Drug laws were relaxed in several states through voter initiatives in the 2020 election, but the most drastic change took place in Oregon, where voters approved a statewide ballot measure to decriminalize drugs. In projecting what lies ahead in Oregon, it is worth looking at Portugal’s overwhelmingly positive experience with decriminalization.

Ballot measure 110, supported by 58.5 percent of Oregon voters, decriminalized the possession of small amounts of all drugs, including heroin and cocaine. The voter initiative reclassified possession of these substances from a misdemeanor to a simple violation. Instead of a jail sentence, individuals found with so-called hard drugs will face a completed health assessment or a $100 fine. The reclassification only applies to possession of amounts reflecting individual use, and criminal penalties remain for anyone found distributing or manufacturing illegal drugs.

Oregon has some of the highest rates of substance abuse in the country and a report from the Oregon Substance Use Disorder Research Committee found that one in 10 Oregonians struggle with a substance use disorder (including both drugs and alcohol). The challenges posed by substance abuse disorders are worsened by Oregon’s particularly poor levels of accessibility to treatment services. Incarceration of those with substance use disorders has proven to be ineffective. It is not a deterrent to drug use, it does not make drug users any safer and it doesn’t reduce risks of overdose.

Beyond the relaxation in law enforcement efforts related to drug use, Measure 110 also places a greater focus on wellbeing and care for individuals with substance abuse issues in Oregon.

The measure, financed by a diversion of existing marijuana tax revenues, includes the creation of an oversight and accountability committee to distribute grants related to recovery and addiction treatment services. Committee members will include state residents who have struggled with substance abuse disorders, formerly incarcerated individuals, and experts within the drug treatment community. New 24/7 addiction recovery centers will be established to conduct health assessments and facilitate a path to sobriety for those who wish to avoid the $100 fines that may be assessed. Access to the treatment centers is available for everyone in the state—not just those who come into contact with the police.

All in all, Oregon’s new drug policy seeks to reduce high rates of substance abuse by removing the punitive aspect of drug policy and instead of treating individuals’ underlying mental health and addiction problems. Fundamentally, this approach recognizes that addiction is a mental health condition that often requires treatment to overcome.

Understandably, some Oregonians are concerned that decriminalization will lead to a surge in drug use. However, the data suggests otherwise. Several countries, including Switzerland and the Netherlands, have decriminalized the personal possession of drugs. The first country to do so was Portugal in 2001. Portugal’s decriminalization policy aimed to improve the worsening health of the country’s drug-using population, particularly those who injected drugs.

Like Oregon, one of the central aspects of Portugal’s policy was the establishment of free treatment facilities along with information campaigns about the harms of drug use and needle exchanges. Individuals found with drugs on their person were charged with an administrative offense that required them to be seen before a committee where they were either offered treatment or a small fine.

Interpretations of the drug use data in Portugal vary widely depending on the metrics used, however, a collation of figures from the Transformation Drug Policy Foundation found that decriminalization, on the whole, was not associated with a rise in drug usage. Drug use rates in Portugal are now below the European average for cocaine, methylenedioxymethamphetamine, and amphetamines.

With nearly 20 years of data and documentation to assess the success of the policy, it is unsurprising that Oregon’s Measure 110 was largely inspired by Portugal. A wide body of research has shown a lack of relationship between the severity of drug laws and rates of drug usage. The studies focusing on drug use amongst adolescents are particularly reassuring.

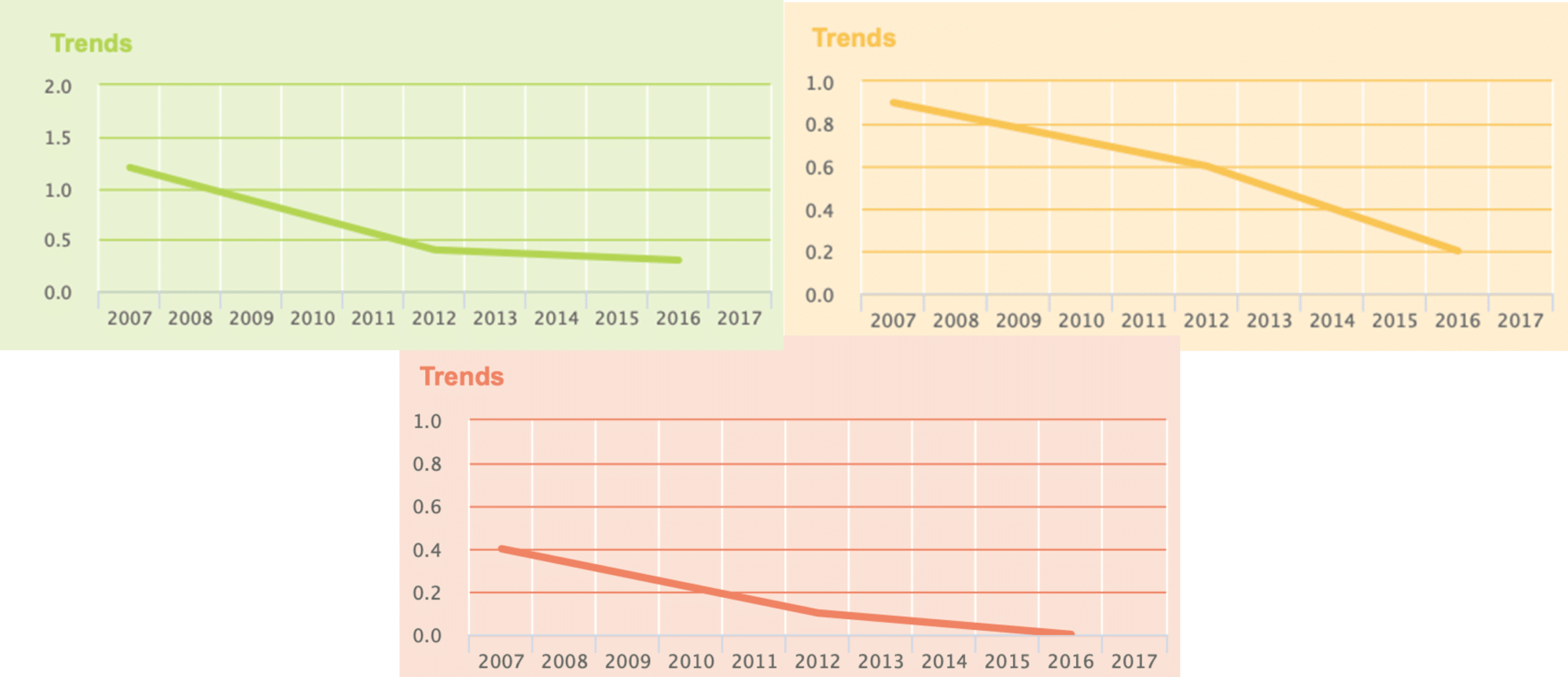

Tracking the drug use of adolescents (aged 15-to-34) over time in Portugal has shown a steady decline in the use of cocaine, amphetamines, and MDMA between 2007 and 2012. Figure 1 below shows that since 2012, there has been an even greater decline in cocaine use. More generally, continuous drug usage (relating to individuals who use drugs regularly) has decreased since decriminalization. These results certainly do not constitute a surge in drug use.

Figure 1: Young Adults In Portugal Reporting Use of Drugs

(left to right: cocaine, methamphetamines, and amphetamines)

Source: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Addiction.

Data from Portugal suggests that many benefits arise from treating drug use with health services instead of criminalization including a reduced burden on the criminal justice system, a reduction in deaths caused by overdose or drug-related illnesses, and a reduction in addiction rates.

Although some still fear Oregon’s new policies may increase drug use, but history in Portugal and elsewhere shows these results are unlikely to materialize in the state. And should Oregon’s policy succeed in reducing the negative effects of substance abuse problems, other states should soon consider implementing similar policies.