As many state pension plans struggle with severe underfunding, the Wisconsin Retirement System (WRS) stands out with a funded ratio above 100 percent. Wisconsin’s fully-funded status can be attributed to a combination of plan design and pragmatism that ultimately enabled the system to swiftly regain full funding after past market declines.

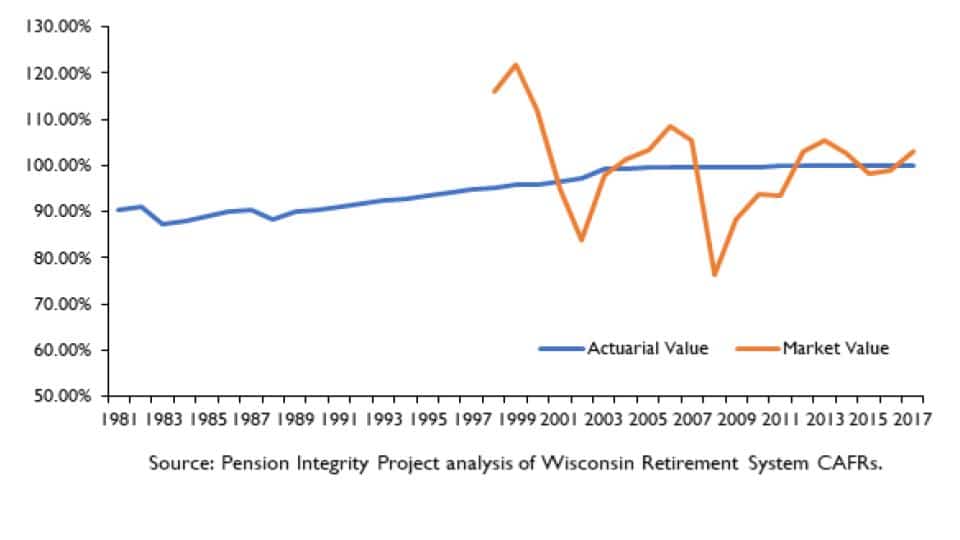

Wisconsin outranks all other states when it comes to pension funding. While national public pension plan funding averaged 72.1 percent in 2017, WRS reported a market value-based funded ratio of 102.9 percent and an actuarial value-based funded ratio of 100 percent. This wasn’t something that happened by chance, but rather through a series of careful considerations and thoughtful, timely reforms.

Figure 1: Wisconsin Retirement System Funded Ratio

Wisconsin’s experience with public retirement systems began with the creation of the Milwaukee Police Pension Plan and the Milwaukee Fire Pension Plan in 1891. Over the next 50 years, the state and many local governments followed suit. By the mid-1940s, Wisconsin had a myriad of pension systems covering a wide variety of state and municipal employees. Recognizing that some of these plans were “defective in structure” and “glaringly unsound,” the state legislature created a Joint Legislative Interim Committee on Pensions and Retirement Plans to study its public employee retirement landscape.

Committee members were concerned with problems of coordination and financial sustainability that a large number of systems across the state posed, along with early retirement incentives provided by some plans. And, in 1947, the committee reported back with goals and recommendations for the sustainability of the retirement systems. After saying the state’s array of pension plans at the time were as “bewildering as Alice in Wonderland,” the committee recommended merging most of the current systems. Most local plans were closed to new participants who were instead placed in the Wisconsin Retirement Fund. The only exemptions were the separate city and county of Milwaukee employee pension funds and the various teacher pension funds.

In order to ensure effective plan management and design, the committee examined previous pension plans to identify where they had fallen short. In these deficient plans, the committee discovered a commonality: objective actuarial information was not available. Instead, actuarial calculations were supplied by lobbyists or department heads. Thus, in addition to recommending the use of trained actuaries, the committee advised using conservative mortality and return assumptions.

The trend toward consolidation continued in 1975, when the Wisconsin Retirement Fund, the State Teachers Retirement System, and the Milwaukee Teachers Retirement Fund merged into the Wisconsin Retirement System. Police and fire pension funds, excluding Milwaukee, also consolidated into the WRS in 1977.

This merger provided a foundation vital for the WRS solvency that is seen today. At retirement, participants will receive an annuity from one of two plans—a formula-based benefit (a defined-benefit pension plan) or a money purchase benefit (a defined-contribution plan)—and the calculation that offers the highest annuity will be the one the participant receives. The formula-based benefit favors long-term employees, while the portability of the money purchase benefit serves the interest of shorter-term employees.

In 2015, about 74 percent of retirees received the formula-based pension benefit. Included in the plan are the Core (formerly known as “Fixed” until 2005) and Variable funds, where pension contributions are invested. Participants are able to place all of their contributions in the Core Fund or choose to put a portion in the Variable Fund, where the portfolio consists of common stocks and offers a possibility of higher returns but with more uncertainty.

Instead of making potentially unsustainable promises in the form of fixed-rate annual cost-of-living increases untethered to actual changes in consumer prices, the system allows adjustments to annuities based on investment outcomes and the funding needs of the plan. For participants, this means they will usually see higher benefits in bull-market years but when the market declines, any increase to their pension benefit may be reduced or skipped. These modifications to pension benefits based on investment performance allow plan administrators to maintain WRS funding in bear market years without placing overwhelming fiscal pressure on taxpayers. In addition to this risk-sharing method, the plan requires employers to fully pay the actuarially determined contribution, preventing the payment shortfalls that have put the pension systems of other states, like Illinois and New Jersey, at risk.

Although structurally sound today, and widely regarded as a leader in resilient pension plan design, like all pension plans WRS faces political and market risks that require vigilance to maintain solvency. For example, Act 11 of 1999 increased fiscal pressure on the system through benefit enhancements. The measure increased formula benefit multipliers, maximum formula benefit payables, and death benefits for some participants. The market-value based funded ratio dropped during this time period, falling from over 100 percent prior to the 1999 Act to 83.9 percent in 2002 (a stock market decline during this time also contributed to the funding decline).

In 2011, the Wisconsin legislature passed and then-Gov. Scott Walker signed a reform package that included measures designed to improve pension sustainability. As an attempt to balance the state budget after a large deficit, Act 10 introduced pension cost- and risk-sharing measures that remain in effect today:

- General-status and elected-status WRS participants are required to contribute half of all actuarially required contributions. Protective-status (public safety) employees are responsible for the same contribution rate as general-status participants, with employers covering the remainder of the required contribution.

- WRS employers are prohibited from taking over portions of required contributions for participating employees (so-called “pick-ups”), with exemptions for public safety employees utilizing collective bargaining agreements with those conditions.

- The pension benefit formula for executive-status employees—including the governor, members of the state legislature and unclassified executives—was reduced to 1.6 percent from 2 percent to match the existing rate for general-status employees.

- Those hired into public employment on or after July 1, 2011, are subject to a five-year vesting requirement, requiring a minimum of five years of creditable service to be eligible to receive a WRS benefit.

Combining these cost-sharing methods with full annual actuarially determined contributions into the system has reduced financial risk while helping restore system solvency.

That same year, Act 32 modified Act 10 by prohibiting municipal employers of police and fire employees and state employers of troopers and vehicle inspectors from utilizing pick-ups, reinforcing shared responsibility of employers and employees.

These policies relieve pressure on taxpayers and promote a shared sense of responsibility to maintain solvency. Failing to immediately address the losses caused by the Great Recession of the late 2000s and early 2010s could have prompted growing pension debt. Instead, the reforms Wisconsin enacted ensured healthy pension funding and prudent risk-sharing policies going forward.

With the exception of Milwaukee, public employee participation in WRS is mandatory—generating a system with 632,802 participants with a median annual pension benefit of $20,758. While this benefit may seem low, the average WRS participant retires with only 21 years of service. In addition, living costs in Wisconsin are low, especially for retirees. These modest pensions allow for the sustainability of the system and retirees in the state to continue at their current standard of living.

Plan designs that include flexible cost-sharing methods are gaining interest—like recent reforms in Michigan, Arizona, and Colorado, for example—compared to traditional defined-benefit plans, in part because of the ability to better manage risk. When pension systems allow adjustments in costs and/or benefits based on fluctuations in investment returns or other factors affecting funding status, the plan protects promised pensions by ensuring full funding. Employer and employee cost-sharing can also ease the burden that unexpected costs can pose on state and local budgets, as well as balance the responsibility between the taxpayers and employees. Another benefit comes from the policy to make full actuarially required annual payments—a policy not exclusive to, but common with, cost-sharing plans.

Overall, the Wisconsin Retirement System is in good shape. Consolidating the previous systems, embracing prudent reforms, and utilizing sound actuarial assumptions is working in its favor. The cost- and risk-sharing aspects of the system have been instrumental in securing Wisconsin retirees their pension checks. Most other state and municipal pension systems, including the pension systems in Milwaukee, could learn from Wisconsin’s blueprint and success.

Stay in Touch with Our Pension Experts

Reason Foundation’s Pension Integrity Project has helped policymakers in states like Arizona, Colorado, Michigan, and Montana implement substantive pension reforms. Our monthly newsletter highlights the latest actuarial analysis and policy insights from our team.