The killing of George Floyd and subsequent Black Lives Matter protests against police brutality across the country have sparked renewed conversation about racial inequities in the criminal justice system. In addition to disparities in the use of police force, mass incarceration disproportionately affects communities of color. Two driving forces behind the large prison population in the United States are high rates of recidivism and an ever-expanding number of laws and regulations that carry criminal penalties. Occupational licensing laws contribute to both these problems by hampering the reintegration of former offenders and criminalizing unlicensed entry into regulated occupations.

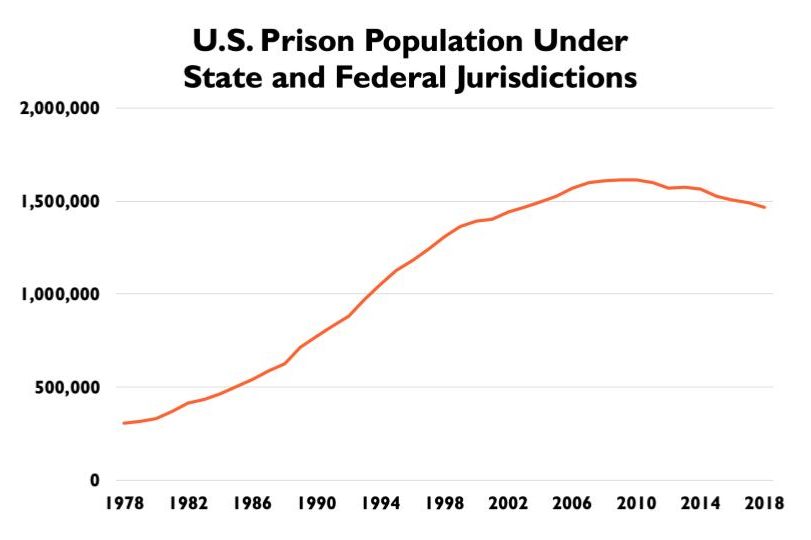

In the three decades between 1980 and 2010, the number of prisoners under state and federal jurisdictions increased by nearly 1.3 million. The most significant growth occurred during the 1980s and 1990s before leveling off throughout the 2000s. The prison population has slowly declined since 2009, but nearly 1.5 million people remain incarcerated in state and federal prisons each year. When jails, juvenile facilities, and immigration detention centers are included, that figure rises to 2.3 million.

Source: U.S. Bureau for Justice Statistics, National Prisoner Statistics Program

Black and Hispanic Americans are incarcerated at significantly higher rates than white Americans. According to a recent report from the U.S. Bureau for Justice Statistics, 1,134 out of every 100,000 black Americans were incarcerated in 2018. While the incarceration rate among black Americans dropped by 28 percent between 2008 and 2018, black males remain incarcerated at approximately 5.8 times the rate of white males. Racial disparities in incarceration rates are most dramatic among younger age groups. Black males between 18 and 19 years old are 12.7 times more likely to be incarcerated than their white peers.

One reason behind high incarceration rates in the U.S. is the rate at which prisoners return to prison after release. Another report from the Bureau for Justice Statistics found that 83 percent of prisoners released in 2005 were rearrested, or recidivated, in the nine years following their release. The vast majority of those who recidivated, 82 percent, did so within three years of release. The recidivism rate among black prisoners was 86.9 percent compared to 80.9 percent among white prisoners.

Prisoners whose most serious offense was property-related were among the most likely to be rearrested, suggesting that financial motivations play an important role in the return to criminal behavior. Moreover, much of the academic literature on recidivism suggests that access to gainful employment is a key factor for reintegrating former criminal offenders into society. A report from the U.S. Sentencing Commission found that recidivism rates were 20 percentage points lower among prisoners with stable employment compared to those who were unemployed. Among prisoners that do recidivate, those employed post-release go longer without re-arrest.

From a policy perspective, reforms that reduce barriers to employment for former offenders should be considered “low-hanging fruit” in the effort to reduce mass incarceration and the high rate of recidivism. One such barrier, occupational licensing, is particularly ripe for reform.

An occupational license is essentially a government-issued stamp of approval to enter into certain regulated occupations. In the 1950s, just five percent of workers required a license to do their job. Today, nearly one in four workers hold an occupational license. While licensing laws were originally intended to protect public health and safety, many licensed occupations present no such risk to consumers. For instance, state and local governments require licenses for a wide range of low-risk occupations like barbers, hair braiders, auctioneers, and tour guides.

Onerous licensing standards including minimum education requirements, mandatory training, and excessive fees are particularly burdensome for former criminal offenders looking to get back on their feet. To make matters worse, licensing laws in many states explicitly prohibit former offenders from obtaining licensure or include vague “moral character” requirements.

Several studies have linked occupational licensing laws to higher rates of recidivism. For example, a policy report from economist Steven Slivinski found that recidivism rates increased more rapidly in states with more burdensome licensing laws between 1997 and 2007. Recidivism rates increased most significantly in states that allowed licensing boards to deny licensure based solely on an applicant’s criminal history. These “prohibition states” experienced a 9.4 percent increase in recidivism rates compared to an average increase of 2.6 percent. Meanwhile, recidivism rates actually decreased by 4.2 percent in the least restrictive states.

Licensing laws not only raise barriers to reintegration, but they also contribute to the problem of overcriminalization. In fact, violation of licensing laws can result in heavy fees or even jail time. Moreover, two examples from Florida demonstrate how enforcement of licensing can result in wildly excessive use of police force.

In 2010, masked officers from the Orange County Sheriff’s Office wearing bullet-proof vests conducted SWAT-style raids of barbershops around the Orlando area. In total, 37 people were arrested in at least nine barbershops—most of whom charged with the crime “unlicensed barbering.” In reality, the raids were intended to find drugs or weapons but were conducted under the auspices of routine licensing inspections to avoid the need for search warrants. However, the raids only resulted in one arrest on felony drug and weapons charges. Another two arrests were for misdemeanor marijuana possession.

More recently, in 2019, the Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office carried out a sting operation to catch unlicensed handymen. Dubbed “Operation House Hunters” the sting resulted in 118 arrests, 110 of which were of first-time offenders. Most of the arrests were for “unlawful acts in the capacity of a contractor,” a misdemeanor offense punishable by up to $1,000 in fines and 12-months in jail. This sort of operation isn’t unique to Florida. Officers in California arrested 13 unlicensed contractors in a 2019 sting. Another sting in New York resulted in fines totaling $65,000.

Lawmakers should consider a number of licensing reforms. First, licensing requirements should be eliminated for occupations that pose no credible risk to consumers. Among licenses that cannot be eliminated, requirements should be minimized and focused on ensuring consumer safety.

Second, licensing boards should not be allowed to deny licensure based on applicants’ criminal records unless their prior offenses are directly related to the occupation in question.

Finally, enforcement of licensing laws should be left to state agency inspectors rather than armed police officers.

Of course, occupational licensing reform is only a small part of broader efforts to fix the broken criminal justice system. But eliminating unnecessary licensing requirements and reining in police authority to enforce licensing laws could help keep former offenders out of prison and reduce excessive uses of force.