Nationwide, a significant portion of jail and prison inmates suffer from mental illness. In many cases, these individuals cycle in and out of the criminal justice system without receiving appropriate care and consideration for their particular needs. Consequently, people with mental illnesses are more likely to re-offend, re-enter the criminal justice system, and have violent encounters with law enforcement. The status quo is failing people struggling with mental illness and it also results in reduced public safety and wasted taxpayer dollars.

However, some states and municipalities are implementing interventions within courts, the community, and correctional institutions that could help address this shortcoming of the criminal justice system and serve as models for others to follow.

A 2006 report from the U.S. Bureau for Justice Statistics found that more than half of all inmates in prisons and jails had a mental health problem. Mental health problems were most prevalent within local jails (64% of inmates), followed by state prisons (56% of inmates) and federal prisons (45% of inmates). The incidence of mental health problems remained high, even when only considering relatively severe disorders.

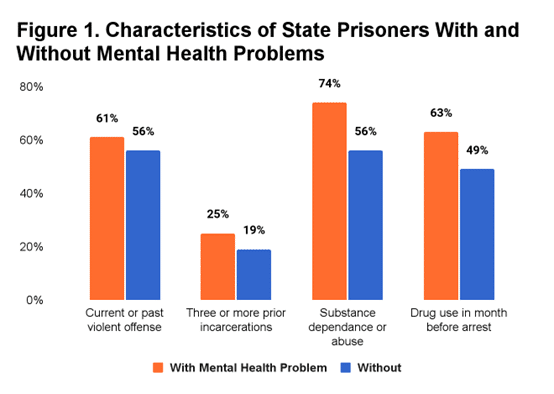

According to the report, an “estimated 15% of state prisoners and 24% of jail inmates reported symptoms that met the criteria for a psychotic disorder.” Inmates with mental health problems were found to be more likely to have committed violent offenses, have more prior offenses, have substance abuse disorders, and have used drugs in the month prior to their arrest (Figure 1).

The prevalence of mental health conditions among inmates suggests that treatment and alternative interventions may be valuable in terms of rehabilitation and reducing the risk of future offenses.

One alternative intervention is the use of mental health courts (MHCs), which are specialized court systems that serve as diversion tools to keep individuals with mental illnesses out of the traditional criminal justice system. These courts were developed to address the inability of traditional correctional institutions to rehabilitate offenders with mental illness. They are designed to redirect offenders who would normally be sentenced to incarceration into mandated treatment.

Mental health courts service individuals who are charged with a variety of offenses but the majority of cases usually involve misdemeanors. Although foundationally similar, MHCs are developed individually and are based on the needs, regulations, and treatment availability of their jurisdiction. For this reason, there is no single MHC model. However, MHCs typically rely on a team of court staff and mental health professionals to design treatment plans unique to each defendant that participates in the court process.

Over time, mental health courts could potentially save public funds by reducing recidivism. For example, an analysis of MHC outcomes in North Carolina found that individuals who completed the mental health court process were 88% less likely to be re-arrested than those who did not. Using administrative data from county and state agencies, a 2007 Rand study suggested mental health courts could result in long-term net savings to the government due to reduced recidivism and reductions in relatively expensive types of mental health treatment such as hospitalization.

When individuals with mental illness re-enter the community under supervision programs such as parole or probation, their particular needs should also be accounted for through specialized programs. Specialized supervision programs target common challenges facing individuals with mental health needs that lead to rearrests. In contrast to traditional parole and probation officers, officers with specialized cases need to be knowledgeable about the mental health needs of their probationers. This is important because they serve as their point of contact with judges, attorneys, psychiatrists, and many others.

In an Illinois study, 40% of program participants had no new arrests or offenses within three years after their probation was terminated. Study participants received individualized case management aiding in meeting needs such as housing, food, and employment in addition to receiving mental health assessment, treatment, and counseling.

A more recent 2017 study found that after two years, 29% of specialty probationers were rearrested in comparison to 52% of probationers who participated in the traditional probation process. The success of these programs shows that planned programmatic improvements and partnerships can have a positive effect on lowering the recidivism rates of mentally ill offenders.

For those who are not diverted from traditional correctional institutions, it is essential that their mental health needs be prioritized while they are incarcerated. Offenders within the correctional system should be quickly identified and provided with treatment to assist their rehabilitation and avoid exacerbation of their mental illness.

In 2014, the Federal Bureau of Prisons released a program statement with policies, procedures, and guidelines for the implementation of mental health services for inmates with mental illness within correctional institutions.

A 2016 meta-analysis by the National Institute of Justice’s CrimeSolutions found that if treated while incarcerated, adult offenders within their study were significantly less likely to commit crimes when compared to adult offenders who did not receive the same treatment.

Of course, policymakers should pursue reforms that would expand access to treatment and prevent individuals from entering the criminal justice system in the first place. But once an individual has entered the justice system, the priority should be to ensure that they receive the care they need to not commit further crimes in the future. The traditional justice system fails to meet the needs of mentally ill offenders, resulting in high recidivism rates among offenders with mental illness. The formation of mental health courts, prioritization of treatment within correctional settings, and specialized community supervision programs are promising interventions that could improve public safety and save tax dollars by slowing the revolving door of mentally ill offenders cycling in and out of the criminal justice system.