Near the close of the 2021 session, the Texas Legislature took a major step to strengthen the state’s fiscal future when it passed a major reform to the pension plan serving most state government employees—the Employees Retirement System (ERS). The pension reform bill is designed to tackle persistent structural underfunding and pay down over $14 billion in unfunded liabilities.

The reform—Senate Bill 321 (SB 321)—was the result of a bipartisan, collaborative effort to addresses many of the major challenges facing the Employees Retirement System. The law, signed by Texas Gov. Greg Abbott on June 18, includes two major changes: committing the state to make annual contributions that will fully fund the retirement promises already made to public workers and introducing a cash balance plan for future hires that will manage any further unexpected costs to taxpayers.

We’re proud to say the Pension Integrity Project at Reason Foundation played a key role in the collaborative effort that drove this successful ERS reform, providing technical assistance, policy analysis, and educational outreach on ERS reform to a wide range of policymakers and stakeholders throughout the reform process, including bill sponsor State Sen. Joan Huffman and many individual legislators. Dating back to 2020, we provided independent actuarial modeling related to ERS reform concepts and offered advice on design concepts and fiscal implications to legislative leaders, governmental stakeholders, and a diverse array of non-governmental partners including the Texas Public Employees Association, Department of Public Safety Officers Association, Texas 2036, Americans for Tax Reform, Americans for Prosperity-Texas, Equable Institute, and Texas Public Policy Foundation.

With Senate Bill 321 signed into law, Texas joins the growing list of states taking bold action to tackle persistent public pension underfunding in recent years, including Michigan, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Pennsylvania, and others.

However, in true “everything’s bigger in Texas” form, the Lone Star State deserves special acknowledgment for doing what few states have yet been able to do—embrace, in one legislative package, a comprehensive reform effort that both offers a realistic policy to fully pay off all current unfunded liabilities while simultaneously modernizing the retirement benefit for new hires to avoid new unfunded liabilities and still ensure strong, guaranteed retirement security for future state workers. The holistic nature of Texas’ approach should serve as a model for structural pension reforms in other states facing similar underfunding challenges.

1. The Problems

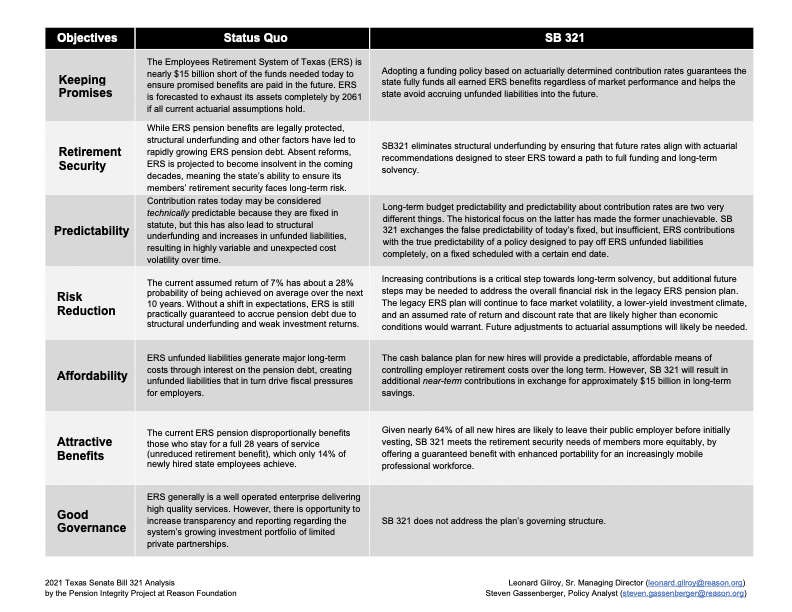

Over the last two decades, the Employees Retirement System—which provides retirement benefits to most state public employees and sworn law enforcement personnel—has gone from fully funded to holding $14.7 billion in unfunded pension obligations. ERS was, prior to Senate Bill 321, trending toward complete insolvency over the next 20 to 30 years—absent significant legislative changes.

Figure 1: History of ERS Solvency (2001-2020)

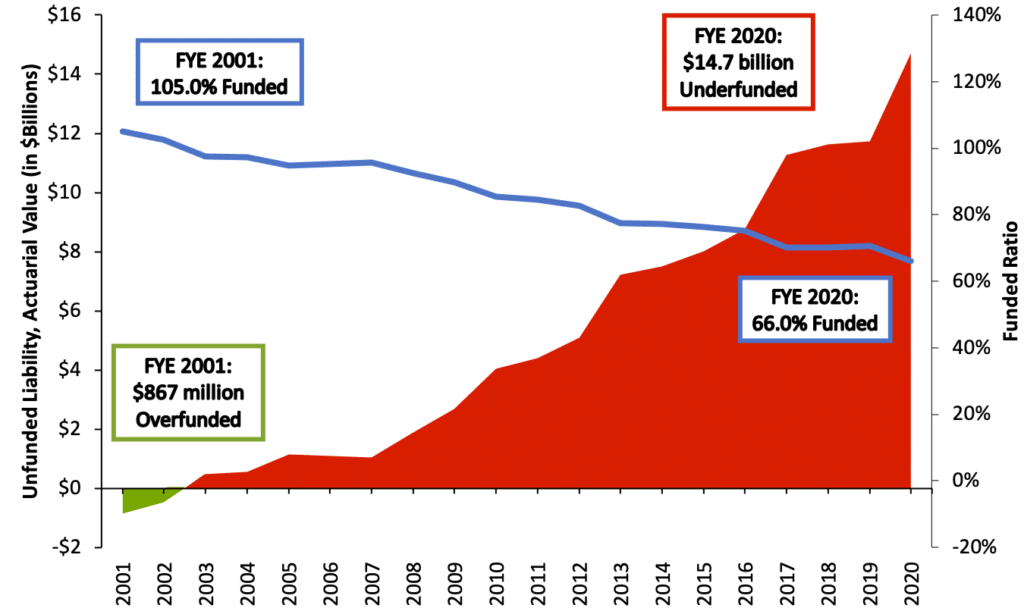

There are several reasons for these growing unfunded liabilities. According to ERS reports, over $8 billion in pension debt is the result of overly optimistic investment return assumptions and investment returns underperforming what plan actuaries expected. Another $4.5 billion of this debt is the result of the state government systematically underfunding its public pension systems.

Figure 2: Causes of ERS Pension Debt (2001-2020)

The current reform effort comes after years of warnings from ERS administrators and actuaries that the pension system would never reach full funding if nothing dramatic changes, nor will the current funding method—based on legislatively chosen (not actuarially determined) contribution rates that are too low and structurally underfunding the ERS system—ever pay down the $14.7 billion pension debt.

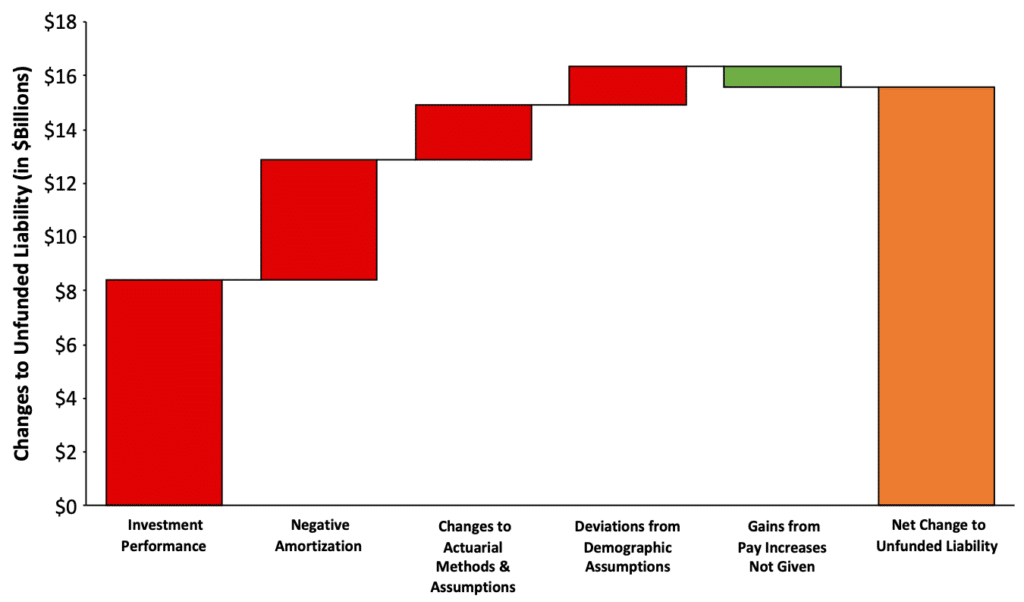

Worse, this structural underfunding is happening despite the fact that relatively few Texas workers—less than 14 percent of those hired under age 35 by the state—actually work long enough to receive a full unreduced retirement benefit. A whopping 64 percent of Texas state workers work for the government for less than five years, the point of “initial vesting” at which they would start to be eligible to tap some portion of the employer contributions made on their behalf if they left state service.

Figure 3: Probability of Members Remaining in ERS (Hired at Age 25)

In short, Texas has been structurally underfunding a retirement plan designed to address the needs of a small cohort of public employees. Public pension costs and debt continue to rise rapidly even though benefits haven’t changed.

2. The Reform: Summary of Senate Bill 321

Senate Bill 321 provides a holistic solution to the challenges associated with ERS using two distinct and complementary approaches:

- First, SB 321 addresses the source of runaway costs by reforming the design of the retirement plan for new workers through a new cash balance plan that will, over the long run, lower taxpayer financial risk with every single new hire.

- Second, it addresses funding and contribution policies to clean up two decades worth of structural underfunding that drove billions in unfunded liability accrual. The reform originally approached this second part with a proposed supplemental employer payment but was prudently amended in the Senate to instead adopt an actuarially determined contribution policy.

What Is a Cash Balance Plan?

A standard cash balance plan design blends positive attributes of both traditional pensions and more portable defined contribution plan designs into a unique type of retirement benefit that, like a pension, offers some guaranteed lifetime income to employees, but, like a defined contribution plan, does so in a framework designed to minimize taxpayer cost and risk.

Cash balance plans provide members with their own individual retirement accounts within which they contribute a portion of their salary along with their employer, who adds an additional predetermined matching interest credit. Texas’ new cash balance plan will have employees contribute 6 percent of their pay into their accounts, and employers will add an amount equal to 9 percent of pay.

The funds of law enforcement and corrections officers—who have earlier retirement and thus need larger annual contributions—will get an additional 2 percent from employees and 6 percent from employers.

A cash balance plan defines a member’s benefit as a constantly growing account balance. In this case, ERS will have a 4 percent minimum annual investment return rate. The plan also takes any market earnings between 4 percent and 7 percent and splits it evenly between both parties; any investment returns exceeding 7 percent would be retained by the cash balance plan to offset potential future year losses.

A traditional pension plan like the legacy ERS benefit defines a member’s benefit using an accrual formula based on salary and years of service. Table 1 below shows how Texas’ new cash balance plan will credit a member’s account each year with a “pay credit” (percent of pay) and a guaranteed return “interest credit rate.”

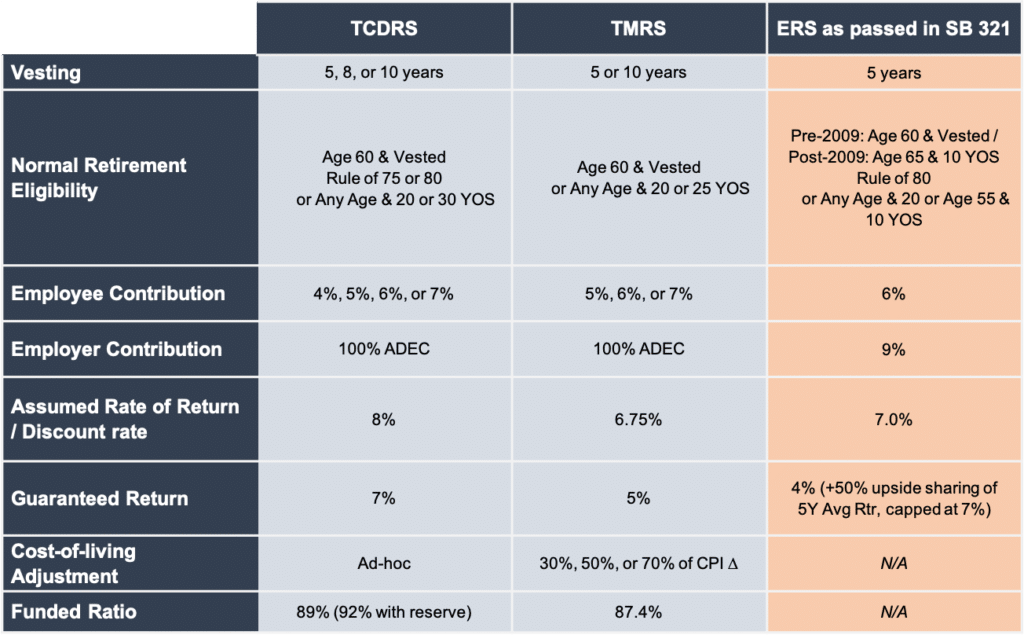

The decision to establish a cash balance retirement plan to new hires leans heavily on the experience of municipal governments in Texas, many of which rely on one of two large cash balance plans—the Texas Municipal Retirement System and the Texas County and District Retirement System—which have offered a guaranteed return to members on a fiscally sustainable basis for employers despite decades of market volatility. Table 1 provides a comparison of the major benefit provisions of these two systems relative to the new ERS benefit under SB321.

Table 1: Comparing ERS’ New Cash Balance Plan to Texas’ County and Municipal Cash Balance Plans

Cash balance plans have several advantages over traditional pensions, both for employees and employers. For the new ERS members who will be enrolled in the cash balance plan, they will enjoy a more portable and flexible retirement fund, which can move with them as they transition to other employment options. They will also enjoy a 4 percent return guarantee, which places a floor on annual earnings their account will accrue, but at a much more achievable and realistic level than the 7 percent return guaranteed by the legacy ERS pension system.

For employers, the cash balance plan places limits on unexpected long-term costs. Instead of having to cover any returns below the Employees Retirement System’s 7 percent assumed rate of return, the state will only be obligated to pay for any returns below the guaranteed 4 percent. And retaining a portion of returns above the 4 percent guaranteed rate will help the system fund future market downturns. All in all, the new cash balance plan means a much lower level of long-term financial risk for the state.

What Is Actuarially Determined Pension Contribution Policy?

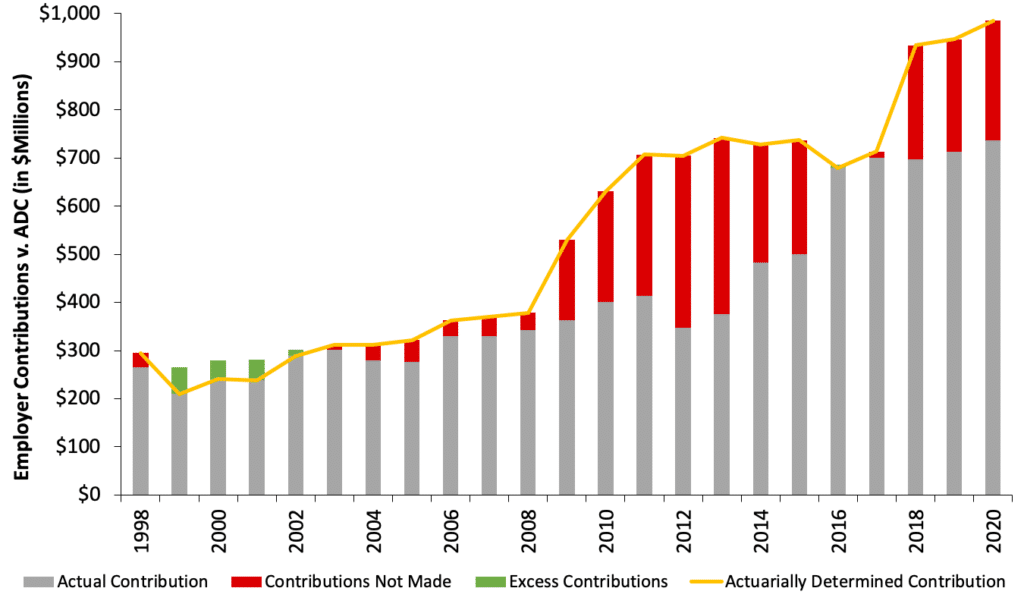

Historically, the Texas legislature has set its own annual contributions with no deference to the actual funding needs expressed by ERS actuaries. Adding another layer of complexity to the issue, Texas has had a constitutional limit on how much they are allowed to pay into their public pension plans. The result of these policies was an inflexible annual contribution to the pension funds, and as the actual costs of funding promised benefits rose, state contributions were systemically underfunding these benefits (see Figure 4). Since these benefits must eventually be paid, and funding shortfalls mean less money to accrue annual market returns, this structural underfunding has come at a tremendous cost to the taxpayer.

Using actuarially determined employer contribution (ADEC) policy will mean that the state is essentially committing to fully fund pension obligations. The actual costs of funding a defined benefit retirement plan can vary significantly from year to year depending on how accurately a plan predicts market, demographic, and payroll trends. Every year a plan’s actuary calculates how much money is needed today to eventually provide an earned benefit.

Figure 4: ERS Statutory vs. ADEC Contributions (1998-2020)

With the implementation of SB 321, the state will shed its failing statutory contribution policy and begin making annual payments based on ADEC requirements. That will mean higher, but now sufficient, payments into the ERS fund to fully fund pension promises made to Texas workers over a 30 year period. Instead of an annual, fixed contribution of 10 percent of the state’s total payroll—a policy that has created significant unfunded liabilities for the state—the state will be making more dynamic payments that adjust according to experience.

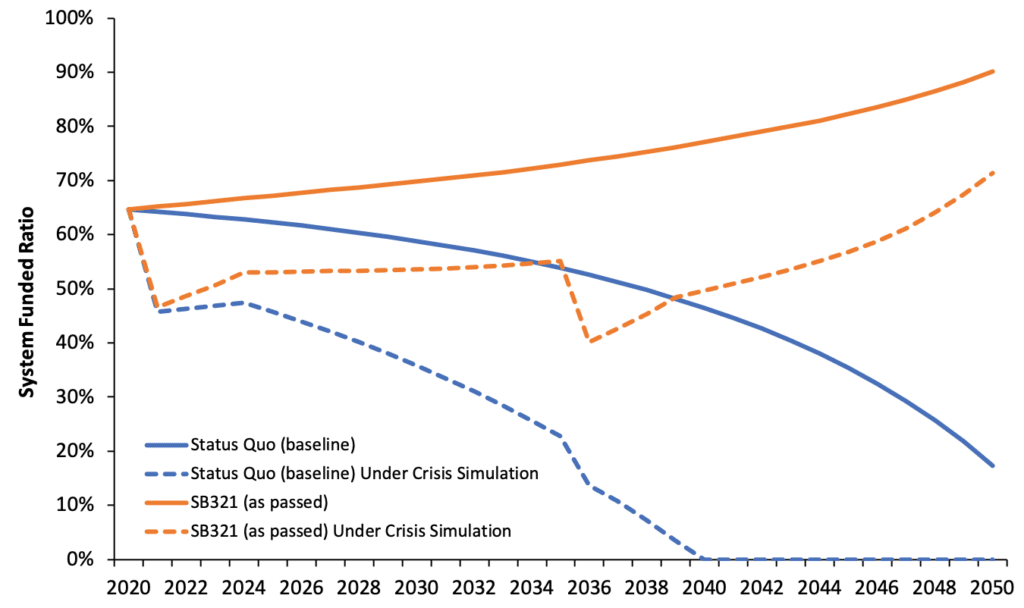

The result of this policy adjustment makes a marked difference in the outlook of ERS over the next 30 years, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Comparing ERS Funding Forecasts (Status Quo vs. SB 321)

Switching to an actuarially determined employer contribution policy makes an unmistakable difference in the outlook of the ERS’ fiscal future and completely changes the financial trajectory, for the better. Whereas the plan was on an unsustainable path before (deteriorating funding and insolvency within a few decades), the increased contributions from SB321 would reverse the decline in the plan’s funding and ensure that ERS nears full funding within the projected 30-year timeframe.

Using an ADEC policy will also improve the plan’s ability to navigate continued market volatility. To apply stress testing to the system’s funding, we apply a “crisis simulation” to ERS, which uses 6 percent year-to-year returns and 2008-like recessions in 2021 and 2036. Before the reform, ERS responded very poorly to the introduced market stress, seeing major drops in funding levels and complete insolvency within 20 years. With the introduction of an ADEC contribution policy, ERS funding will continue to trend up, even applying crisis simulations.

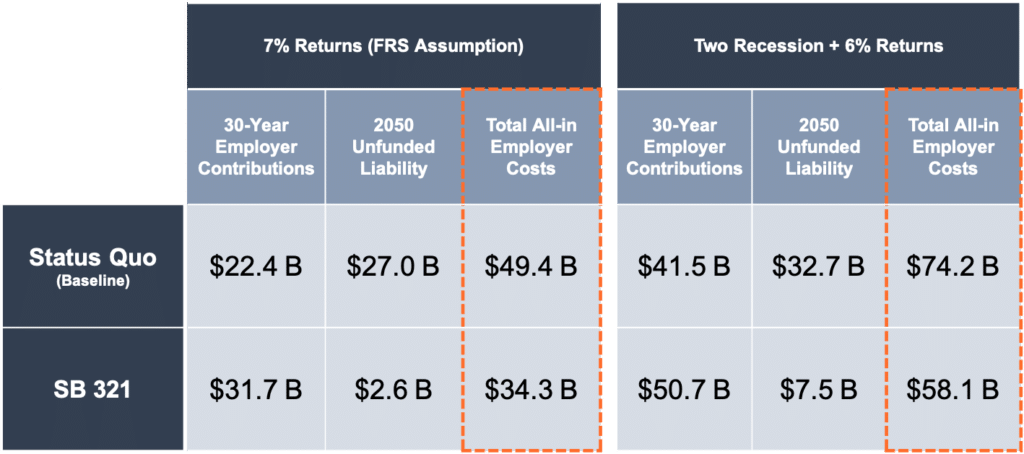

3. Long-Term Cost Impact of SB 321

Initial analysis suggests that this change in contribution policy could mean annual contributions at least 6 percent higher than current rates, but ensuring the pension benefits are fully funded will mean significantly reduced costs in the long term. Pension Integrity Project actuarial modeling of Texas Senate Bill 321 shows that instead of a worsening funding trend, SB 321 would ensure that the Employees Retirement System ends up with an improved funding result while driving net savings of at least $15 billion in taxpayer costs over the next 30 years (see Table 2).

Essentially, the reform ensures that Texas taxpayers aren’t paying $20-$40 billion into the legacy ERS fund over the next 30 years and ending up in an even worse fiscal position, despite that sacrifice.

Table 2: Long-Term Costs (Status Quo vs. SB 321)

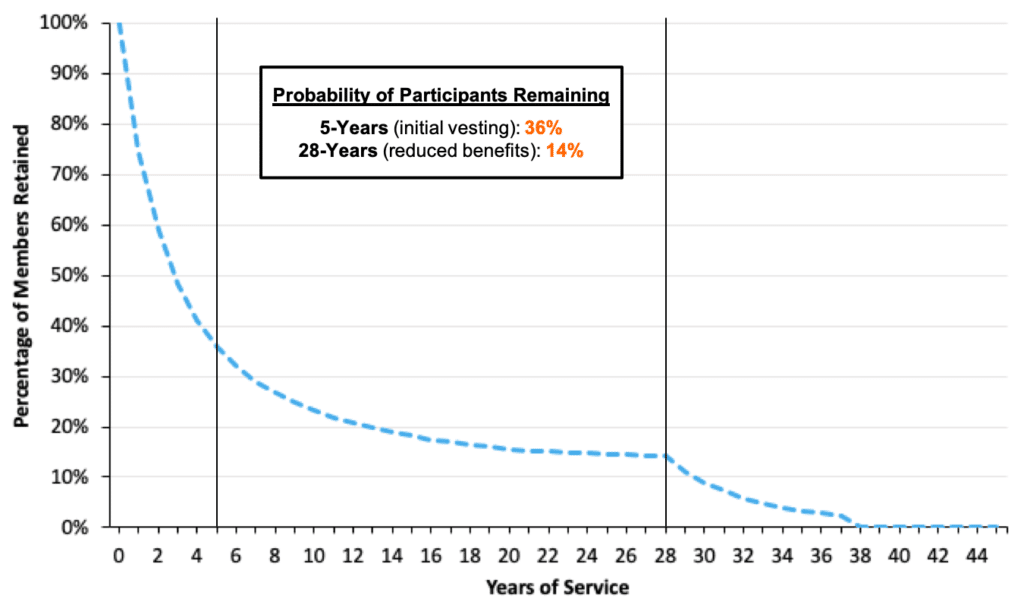

4. Grading SB 321

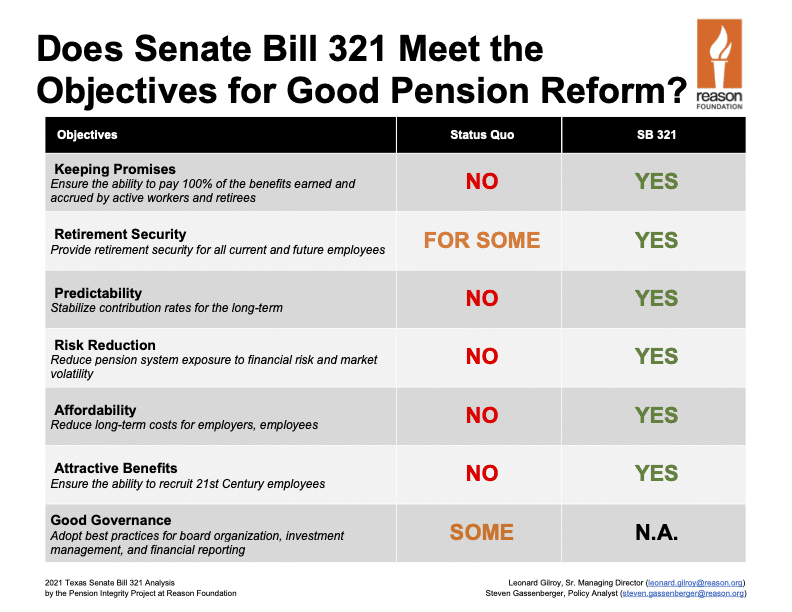

The Pension Integrity Project uses a rubric of seven objectives of good pension reform to evaluate bills. Our grading shows that Texas Senate Bill 321 represents significant improvements in nearly all facets of effective reform, including a better plan to keep promises made to public workers, improved retirement security, more predictability in future contributions, reduction of risk to the state, reducing long-term costs, and adding benefits that are attractive to a wider group of new members.

5. Reviewing the Process

The road to passage of Senate Bill 321 involved collaboration between many different interest groups and policymakers, which generally fostered an inclusive reform process with representation from all relevant stakeholders. This setting ensured a final product that works for everyone involved, which greatly improved the chances for success in the end.

That is not to say the process was without its challenges. After the bill’s passage in the Senate, the House of Representatives added a small, but ill-advised, technical amendment to the bill that was more of a hindrance than an improvement. In an attempt to allow long-tenured public employees to keep working longer, the amendment gives ERS members who are over age 60 and who have worked for their public employer for over 30 years the ability to stop accumulating and begin drawing on their public pension early—without actually retiring. The ill-advised amendment is expected to only impact about 35 of the most senior ERS members, according to the bill’s House sponsor, but those members include a handful of long-standing legislators.

Actuarially, the House amendment made no discernable difference to the funding or cost of ERS, but the legislative preferential treatment for certain members prompted understandable questions in the Senate and only hindered the bill’s ability to succeed. Based on that assessment, a plan was implemented to create a bicameral conference committee to approve a final version of the bill stripping the added language, but this plan was abandoned after a large contingent of House members staged a walk-out in the final hours of the legislative session in protest of election-related legislation under consideration, stopping all House action in its tracks and leaving dozens of bills to die due to the end of the legislative session.

With retiree benefits and billions in taxpayer money at risk, the State Senate quickly reversed its objection to the House amendment in an effort to save Senate Bill 321 from death by inaction before the legislative calendar ran out of time, in essence passing the House-approved version of SB 321, including the retire-in-place amendment.

It is our hope and understanding that key legislative leaders intend to resolve this outstanding issue with SB 321 in the special legislative sessions expected to be called this year. It is important to convey that this imprudent amendment does not weaken the overall importance and effectiveness of the reforms in Senate Bill 321. The bill, as passed in both chambers of the state legislature, still represents a major piece of comprehensive and lasting reform on one of Texas’ major pension plans.

6. Conclusions and Next Steps

Looking forward, stakeholders should continue to seek ways to reduce long-term costs. While SB 321 already commits the state to higher annual contributions, even more savings could come from additional supplemental payments to the significant debt of the legacy plan.

Texas policymakers should be on the lookout for opportunities to direct extra funds to accelerate the payment of the state’s pension debts. They should also consider adopting shorter amortization schedules, which would save the state even more in long-term costs. There is also still work that can be done to reduce the risk and volatility by adopting assumptions that are more certain to be achieved by ERS. This will involve lowering the plan’s unrealistic assumed rate of return.

Stakeholders should also apply their experiences with this reform to the state’s other major pension plan, the Teacher Retirement System of Texas (TRS), which faces many challenges and would benefit from a similar collaborative reform process.

Minor last-second challenges aside, Senate Bill 321 is an outstanding reform of the Employees Retirement System that effectively addresses the challenges facing Texas and the public pension plan. State policymakers and other parties involved in the process should be commended for fostering a collaborative process based on actuarial forecasting and for providing an outstanding pension reform model that many other states can follow.