What is environmental, social and governance?

ESG generally refers to the focus on environmental, social and governance issues that are considered by investment managers, financial and banking firms, and activist interests when they are measuring risks and opportunities.

When paired with standard financial forecasting, the ESG lens can help money managers find risks and opportunities not accounted for in an asset’s market price. However, when ESG is used to push capital towards or away from assets according to political preferences that are independent of financial considerations, ESG investments can become a type of political contribution.

Credit rating agencies and other firms continuously develop new ESG ratings that attempt to financially assess the societal impact of public corporations across these three—environmental, social and governance—factors. These ESG ratings and other ESG-centered investing and risk mitigation strategies have gained significant traction among major asset managers and institutional investors looking to maintain investment revenue.

Common ESG areas of focus currently include:

| E | S | G |

| Environmental | Social | Governance |

|

|

|

The proliferation of ESG activism is generating significant controversy in many states because of its potential implications on market capitalism and how it may impact prospects in many industry sectors. In some cases, activist investors attempting to shape society and the economy according to their own aspirations look to create large pools of private and public funds to target companies they may deem detrimental to their ideal society. Energy companies, agricultural firms, tobacco companies, gun manufacturers, correctional service providers, and other industries have been among the targets. There is a growing and legitimate concern among many public officials that activists are using ESG-related risk mitigation rhetoric and branding to raise money from state treasury funds, public pension funds, and other public trusts for political use, which runs counter to longstanding fiduciary norms.

Contextualizing ESG policies is inherently complicated. For example, is ESG simply investors considering the genuine financial risks associated with a company’s actions on environmental or social issues, or is it a recklessly so-called ‘woke’ use of capital to push political goals?

A public pension fund considering sea level rise when weighing an investment in waterfront commercial real estate is prudent investing. Similarly, ensuring that a company’s labor force is content and that supply chains are sustainable is sound management. By contrast, using taxpayer money to allocate resources to companies and projects based on political ideology crosses the line into activism and violates fiduciary standards requiring a singular focus on maximizing market returns to ensure that public pension benefits will be fully funded, for example.

While taking many forms, ESG activism can be broadly described as stakeholder capitalism, a modern form of corporatism, which suggests that rather than serving shareholders, companies should aim to serve the interests of all potential stakeholders. Different from shareholder capitalism—where the goals and sole considerations are focused on returns to the owner of an investment—stakeholder capitalism is based on amorphic political and ideological objectives.

Increasingly, activist entities within traditional financial services organizations like banks, fund managers, and institutional investors are using the hundreds of billions of dollars in taxpayer money they manage to promote stakeholder capitalism ideology. This uses public resources to promote the activists’ political goals and distorts the free market.

BlackRock Chairman and CEO Larry Fink outlined his view in his 2022 letter to CEOs of the companies BlackRock’s clients invest in:

“Stakeholder capitalism is not about politics. It is not a social or ideological agenda. It is not ‘woke.’ It is capitalism, driven by mutually beneficial relationships between you and the employees, customers, suppliers, and communities your company relies on to prosper. This is the power of capitalism.”

Mr. Fink’s suggestion that this activism is based on universally-shared interests is questionable at best. ESG policies often take sides on some of our time’s most contentious political issues, including environmental and energy policy, foreign policy, abortion, and guns, to name just a few. ESG activists often attempt to move these types of issues from the democratic and judicial processes to private financial markets and corporate boards, politicizing what have, in many cases, historically been non-political organizations and institutions.

How does ESG enter public finance?

The largest pools of state-managed capital are usually public pension funds and trusts. Large state pension plans and treasuries are essentially large institutional investors in the market, similar to a university endowment or insurance fund. These trusts are operated by boards of trustees with their own personal perspectives and biases on ESG issues. In the government context, there is a long history of politicians encouraging or even directly mandating particular types of corporate investment or divestment in states like California, New York, and Texas.

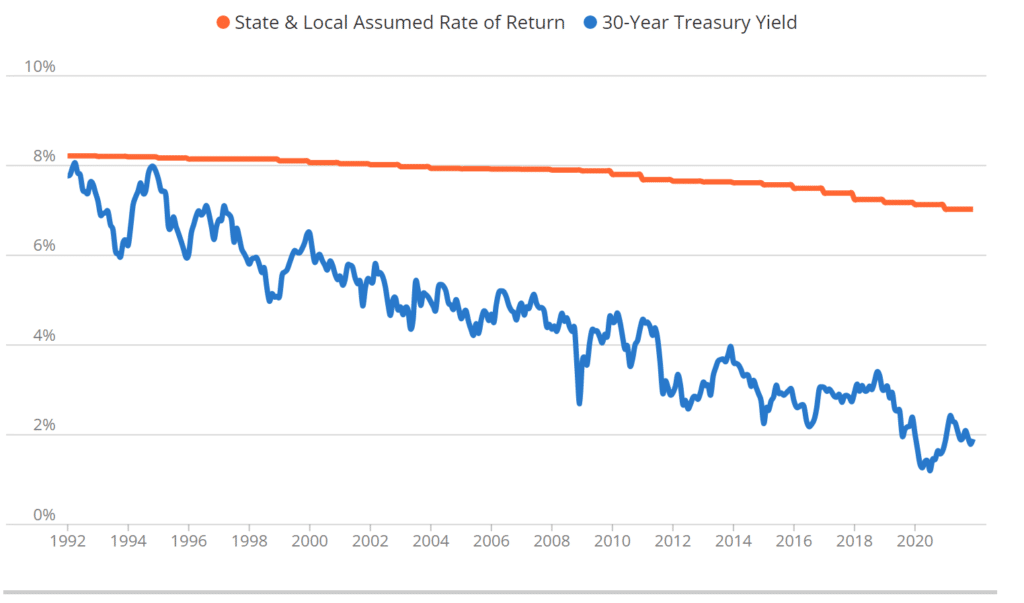

Before the year 2000, multi-billion dollar public pension funds historically relied on revenue generated by traditional, low-risk assets such as government bonds and blue-chip stocks that paid investment returns and dividends that kept pension plans’ costs low while they funded constitutionally-protected retirement benefits of public workers. However, as capital market outlooks diminished in the wake of a historic drop in global interest rates, multiple recessions, and growing stock market volatility, public pension plans were slow to adjust their investment return assumptions downward (see figure below), contributing to the more than $1 trillion in unfunded public pension liabilities today and growing pressure on public pension fund managers to pursue higher investment returns.

The Average U.S. Public Pension Plan’s Assumed Investment Return Rate

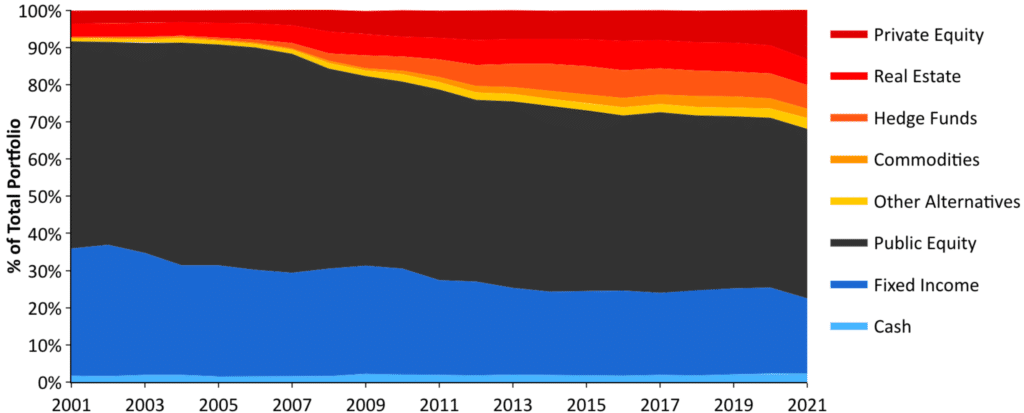

For many U.S. public pension systems, the large gap between their overly optimistic investment return assumptions and risk-free bond yields has created growing pressure on pension fund managers to take on more risks via actively managed alternative investments, such as private equity, hedge funds, private real estate, private debt, natural resources, and other non-traditional assets. The figure below shows that alternative investments among all U.S. public pension funds have increased from 9% in 2001 to 29% in 2021.

Average Asset Allocation Within U.S. Public Pension Investment Portfolio

Many of these alternative investments are not transparent, carry additional financial risks and incur significant fees from outside money managers.

Notably, the private and opaque nature of alternative investment valuation and reporting also creates an opportunity for politicizing public pension fund investments without the approval of the pension system’s trustees.

Who are the major players in ESG?

BlackRock, State Street Corporation, The Vanguard Group, AllianceBernstein, Nuveen, and PIMCO are some of the largest U.S.-based financial managers involved in marketing and executing ESG-related investment strategies. The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) and large public sector labor unions, such as the American Federation of Teachers, also push their members who serve as trustees to have those organization investments adhere to environmental, social and governance standards. This is in sharp conflict with pension plans’ duty to make fiduciary decisions in the sole interest of maximizing investment returns to ensure that all of the pension benefits promised to and earned by members will be fully funded.

Additionally, there are groups like the Ceres Investor Network on Climate Risk and Sustainability, which says it “includes more than 220 institutional investors managing more than $60 trillion in assets” as it works “with our members to advance sustainable investment practices, engage with corporate leaders, and advocate for key policy and regulatory solutions to accelerate the transition to a just, sustainable, net zero emissions economy.”

Another group is Climate Action 100+, which says it “is an investor-led initiative to ensure the world’s largest corporate greenhouse gas emitters take necessary action on climate change.”

The map below identifies the public entities—state and local—that have signed on to Ceres and/or Climate Action 100+. You can click on individual states to see the public entities that have joined these groups.

Why are ESG strategies problematic for taxpayers and public pension systems?

Although ESG is often touted as a risk mitigation strategy by its proponents, ESG activism that prioritizes political objectives over maximizing investment returns enhances the risk of underperformance for public pension system investments. This risk ultimately falls on taxpayers, who would pay for public pension shortfalls through higher taxes and contributions to the system.

Activism in institutional investing also creates arbitrary standards that are easy to manipulate. ESG investing currently lacks universally agreed-upon standards, allowing activists to create their own performance benchmarks lacking consistency, objectivity, and accountability. Being the largest investment pools funded primarily with taxpayer money, public pension systems and trusts are particularly exposed to the risk associated with activist investing.

In The Wall Street Journal, Terrence R. Keeley, a former Blackrock senior executive, wrote:

“Trillions of dollars have poured into environmental, social and governance funds in recent years. In 2021 alone, the figure grew $8 billion a day. Bloomberg Intelligence projects more than one-third of all globally managed assets could carry explicit ESG labels by 2025, amounting to more than $50 trillion. Yet for a financial phenomenon this pervasive, there is astonishingly little evidence of its tangible benefit.”

In examining the evidence for whether being socially responsible is creating value for companies and investors, Bradford Cornell, professor emeritus at the Anderson Graduate School of Management at the University of California-Los Angeles, and Aswath Damodaran, a professor at the Stern School of Business at New York University, wrote that “telling firms that being socially responsible will deliver higher growth, profits and value is false advertising.” The researchers concluded that “evidence that investors can generate positive excess returns with ESG-focused investing is weak.”

In a 2022 working paper for the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University, other researchers conclude:

“We find that while ESG ratings providers may convey important insights into the nonfinancial impact of companies, significant shortcomings exist in their objectives, methodologies, and incentives which detract from the informativeness of their assessments.”

Private individuals and institutions are free to allocate their assets in whatever ways they see fit. Publicly sourced assets, however, are a different story. Public pension funds have a fiduciary duty to manage assets in ways that ensure they have funding to provide all of the retirement benefits promised to their members. The subjective, non-pecuniary nature of ESG activism is inconsistent with these fiduciary responsibilities and the objectives of public sector retirement systems.

The over $5 trillion in state and local public pension assets is not something to be leveraged for political causes by plan participants or administrators. Unfortunately, rather than focusing on their responsibility to fully fund public pension plans, too many public entities are increasingly becoming activists on ESG and other political issues.