The Wyoming legislature passed two pension reform measures this year that promise to improve the sustainability of the state’s retirement system. The action became imperative as the state faced a declining bond rating and historically low funding levels at Wyoming Retirement System’s Public Employee Pension Plan.

Wyoming House Bill 109 phases in higher statutory employer and employee contributions over the next four years. By Fiscal Year 2022, both employers and employees will each pay 1 percent of payroll more than they do today. The legislation prevents employers from picking up the extra employee contributions, saving budgetary resources and ensuring balance in how increased contribution rates are applied.

A second measure, House Bill 110, improves pension plan solvency by changing the rules around lump sum payments made to employees who leave the system prior to vesting. Previously, the lump sum payment would include all employee contributions plus interest. Under the reform, employer pickups (employee contributions paid by the employer) will no longer be included in the lump sum payments. Legislative analysts estimate that the reform will save the Public Employee Pension Plan $3.5 million in Fiscal Year 2021.

Although Wyoming’s population is relatively small, the Wyoming Retirement System (WRS) is a relatively large system because it covers virtually all state and local employees and because Wyoming has relatively high rates of government employment. According to 2014 Census data, Wyoming had 160 state employees per 10,000 residents compared to just 61 in neighboring Colorado.

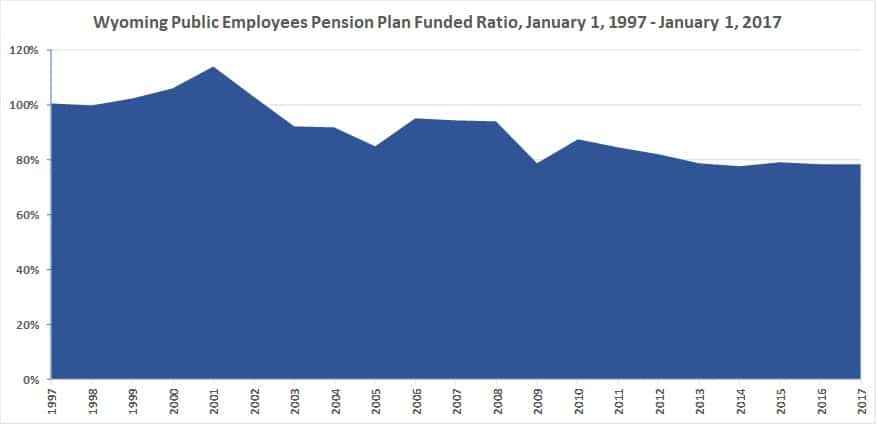

Unfortunately, WRS’s financial situation has become more precarious since the start of the century. At the beginning of 2001, WRS’ Public Employee Pension Plan —far and away the biggest— reached a peak funded ratio of 113.8 percent. As the accompanying chart shows, the ratio then began a precipitous decline, stabilizing at much lower levels in recent years. At the beginning of 2017, the plan’s funded ratio had fallen to just 78.1 percent. Due to its declining condition, WRS has not granted its beneficiaries Cost of Living Adjustments since 2008. Last May, Standard & Poor’s lowered the state’s Issuer Credit Rating from AAA to AA+ citing “weaker pension funded levels” as one of the causes. S&P took the action despite the fact that the state only has $23 million in outstanding bonded debt, accounting for just 0.06 percent of Gross State Product.

Source: Wyoming Retirement System Actuarial Valuation Reports

New actuarial reports to be released in mid-June should show a further decline in funded position. The benefits of strong investment returns —estimated at 14.2 percent— will be more than offset by the effects of WRS’ decision to lower its assumed rate of return from 7.75 percent to 7.00 percent. Although this move increases the system’s reported pension liabilities, it is a prudent measure that sets WRS on a course for long-term improvement. A more realistic long-term investment return assumption will yield more accurate financial reporting which can support better decision-making.

Although the state has implemented reforms over the years, these measures have yet to reverse the decline in funding levels. But House Bills 109 and 110 promise to turn the tide.

State Rep. Donald Burkhart, Jr., speaker pro tempore of the Wyoming House, helped move the two reform measures. In a recent interview, Burkhart told me that he and his colleagues are working on additional fiscal sustainability measures. For example, the state legislature is using the budget process to reduce health insurance subsidies.

This is welcome, because WRS may need more legislative attention going forward. One reason that the Public Employee Pension Plan became underfunded is that the state and other employers did not make their full Actuarially Determined Contributions (ADEC). For example, statewide contributions to the plan in 2016 amounted to 8.50 percent of covered payroll, well below the 9.77 percent recommended by actuaries, which resulted in a $23 million contribution deficiency.

Increasing statutory contributions reduces this problem but does not necessarily eliminate it. As the actuary begins applying a lower discount rate, ADECs will rise and there is no assurance that the higher statutory contributions will be sufficient. A better practice —and one followed in many states— is to require employers and employees to fully cover their Actuarially Determined Contributions each year. Normally, the full impact of variable ADECs falls on the employer (and thus the taxpayer), but a pioneering reform implemented in Arizona (with technical support from Reason) places some of the responsibility on employees. Sharing the burden of covering pension shortfalls between employers and employees logically extends the state’s new policy of restricting employer pickups.

Over the longer term, WRS can further lower the risk of accruing new unfunded pension liabilities by introducing optional defined contribution (DC) or cash balance retirement plans for new and current employees as an alternative to a traditional pension. As Rep. Burkart explained to me, higher wage earners at the University of Wyoming take advantage of a DC option. Maybe this can serve as a precedent for WRS.

By adopting lower assumed rates of return and increasing contribution rates, WRS and the legislature have taken important steps toward improving the sustainability of Wyoming’s public employee pension plans. Hopefully, state officials can build on these successes in future legislative sessions.