As the cost of living continues to soar, homeownership is increasingly out of reach for many young Americans. The Consumer Price Index, a widely used measure of inflation, rose to 9.1% in June to reach the fastest year-over-year increase since November 1981. Rapid inflation, combined with interest rate hikes intended to slow its growth, has pushed the cost of homeownership to record highs. But these recent trends are just exacerbating longer-term causes of home price increases: inadequate supply and excessive regulatory costs, particularly in high-demand coastal metros where young people prefer to live. Housing policy reforms are urgently needed to increase the supply of housing, reduce the burden on American households, and place homeownership back within the reach of younger adults.

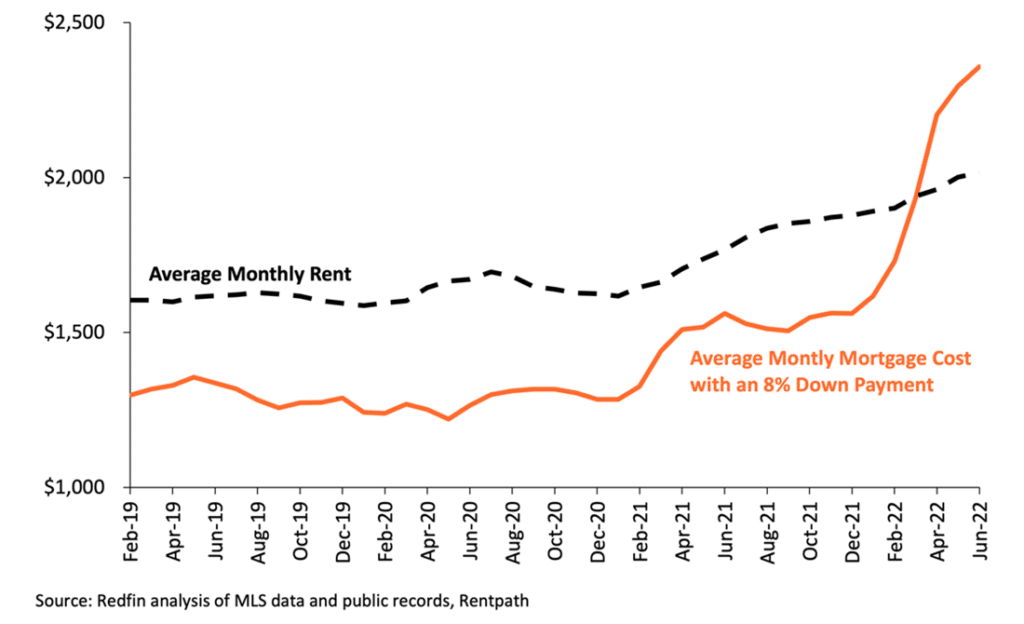

A confluence of supply chain disruptions, rising interest rates, and a persistently inadequate supply of housing units has thrown the housing market out of balance. While monthly mortgage costs have traditionally been lower than monthly rents, that calculus has started to change. This is especially true for young, first-time homebuyers who typically make smaller down payments, which result in higher monthly mortgage costs. According to data from the National Association of Realtors, the median down payment of buyers between the ages of 23 and 31 is 8% of the purchase price. The median among all home buyers is 13%, but older homebuyers can often afford much more.

Data provided by Redfin, a national real estate brokerage, suggests that average monthly rents rose by 14 percent in June compared to the same month last year. Over that same period, the average monthly mortgage payment for new homebuyers jumped by 51%, primarily driven by rising interest rates and sustained home price growth. With monthly mortgage costs outpacing rent, it may now make more sense––at least in terms of monthly expenses––for many Americans to rent than to own. For homebuyers with an 8% down payment (the average among the millennial cohort), the average monthly mortgage cost was $2,358, compared to the average monthly rent of $2,016. In June of last year, average monthly mortgage costs with an 8% down payment would have been $206 less than the average rent.

Figure 1. Average Monthly Rent vs Mortgage Costs

Of course, national averages only tell part of the story. Rents, home prices, and composition of the housing stock vary considerably across metropolitan areas. For example, the monthly cost difference between renting and owning in Los Angeles, California, is approximately $1,640 assuming an 8% down payment. In Dallas, Texas, the difference is only $234 per month. Meanwhile, monthly mortgage costs are actually $278 cheaper than the average rent in Cincinnati, Ohio, according to the Redfin data.

Rising costs could exacerbate generational disparities in homeownership as millennials enter the prime homebuying age. Millennials have generally trailed behind previous generations when it comes to homeownership. A recent Apartment List report found that:

Among the oldest batch of millennials who reached age 40 in 2021, the homeownership rate is 60 percent. In comparison, 64 percent of Gen Xers, 68 percent of Baby Boomers, and 73 percent of Silents owned homes when they were the same age.

This observation is often attributed to millennials having different housing preferences than previous generations. While there may be some merit to this idea, the vast majority of millennials state a preference for owning over renting. According to the Apartment List report, only about a quarter of millennials plan to “always rent” instead of buying a home. Among those who expect to be lifetime renters, 77% cited their inability to afford a home as a reason.

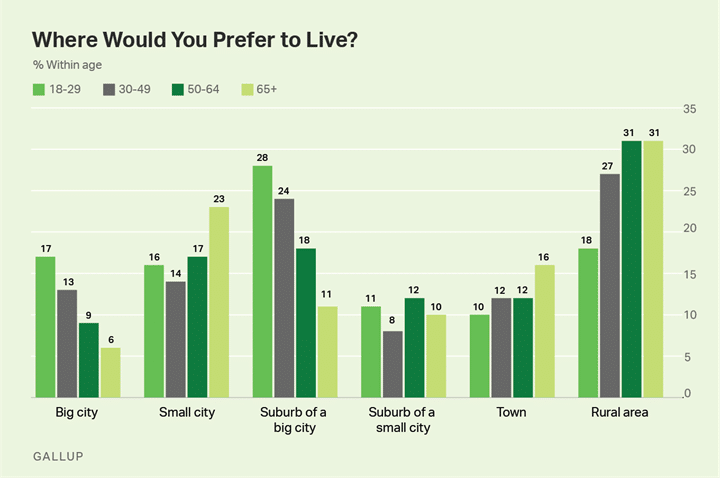

However, location preferences are one generational difference that could explain some of the disparities in homeownership. Polling from Gallup suggests that younger Americans would prefer to live in the suburbs of large cities while older Americans would prefer to live in rural areas. This finding is consistent with the notion that millennials would prefer homeownership, but are unable to afford homes in the expensive metro areas where they want to live.

Figure 2. Location Preferences by Age Group

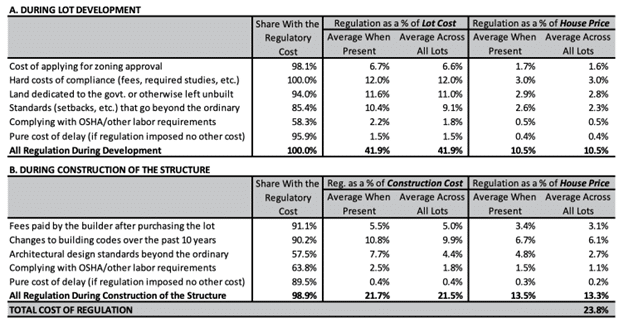

Since the 1980s, home prices have generally risen faster than construction costs (such as building materials and labor). Researchers have generally attributed this divergence to an increasing regulatory burden. Regulatory requirements add to the cost of housing by restricting supply, imposing fees, and creating delays in the construction process. A 2021 report by economist Paul Emrath found that regulatory costs add an estimated 23.8% to the final sale price of a home. In the first quarter of 2022, the median sale price of a single-family home was $428,700. According to Emrath’s estimates, regulatory costs accounted for approximately $102,030 of that price.

Figure 3. Average Regulatory Costs (Percentage)

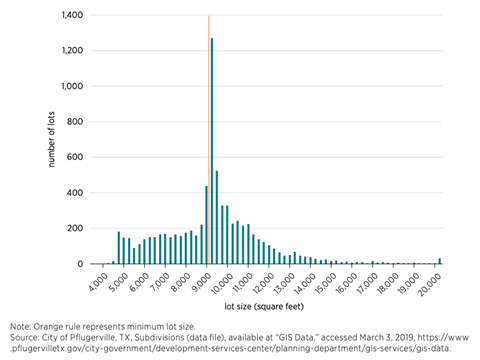

Among the many housing policies that impose regulatory costs and constrain the supply of housing, lot-size minimums are among the most common and pernicious. In nearly every municipality in America, minimum lot-size regulations specify the smallest allowable size for a parcel of land. These requirements effectively limit the number of housing units that can be built in a given area and force homebuyers to purchase more land than they otherwise might, increasing the cost of housing.

A recent study by economist Salim Furth and urban planner Nolan Gray examined the impact of lot-size minimums in four Texas cities. The authors found that developers tend to build homes on lots that are very close to the minimum lot size. For example, in the Texas town of Pflugerville, homes in most areas have a minimum lot size of 9,000 square feet (slightly over 0.2 acres). About 32% of all lots in Pflugerville are between 9,000 and 10,000 square feet and only 19% of lots are over 10,750 square feet. This finding suggests that builders and consumers would likely opt for smaller-sized lots if they were permitted.

Figure 4. Pflugerville, Texas, Lot-Size Distribution and Minimum Lot Size

According to American Enterprise Institute estimates, land values––on average––account for nearly 55% of the price of a home in the United States. In high-demand metro areas where land values make up a significant portion of home prices, minimum lot sizes can have a substantial impact on the cost of homeownership. For example, in New York City, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Miami, land values can account for as much as 70% of home prices. To the extent that lot-size minimums in these areas force homebuyers to purchase more land than they otherwise would, municipal governments are directly pricing young Americans out of homeownership.

Excessive land-use regulations, including lot-size minimums, are part of why land values are so high in these cities. According to an index developed by researchers at the Wharton Business School:

Nine of the top 10 markets in terms of measured regulatory strictness are situated along either the Northeast Coast (from Boston down through Washington, D.C.) or the West Coast of the country (Seattle, Portland (OR), San Francisco, and Los Angeles).

These regulations have significant consequences for would-be homebuyers. Excessive regulations not only make it less affordable for young people to purchase homes in the metro areas where they prefer to live, they may also hamper economic mobility and contribute to rising regional inequality in the United States.

In the short term, high-interest rates and supply chain disruptions are expected to persist. Regardless of whether these factors subside in the longer-term, regulatory costs and a shortage of housing will continue to squeeze prospective homebuyers. Policymakers should pursue regulatory reforms such as reducing lot-size minimums, lowering fees, and adopting more flexible zoning to ensure that the American Dream remains within reach for generations to come.