New York City Mayor Bill De Blasio announced in September that he would be seeking private firms to fill the staffing shortages at the city’s Rikers Island Correctional Facility. Far from a supporter of private prison companies, De Blasio recognizes that the poor conditions at the jail have accelerated as the staff has failed to show up for work in record numbers—even compared to 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit the city harder than anywhere in the country. Unfortunately for the overcrowded and understaffed jail, a 2002 law written and promoted by the New York Correction Officers’ Benevolent Association (COBA) bans the mayor from hiring outside help from the private sector.

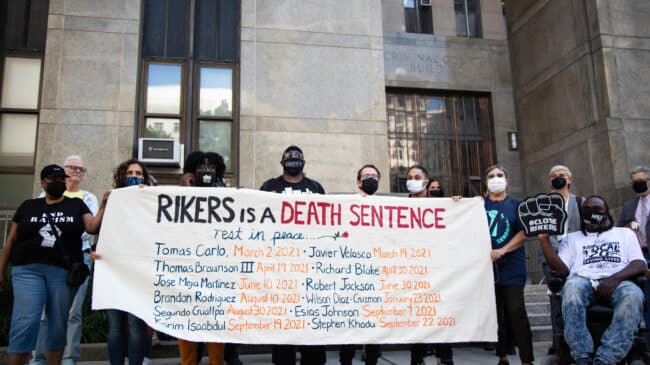

The already bad conditions at Rikers have become worse. Officers walking out and calling in sick to avoid work has gotten so bad that the city is threatening to suspend officers without pay for going AWOL. In August, the New York City Department of Correction noted over 2,700 AWOL incidents, and an average of 1,500 officers calling in sick every day (up from 689 in the same month last year).

The lack of available officers has left the remaining staff to work harder and more frequently, with staff often taking double or triple (24 hours straight) shifts. Inmates are often left unattended, as getting time out of their cells, receiving food, medicine, meeting with counsel and other services often depend on sufficient staff being present to securely handle such functions.

When staff exists en masse, both inmates and remaining staff suffer.

Instead of welcoming the relief sought by De Blasio, the Correction Officers’ Benevolent Association would rather play politics by defending the 2002 law, insisting their staff attendance will only get better if more are hired into COBA’s ranks. The law is there “to protect inmates from the barbaric hands of privately run prisons,” COBA’s president insists.

The 2002 law would allow for police to help out in the city’s corrections ranks. But the New York City Police Department says it has enough of its own work to deal with, lamenting 100 officers being forced to help out at the jail. That leaves bringing in private security firms or hiring more COBA staff (who would operate under the same collective bargaining agreement that currently makes it possible for so many COBA staff to avoid working) as the only options to increase staffing levels.

Unsurprisingly, COBA, the nation’s largest municipal corrections union, has long opposed any participation from the private sector in New York City corrections. The union’s staff run Rikers and the state’s prisons. Private prison staff isn’t allowed inside of them. Private prisons have played no role in Rikers’ sorry state.

De Blasio, recognizing an already-terrible situation is getting even worse, is looking to the private sector for help, for the benefit of inmates and staff who interact with inmates. This includes guards, for certain, but also doctors and nurses, therapists, legal counsel, and other non-COBA members. If COBA could handle this problem themselves, they would have by now.

Absent competition, the incentives aren’t there for COBA’s workers, who have made it a habit of not showing up for work to show up for work more often. The city and state are still taking steps that could help staffing issues. The city is considering options to force many officers to come back to work through the threat of suspension. And ‘Less Is More’ legislation signed by Gov. Kathy Hochul in September will release many Rikers inmates over technical parole violations and other nonviolent infractions. But both positive steps won’t begin to bear any fruit until at least next year.

COBA’s wish to keep its members insulated from any competition while allowing conditions at Rikers to continue to deteriorate and their own ranks to increasingly walk away from the job or stay at home as much as possible makes it clear that the status quo is not working.

Rikers is certainly not alone in severe overcrowding and understaffing problems. Alabama and California both have faced federal sanctions in their state prison systems recently for the same reasons, but they have made efforts to address those problems. In New York, Rikers’ problems have remained unaddressed for years and are clearly getting worse. Letting the private sector use existing resources to help provide some relief to Rikers is a no-brainer, but COBA would rather play politics and act like they aren’t part of the jail’s problems.