School finance reform is a priority for many state legislatures. Pennsylvania, for example, has had an antiquated funding system for more than two decades and is close to adopting a weighted-student formula that would distribute funds more equitably among districts. This, however, represents only half of the equity equation.

For their part, districts must ensure that funds are distributed equitably among schools and empower principals to allocate resources according to the unique needs of their students. Simply stated, equitable funding doesn’t stop at the district level-it must be pushed down to the student level. Unfortunately, most school districts use a Full-Time Equivalent (FTE) budgeting system that fails to do this.

With 35,000 students across 46 schools, Spring Branch Independent School District (SBISD) in Texas provides a good case study to illustrate how FTE budgeting might contribute to inequitable student funding. It’s important to note that this situation is not unique to SBISD; in fact, recently retired SBISD Superintendent Duncan Klussman was a visionary leader and had a demonstrable commitment to serving disadvantaged student populations through innovation as a recent Center for Reinventing Education report documents. Instead, it’s a widespread problem of how districts allocate and use resources.

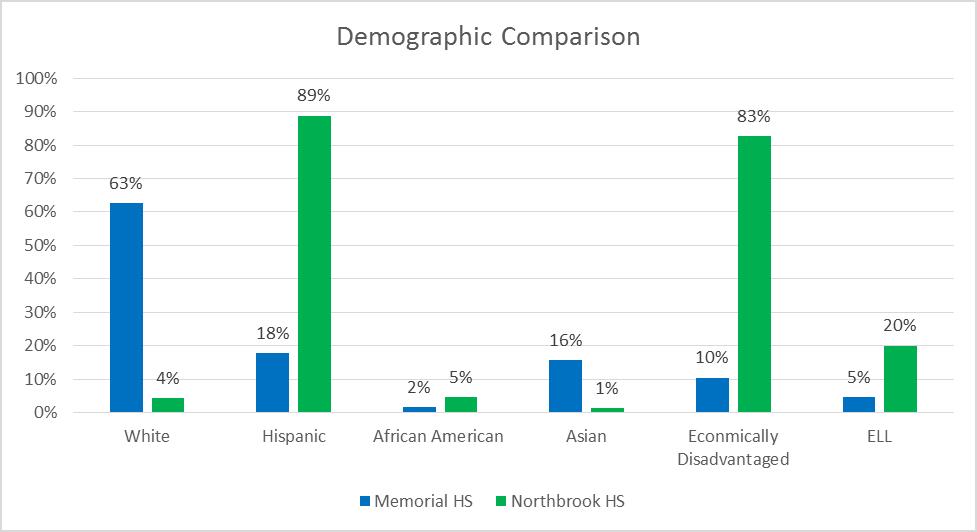

SBID’s Northbrook High School (NHS) and Memorial High School (MHS) are a mere three miles apart yet light-years away in terms of demographics. Although they have similar membership counts of 2,145 and 2,563, respectively, NHS has significantly more economically disadvantaged and English-language learner (ELL) students. These populations generally present greater challenges for educators.

Source: 2013-14 Texas Academic Performance Report, downloaded July 2015

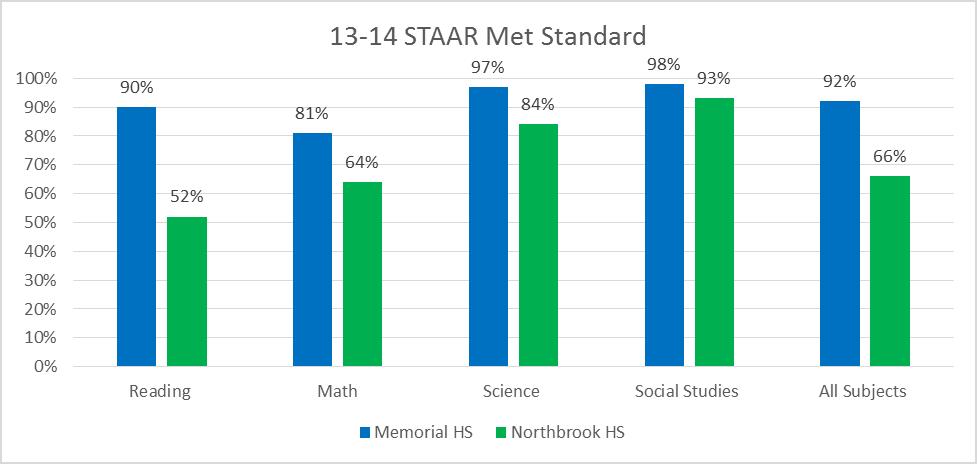

The challenges facing NHS are clearly demonstrated by its inferior academic outcomes. This is especially evident in reading where only 52 percent of NHS students passed the state’s English I and English II exams, compared with 90 percent for MHS.

Source: 2013-14 Texas Academic Performance Report, downloaded July 2015

At first glance NHS does, in fact, receive more resources, as it spends $6,248 per pupil in total operating expenditures compared to $5,557 for MHS. Whether a $691 per pupil funding gap puts NHS on equal footing with MHS is beyond the scope of this piece. Instead, the focus is on how these funds are allocated and used, which can easily negate any equalization achieved from surplus funding.

First, it’s important to understand that in FTE budgeting, schools are given the bulk of their resources by way of staffing positions. Instead of receiving actual dollars to allocate flexibly based on student needs, they’re provided with staffing positions based on rigid ratios. A district with a 25:1 student-to-staff ratio would provide resources as follows:

| School #1 | School #2 | |

| Students | 50 | 74 |

| Teachers | 2 | 2 |

If School #1 had enrolled just one less student it would have lost a staffing position. Similarly, if School #2 had enrolled just one more student it would have received an additional staffing position. This creates a rather “lumpy” distribution of resources among schools, which contributes to inequities.

This problem is compounded by the fact that districts often charge school budgets average salaries instead of actual salaries. For example, assume that the district’s staffing-ratio dictates that each school receives one teacher. Based on the district’s salary schedule the teachers are compensated as follows:

| Teacher A | Teacher B | |

| Years of Experience | 1 | 25 |

| Actual Salary | $47,000 | $62,650 |

| Avg. Teacher Salary | $54,825 | $54,825 |

Now assume that Teacher A works at School #1 and Teacher B works at School #2.

| School #1 | School #2 | |

| Actual Teacher Salary | $47,000 | $62,650 |

| Charge to Budget | $54,825 | $54,825 |

| Net | ($7,825) | $7,825 |

Since School #1 is charged the district’s average teacher salary instead of the actual salary for Teacher A, it essentially provides a $7,825 subsidy to School #2. Given that a) Teachers are paid the same regardless of where they teach in a district, and b) School budgets are charged the same salary regardless of who they hire, it follows that schools in wealthy communities tend to have more experienced teachers to the detriment of schools in poor communities. Beyond goodwill there is little incentive for teachers to work at more challenging schools and there is a significant incentive for principals in wealthy communities to hire the most expensive teachers when they aren’t being charged for actual salaries.

It should be noted that while inexperienced teachers can, in fact, be more effective than their seasoned counterparts (e.g. Teach for America corps members who are provided with exceptional training and support) the general trend is clear: schools in wealthy communities often attract more effective teachers whose salaries are subsidized by schools in poor communities.

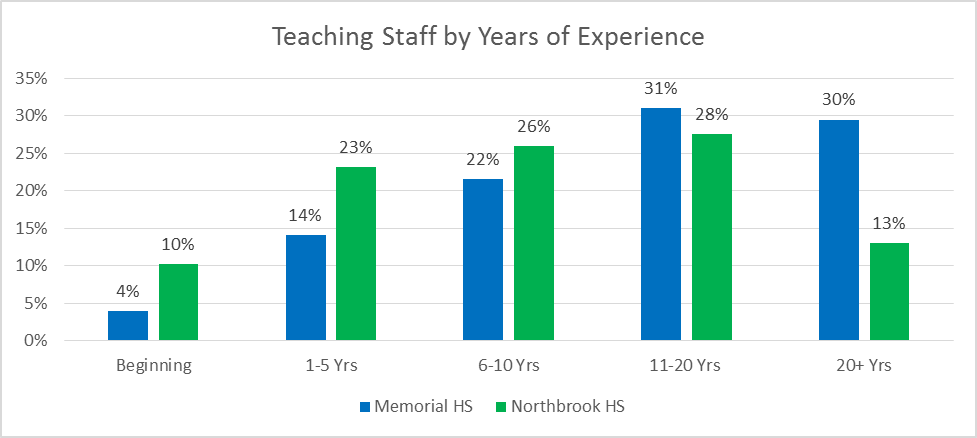

For Spring Branch Independent School District, this plays out precisely as you would expect: Northbrook High School teachers are far less experienced than their counterparts at Memorial High School even though the NHS student population provides greater challenges.

Source: 2013-14 Texas Academic Performance Report, downloaded July 2015

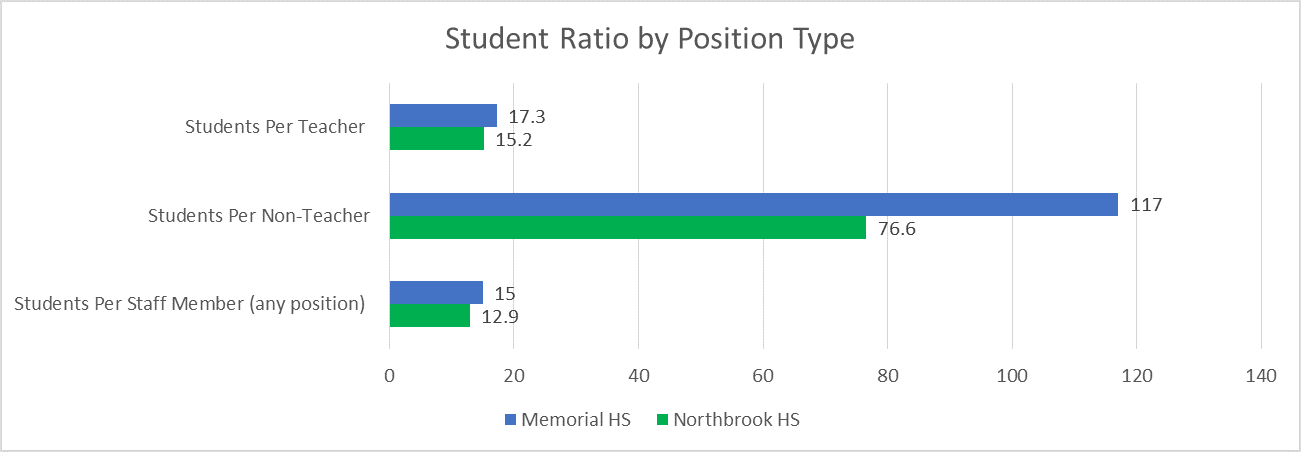

Additionally, there are significant differences in what staff members at NHS and MHS actually earn, even though their budgets are charged the same amount for each position. NHS, in effect, subsidizes higher actual salaries at MHS.

Source: 2013-14 Texas Academic Performance Report, downloaded July 2015

As noted earlier, compared to Memorial High School, NHS spends more money per pupil yet has a less experienced and cheaper staff. So where are its additional resources going? Most are likely distributed through programmatic allotments, such as special education, which are generally quite restrictive in how they’re used. This appears to be mostly in the form of non-teaching staffing allocations as shown in the graph below. Interestingly, NHS spends $417 more per pupil on special education yet $428 less per pupil on regular education than MHS.

Source: 2013-14 Texas Academic Performance Report, downloaded July 2015

The fundamental problem is that SBISD principals have little control over resource allocation. According to the Center for Reinventing Education, the district sets and distributes about 85-90 percent of school budgets. Instead of receiving funds to spend flexibility based on student needs, schools leaders must abide to rigid staffing formulas and district office mandates. For example, SBISD requires each school to offer sports, band, and arts programs-while these activities certainly have value, such decisions should be left to principals.

SBISD provides an example of how inequities can persist even if states allocate funds to districts in an equitable manner (which Texas does not). The solution to this is straightforward: allow funds to follow students to the school level and provide principals with actual dollars to spend based on student needs. In turn, principals should be provided with extensive training and support to help facilitate this transition. The antiquated FTE system that uses staffing ratios and average salaries should be eliminated and replaced with student-based budgeting.

Aaron Smith is an education policy analyst at Reason Foundation.