The Federal Trade Commission and 17 state attorneys general filed a wide-ranging antitrust suit against Amazon late last month, beginning a process that may end in one of the most consequential antitrust cases in U.S. history. Amazon’s size and central role in the shift to e-commerce would be enough to confer such importance on the case, but its outcome may also dramatically impact U.S. competition policy itself.

The case against Amazon is built on the premise that the firm “has seized control over much of the online retail economy.” However, the FTC takes an inappropriately narrow view of the competition Amazon faces from other retailers who use the online and brick-and-mortar channels in a wide variety of ways. In doing so, the FTC overstates Amazon’s already large share of online retail and ignores the central innovative role of Amazon in how these markets evolved.

The FTC’s complaint makes numerous and wide-ranging allegations against Amazon of anticompetitive conduct. Amazon’s Prime subscription service, order fulfillment, use of pricing algorithms, and advertising on its website all figure prominently in the document. There is still much to learn about the specifics of these allegations- the complaint’s contents are heavily redacted- and the evidence presented by both sides as the case moves forward.

These alleged bad acts form an “interconnected strategy to block off every major avenue of competition—including price, product selection, quality, and innovation—in the relevant markets for online superstores and online marketplace services.” This definition of markets neatly splits Amazon into its two major retail businesses, first-party retail, and Amazon Marketplace, where third-party sellers pay fees for using Amazon’s platform and other services.

Amazon’s large first-party retail customer base makes the platform more valuable to Marketplace sellers, who, in turn, attract even more buyers to the site. The complaint continues:

The biggest threat to Amazon’s monopoly power would be for a rival to attract its own critical mass of dedicated customers. Competitors able to build a sizable base of either shoppers or sellers could spin up their own “flywheels,” overcome barriers to entry and expansion, and achieve the scale needed to compete effectively in the relevant markets.

The complaint’s key assumption is that for meaningful competition to occur in online retail, more firms must gain a “critical mass” of customers in one or both markets as the FTC has defined them. The FTC directly names only two competitors in the market for “online superstores,” Walmart and Target, and two in the market for “online marketplace services,” Walmart and eBay. Amazon’s first- and third-party sales online are far higher than the named competitors, allowing the FTC to portray Amazon’s market share in excess of 70 percent, not enough to justify talking points that abuse the term “monopoly,” but nonetheless very large.

To justify its definition of relevant markets, the FTC attempts to establish that other first-party retailers—brick-and-mortar stores and more specialized online retailers—do not provide options to customers that adequately substitute for those of online superstores. Similarly, it seeks to show that third-party sellers have no meaningful alternatives to online marketplace platforms.

Market definition is a contentious topic in almost all antitrust cases and is often argued in the courtroom through statistical analysis by economic experts. Because most products and services in the modern economy are naturally differentiated, identifying how closely products or services outside the definition of the market in question are substitutable comes with a degree of subjectivity.

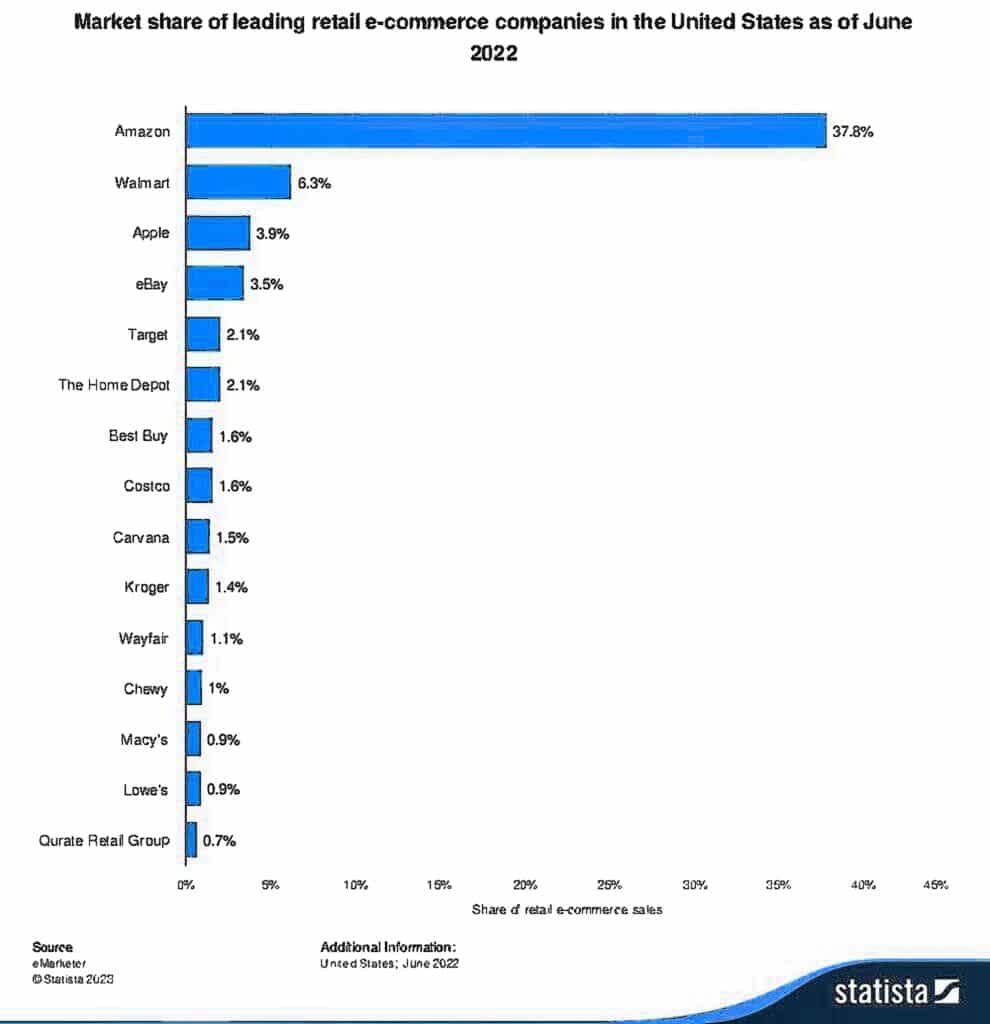

The figure below shows the 15 largest U.S. retail websites in 2022. This list is not an alternative definition of relevant markets but is a useful tool in stress-testing the FTC’s assumptions underlying the narrow markets it considers relevant.

Amazon is the largest online retailer in the United States by any measure, with its website accounting for almost 38 percent of sales. There are also no other firms in the top 15 that neatly conform to the FTC’s understanding of either an online superstore or marketplace beyond the three named in the complaint. However, the list demonstrates immediate flaws in the FTC’s reasoning that meaningful competition can only come with substantial growth from more firms in these narrow categories.

There is striking diversity among the top 15 U.S. e-commerce sites in current product offerings, business models, and the historical path each took to e-commerce. Many of the top 15 were (and remain) primarily brick-and-mortar retailers who leveraged those operations or brand loyalty to attract consumers online. Others are internet-era startups, like Wayfair, who have leveraged their online success to make inroads in the brick-and-mortar market.

The FTC’s analysis supporting the claim that more specialized online retailers do not belong in Amazon’s relevant market is very thin. We are told that “online superstores provide shoppers a unique offering: 24/7 access to a broad and deep product selection accompanied by a distinct set of features that meaningfully reduce the time and effort shoppers expend online. These features include tools to help shoppers quickly search for and identify their desired items, compare different items, and purchase and receive items, all from a single website or app.”

One-stop shops with familiar user interfaces are indeed an asset in e-commerce, though the convenience factor emphasized by the FTC was almost certainly more relevant when retail was largely confined to brick-and-mortar channels. Today, people are comfortable keeping dozens of tabs open in their web browsers and have grown increasingly comfortable navigating checkout on e-commerce sites. “Traveling” between online retailers involves a few clicks and takes a small fraction of the time most consumers need to drive between physical stores.

Oddly, when the FTC gets around to arguing brick-and-mortar retailers are not within the relevant markets, it sidelines this logic, leading instead with the observation that, “Online superstores allow shoppers to browse and buy across a wide variety of goods 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year.” The FTC once again identifies a differentiating factor, but one that common sense suggests falls short of fully delineating a relevant market.

E-commerce has reshuffled the retail deck, meaning firms compete in many ways across many markets. The FTC, for example, explicitly rejects that Amazon and specialty online retailers like Home Depot compete in the same relevant market. But as of 2022, Home Depot’s share of sales in the home-improvement market across all channels is above 30 percent, with Amazon coming in second at around 25 percent. Analysts consider home improvement a market conducive to leveraging a large chain of brick-and-mortar stores to the online channel. The advent of e-commerce requires us to look at competition from many angles.

E-commerce has also created ways for large specialized retailers, smaller firms, and sellers to use market platforms to reap some of the benefits of scale and network effects without being a one-stop shop with a critical mass of customers. For example, many retailers (both large and small) use PayPal, which commanded 41 percent of the online payments market in 2022 (Amazon’s own payment system is a distant fourth). Familiar payment systems allow even small independent sellers to provide trust and security online.

Online retailers, market platforms, and other tech companies continue to spawn new ways to compete without Amazon’s critical mass. Shopping apps and the shopping tab now offered by search engines like Google enable rapid comparison of prices and offerings across sites, further reducing the FTC’s cited advantages of one-stop-shop superstores.

In the context of a technology boom still underway and still subject to radical uncertainty, the FTC’s rigid and narrow definition of markets is even more fundamentally flawed. The FTC appears to view the lack of several other firms successfully employing business models nearly identical to Amazon as evidence of the company’s monopolization and anticompetitive conduct through time. However, Amazon’s business model developed over time as a process of entrepreneurial experimentation. It did not enter and monopolize the “online superstore” and “marketplace services.” markets. In large part, it invented those markets.

At its founding in the mid-1990s, Amazon was a venture similar to the specialty retailers the FTC excludes from its analysis today. The online bookseller quickly added compact discs, other media, and many more products in the late 90s. In 1999, the company launched zShops, where individuals and small businesses could sell used items. zShops evolved into Amazon Marketplace. Amazon began to offer the fulfillment services at issue in the FTC suit in 2005, and its marketplace platform became an increasingly appealing channel to other retailers rather than individual sellers.

Amazon made these decisions as the internet was gaining widespread adoption and amid uncertainty about whether consumers would make retail transactions online. It was famously unprofitable for its first decade.

While Amazon entered the 21st century amid operating losses and skepticism of its business model, Walmart was the world’s leading retailer and occupied a place in the public debate remarkably similar to Amazon’s today. Low prices for consumers, driven by scale and cutting-edge logistics, were often framed as a Faustian bargain, allowing the retail giant to dominate local markets and engage in unfair labor practices.

Walmart remains a retail giant today. While a distant second to Amazon online, sales in its physical stores are high enough to keep it just ahead of Amazon in total U.S. retail sales. Walmart did not aggressively pursue growth online until a series of acquisitions in 2017. The firm’s massive brick-and-mortar customer base and logistics have helped it make significant inroads in online retail in a relatively short time.

Walmart’s sales online (and its newer but fast-growing marketplace) are a distant second to Amazon’s, but there is no indication Walmart’s competitive strategy includes developing online operations at a “critical mass” like Amazon. Assuming otherwise would make no more sense than assuming Walmart’s monopolization of the brick-and-mortar retail superstore market prevented thousands of competing Amazon physical superstores from opening. It is nonetheless safe to assume Amazon and Walmart, with different approaches, will vigorously compete in the coming years.

Target and eBay have also taken unique paths to the top of the U.S. online retail market and have their own unique capabilities. This type of dynamic competition and entrepreneurship is certainly not new in the internet era, but the revolution in information and network technology still underway has both sped up the process of innovation and made it a more central part of what robust competition means.

FTC Chair Lina Khan often argues antitrust has failed to keep up with the times, particularly on big tech. But the narrow and rigid definition of online retail markets on which the FTC builds its case against Amazon is even more out of step with a high-tech economy.