There’s been a lot of recent concern in New Jersey and elsewhere about the way public sector pensions are investing their assets, largely focused on the fees associated with investing in hedge funds and other “alternatives.” Assembly Bill 4704, which unanimously passed the New Jersey Assembly and now sits in the Senate’s Budget and Appropriations Committee, would require state-run systems to conduct stress tests on their investment portfolios and disclosure of investment policies, including fees paid to managers.

In principle this seems prudent. Pension funds should have a better idea of how much they’re paying their asset managers, and pensioners and taxpayers have a right to know how their money is being invested. Even though there’s very little to object to on face, it’s important that these policies supplement, not substitute, more robust reform efforts.

Public employees and their representatives are right to be concerned about fees associated with alternative investments, especially when they’re not publicly disclosed. Many state and local pension systems have improved their handling of their alternative investments, sometimes by divesting from them altogether. For example, the Kentucky Retirement System announced plans to fully remove hedge funds from its portfolio last November.

This is good, but the champions of these proposals rarely ask, “why do we need to be invested in these risky alternatives in the first place?” One need not be a cynic to recognize that some of the rhetoric surrounding management fees and investment in alternatives more broadly is as much about bashing Wall Street (or Greenwich in the case of hedge funds) as it about the health of public workers’ retirement security.

Opposition to current pension investments with hedge funds isn’t all bark. Some states like California and New Jersey are looking to drop their investments in hedge funds to try and get a better price. As Tom Byrne, chairman of the New Jersey State Investment Council put it last July, “[y]ou’re losing clients because your prices are too high? Lower your price. That’s capitalism.”

But negotiating better deals with hedge funds isn’t easy, even for multi-billion dollar pension funds. First, if a particular pension system is able to extract concessions like more favorable fee schedules from hedge funds, on the margin they’ll be attracting worse hedge funds. “Fund that are doing well, that are attracting or are closed to new capital just aren’t going to change. They don’t have to accept fee demands from investors” CEO of alternative investment consultancy Cliffwater LLC Stephen Nesbitt told Pensions & Investments.

Second, even if a plan is able to retain higher-quality hedge funds, these funds may only have a good track record in the near-term, instead of actually being quality investment vehicles for the long-run. As I’ve discussed in a previous post, a 2009 study found that 90% of hedge fund managers failed to outperform the market — which fits basic economic and finance theories that you can’t beat the market in the long run. Ironically, the purpose of hedge funds is to defy this efficient market hypothesis, to achieve higher returns than simple investment in stocks and bonds could yield. It just doesn’t always work out that way.

In short, betting on hedge funds or other alternative investments is betting that your investor is smarter than the market.

This generally isn’t a smart bet. 2016 in general was a mediocre year for hedge fund investments, even including improvements after the 2016 election. A number of funds believe that the Trump could ignite “animal spirits” and make alternatives a more profitable investment, but given the political volatility we’ve seen of late, caution is the best route.

It should go without saying that government-run pension systems should be risk-averse when investing money that isn’t theirs (i.e., the taxpayers’ and pensioners’), but investing in alternatives isn’t automatic financial suicide. A Cliffwater LLC report found that between 2006 and 2015about two-thirds of plans studied were able to outperform a simple 65/35 mix of stocks and bonds by investing in alternatives.

How were these plans able to outperform their peers? The report found that some funds were just better at managing their investments than others, but, as stated above, since there’s so much luck associated with hedge fund investments, perhaps these plans themselves were just lucky.

All of this is to say that investing in alternatives isn’t necessarily bad. It’s often a good idea to invest a small share (5-10%) of a portfolio in riskier assets to reap some windfall gains while shielding yourself from large downside risk. This is the basic idea behind the “barbell theory” developed by Geman, Geman, and Taleb (paper here). Essentially, for most of your portfolio you want to cap downside risk by investing in near-zero risk assets (such as Treasuries), but leave some assets available to capitalize on high-return events (good “black swans,” as Taleb would call them).

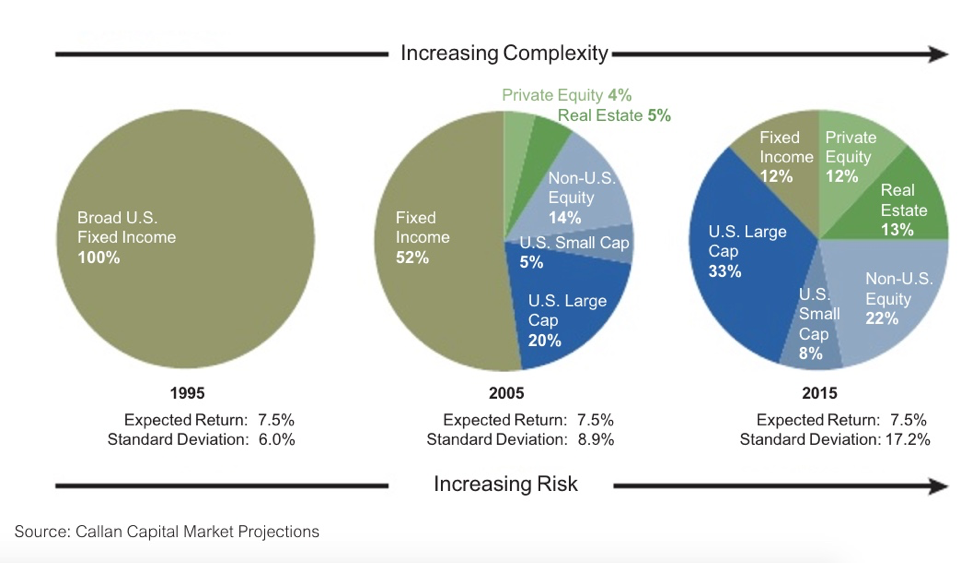

Many pension funds, however, are going well beyond what the barbell theory suggests is the optimal asset allocation. In 2000, the average pension fund invested only 3.6% of assets in alternatives, compared to 16.4% today. And the rest of these assets aren’t invested in low-risk assets like treasuries. Below is figure showing the different asset allocations required to achieve a 7.5% rate of return (about the average for plans across the US).

To achieve a 7.5% expected return, pension systems must invest in more volatile assets—ranging from equities (risker than bonds, but still relatively safe) to hedge funds and other alternatives—today than they did 20 years ago. So while investing in hedge funds isn’t a guaranteed loss and a small portfolio of alternative assets can be beneficial, high variance (shown above by increasing investment return standard deviation) means counting on these investments to save a foundering pension fund is a risky strategy at best.

The failure of hedge fund investments to bring about pre-Financial Crisis investment returns isn’t a question of transparency or fee negotiation. The global economy has entered a “new normal” of low investment returns due to structural problems such as slowed population growth, China’s matured relationship with respect to international trade, and a general decline in dynamism in the global economy. All of this means that low investment returns are going to be with us for the short- and medium-term.

Hedge funds and other alternative investments are risky, sure, and there are many pension funds that have done a poor job of managing these investments. But in the Garden State’s case, the State Investment Council already stress tests their investments and discloses fees.

Codifying these policies in statute certainly makes sense, but policymakers should also realize that the new normal of low investment returns, the high volatility (and luck) associated with high hedge fund returns, and the need for plans to take on greater risk to meet their current return targets means that additional pension reforms designed to tackle the structural problems associated with current pension systems are necessary to address New Jersey’s current crisis.

Even the labor associations realize that. In a statement announcing support for the bill, the New Jersey Education Association (NJEA) said, “the crux of New Jersey’s pension struggle will not be resolved by investment strategy…but [NJEA] maintains that additional pension funding would do far more to improve the health of our pension funds.”

The proposed policy would be an improvement, but it would be unfortunate indeed if it reduced policymakers’ demand for substantive reform by creating the illusion that the problem has been fixed. It’s also praiseworthy for groups like the NJEA to give full-throated support for better funding policy, but as long as these funding policies are predicated on faulty assumptions designed to fund unsustainable retirement benefits, measures like AB 4704 will amount to little more than a drop in the bucket.