–5 automates the entire driving task. It is here where the traditional relationship between automobiles and human operators breaks down, most of the potential benefits from automation can be realized, and policymaker attention is most warranted.

Improving safety has been a top-stated priority of ADS developers and is especially significant given the long-recognized fact that more than 90% of automobile crashes involve driver error or misbehavior. The technology also offers great promise for traditionally mobility-disadvantaged groups who—either by disability or lack of income— are unable to drive their own vehicles and then suffer the consequences of reduced access to jobs, medicine, and leisure that poor substitutes such as mass transit cannot come close to matching.

ADS-equipped vehicles also have the potential to significantly reduce traffic congestion and improve the flow of freight. Brookings Institution economist Clifford Winston and lawyer Quentin Karpilow modeled the economic impacts of congestion reduction in a scenario of widespread ADS adoption in their book, Autonomous Vehicles: The Road to Economic Growth?

They estimate that a large reduction in travel delays could raise the annual economic growth rate of the U.S. by at least one percentage point. While this might seem small, a conservative estimate would still translate to hundreds of billions of dollars in additional annual growth to the economy.

Widespread deployment of ADS-equipped vehicles remains years away. Policymakers would be wise to begin preparing for this future today because the automotive safety regulatory framework will also take years to update. Congress’ last serious attempt at enacting comprehensive national ADS policy occurred in 2017 and 2018 during the 115th Congress. This effort ultimately failed. Since then, ADS-related regulatory activity at the U.S. Department of Transportation has slowed.

This policy brief aims to provide the 118th Congress with guidance so it can reinvigorate and refocus federal ADS policymaking on productive near-term activities.

Part 2 discusses how Congress can ensure ADS-related policies are developed in a sound manner.

Part 3 explains the need for temporary regulatory relief and how Congress can simultaneously promote technological innovation while maintaining the high level of safety demanded by the public.

Congress has a difficult task ahead of it in crafting policies to support the development and deployment of automated driving systems. The large amount of uncertainty surrounding developer testing progress, deployment dates, and technical standardization complicates this process. However, despite this uncertainty, Congress can chart a responsible path forward. With small amendments to existing statutes, Congress can prepare federal regulators who are tasked with implementing policy and ensuring that a high level of safety is maintained.

The recommendations contained in this brief should be viewed as “no regrets” policies that can be undertaken with minimal risk to either automated driving system development or the public interest. Modernizing the regulatory framework to allow for the more rapid uptake of technology knowledge must be paired with the recognition that this effort will take time to bear fruit, which necessitates a related modernization of exemptions from that regulatory framework as a safety valve.

Going forward, there will be much more policymaking and fine-tuning of existing policies to better match the technological, economic, and social issues that may arise from automated driving system deployment.

Fortunately, while the pace of development has been rapid, policymakers still have plenty of time to get policy right to maximize the benefits of the technology.

Full Brief: Automated vehicle policy recommendations for the 118th Congress