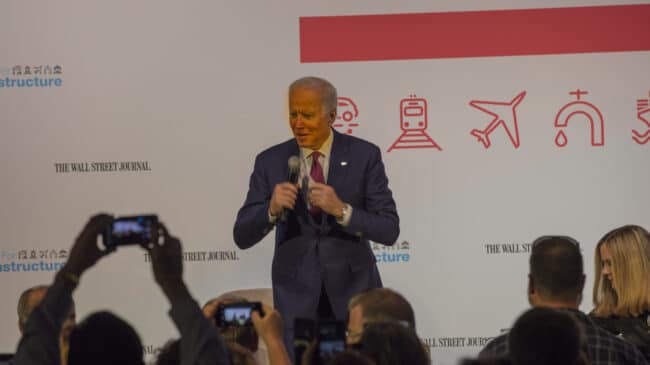

Private infrastructure financing and long-term public-private partnerships have once again become a subject of debate as President Joe Biden pushes for a bipartisan infrastructure bill and various congressional proposals contend for support. The White House has reached an agreement with a bipartisan group of senators on a $579 billion infrastructure proposal that includes “public-private partnerships” as about $100 billion of the plan’s proposed pay-fors.

Without any details on how it would work, this element has come under serious attack. To be sure, a public-private partnership is a procurement method, not a funding source.

When it comes to highways, the likely funding source for a design-build-finance-operate-maintain (DBFOM) public-private partnership would be tolls on the highways, which are pure user fees. And if tolls are properly understood as user fees, they should not violate President Biden’s insistence that no new taxes on middle-class Americans be used to pay for this or other bills.

Likewise, a new per-mile charge (not a per-mile tax) would be a viable source of revenue for public-private partnerships (P3s) to be used to rebuild and replace aging Interstate highways and bridges, or to add more express toll lanes to congested urban freeways.

Attacks on the P3 component of the bipartisan Senate proposal have been hot and heavy. Politico wrote that this would not be “new federal funding”:

“The latest proposal envisions spending $579 billion in new money. But virtually all of the proposed pay-fors aren’t realistic. Three of the pay-fors — an infrastructure financing authority, public-private partnerships and municipal bonds — involve incentivizing private investment, which is not new federal funding. And five of them have been essentially rejected by the White House — a fee on electric vehicles, indexing the gas tax to inflation and three separate bullet points that all involve repurposing Covid relief funds.“

I thought the idea was that America is trying to address a several-trillion-dollar backlog of infrastructure needs, not maximize the amount of federal spending.

Some progressive attacks on the bipartisan infrastructure proposal have been silly and ill-informed. Economist Paul Krugman referred to an alleged Trump administration plan for tax credits for private investors in infrastructure, which was an idea floated by transition team member Wilbur Ross prior to the 2016 election—a ridiculous idea that never went anywhere. Krugman wrote:

“When Trump’s advisers unveiled his infrastructure ‘plan,’ I realized that he was carefully avoiding hinting that we could build infrastructure like Eisenhower did. On the contrary, it proposed a complex and surely unfeasible system of tax deductions for private investors who would build, it was hoped, the infrastructure we needed. If Trump’s folks had ever set out to create an infrastructure plan, it probably would have resembled the only investment program the government has put in place, creating “zones of opportunity” that were supposed to help Americans living in zones. low income. What that program ended up doing was bringing wealth to wealthy investors, who took advantage of tax breaks to build, for example, luxury homes.”

While infrastructure week became an ongoing joke during the Trump administration, the actual Trump administration proposal was drafted by a serious transportation expert, D. J. Gribbin, and laid out an agenda that would have expanded the scope for tax-exempt private activity bonds (PABs) and encouraged states to seek long-term public-private partnership leases to rebuild aging infrastructure.

The same foolish equation of the Ross tax-credit concept and framing the current proposal as a “stalking horse for privatization” was used by The American Prospect’s David Dayen piece. And on June 23, a Harvard Ph.D. student, Brian Highsmith, went further in a New York Times op-ed, attacking “user fees like road tolls and a new fee on vehicle miles traveled” as some sort of evil imposition on hapless motorists (as if we did not have 100 years of highway user fees called fuel taxes and thousands of miles of toll roads).

Fortunately, many mainstream organizations are speaking out in favor of tapping private capital via long-term public-private partnerships as part of the solution to America’s infrastructure needs. The Business Roundtable and the Bipartisan Policy Center have argued for a bipartisan infrastructure plan that would “unlock private capital and encourage public-private partnerships,” suggesting a $1 trillion total investment in actual physical infrastructure. Their plan also calls for Congress to require that projects seeking federal funding “conduct public-private partnership screens, using value-for-money analyses to select the most efficient and cost-effective project delivery method.”

In the House, the bipartisan 58-member Problem Solvers Caucus has offered its own $959 billion plan for traditional infrastructure, including expansion of PABs and the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA), as well as incentives for states to embrace long-term public-private partnerships and to create P3 units.

These are promising signs, but they are hardly a guarantee that such proposals will make it into actual legislation. It is time for the transportation and P3 community to speak out, showing legislators and opinion leaders the important role that private capital (from public pension funds, insurance companies, and infrastructure investment funds) can play in financing infrastructure—and are already playing in other parts of the world.

These U.S. audiences need to understand that private infrastructure investors do not seek or need tax credits. What they do need is ample amounts of tax-exempt private activity bonds and access to flexible TIFIA loans. But they also need more states to enact workable long-term public-private partnership enabling legislation and create specialized P3 units. That is how the United States will generate many more projects suitable for private investment.

Two other federal policy changes would also open up large P3 opportunities. One is to clarify PABs legislation to make it clear that this kind of revenue-based financing can be used not just for new (greenfield) projects but also to rebuild/replace/modernize aging infrastructure, such as obsolete Interstate bridges and entire long-distance Interstate highway corridors. The other is to liberalize federal tolling restrictions.

The Transportation Research Board’s massive 2018 study on the future of the Interstates estimated the cost of rebuilding and modernizing this critically important asset as about $1 trillion over the next several decades. Yet there is no mention of this huge need in any of the current infrastructure proposals.

Congress could at least open the door by allowing willing states to use toll financing and public-private partnerships to begin rebuilding Interstates, which are this country’s most valuable transportation asset. That could be enabled simply by expanding the current Interstate System Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Pilot Program (ISRRPP) to all 50 states and all their Interstate corridors. Unfortunately, the House surface transportation reauthorization bill would actually abolish ISRRPP rather than expanding it.

What we don’t need right now are public officials singling out some of the best megaprojects and candidates to be public-private partnerships to get ‘free’ federal taxpayer money instead of using P3s. Alas, that is what President Biden did in May, stressing the federal government’s role in infrastructure on the site of Louisiana’s planned toll-financed P3 to replace the obsolete I-10 bridge in Lake Charles.

The business community—groups like the Business Roundtable, national Chamber of Commerce, National Association of Manufacturers, etc—should be speaking out strongly in favor of private capital investment in needed megaprojects, where the potential for cost overruns and other risks can be shifted to the shoulders of investors, rather than hapless taxpayers.

Public pension funds, too, which want to invest in P3 infrastructure (and are doing so mostly overseas due to too few U.S. projects) should also be speaking out. Ensuring the retirement security of public employees would be yet another bipartisan argument in favor of a larger role for P3s in America’s infrastructure.

A version of this column first appeared in Public Works Financing.