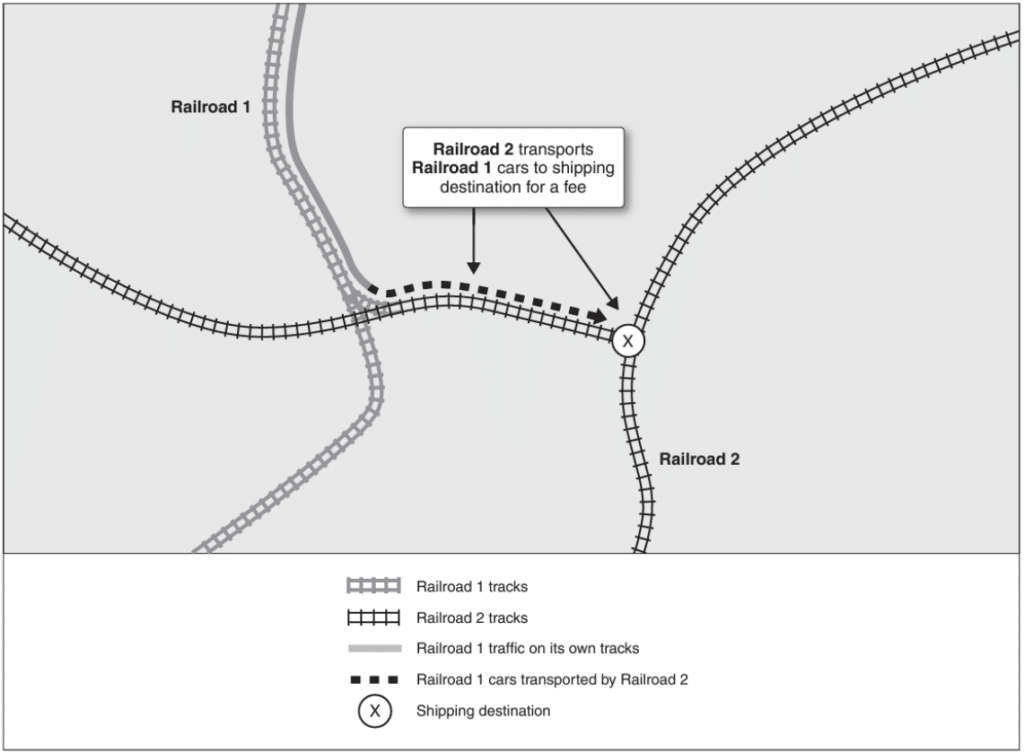

Energy policy analyst Philip Rossetti of the R Street Institute recently called for increasing regulation on freight railroads to promote transportation competition. Specifically, Rossetti argues for weakening the evidentiary requirements that must be met prior to mandating “reciprocal switching,” a practice in which one carrier exchanges traffic of another to allow customers access to a facility served by only one carrier and providing the customer a single-line rate from the rail carrier that does not physically serve the facility. Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of the practice.

Figure 1: Reciprocal Switching

Source: Government Accountability Office (2007)

The political clash over mandatory reciprocal switching dates back decades. In the 1980s, the now-defunct Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) established evidentiary requirements before the agency could impose reciprocal switching agreements on carriers, most significantly a demonstration of anticompetitive conduct of a rail carrier. These ICC decisions were affirmed by federal courts, most notably in Midtec Paper Corp. v. United States in 1988. In the years that followed, shippers were unable to prove the existence of any anticompetitive conduct in the rail industry.

While some would celebrate the apparent good conduct of the railroads, this failed to satisfy some shippers seeking mandatory reciprocal switching. After more than a decade of consideration of a shipper lobby petition, the Surface Transportation Board (STB), the ICC’s successor agency, published revised regulations on reciprocal switching in April 2024. These new regulations take effect this September. The final rule discards the anticompetitive conduct requirement and allows shippers to seek mandatory reciprocal switching if a rail carrier fails to meet the STB’s performance standards related to service reliability and consistency.

Watering down the standards of evidence makes it easier for shippers to force railroads to interchange each other’s traffic, but some believe the STB didn’t go far enough. Rossetti is one of them and takes the rather extreme position where mandatory reciprocal switching should be the default, rather than an avenue of relief when operational metrics can justify it.

Rossetti’s position in favor of mandatory reciprocal switching rests on two main arguments: Railroads are natural monopolies akin to traditional electric utilities, and Canada’s experience has proven that such a regulatory scheme would work well in the United States. Both claims miss the mark.

Freight railroads are not public utilities

First, freight railroads in the United States are not natural monopolies comparable to electric utilities. Most rail customers are served by multiple transportation options, either multiple railroads or other modes of transportation, such as barges and trucks. The concern is primarily about a minority of “captive shippers,” those customers who cannot economically choose another transportation option other than the incumbent railroad.

While there is no definitive list or even definition of what constitutes a captive shipper, what might be termed “more captive” shippers exhibit two common characteristics: They produce or use low-value bulk commodities such as chemicals, coal, and grain that cannot be economically transported by trucks; and they operate in remote or low-density areas that lack navigable waterways suitable for barge transportation.

These more-captive shippers have been the principal focus of railroad economic policy since partial deregulation under the Staggers Rail Act of 1980. The Staggers Act’s most important provision was the legalization of contract rates, which allow rail carriers and their customers to negotiate customizable service contracts to best suit their needs, rather than rely on common carrier tariff rates that impose one-size-fits-all pricing and service. As I discussed at length in a 2022 Reason Foundation report, greater pricing freedom enabled by the Staggers Act saved freight railroads from extinction (or nationalization), improved service for shippers, and led to substantial declines in average rates.

Due to their operating characteristics, more-captive shippers should be charged higher prices that reflect their heightened risk to the railroads. The rail lines serving these shippers tend to have few other customers. If a more-captive shipper served by a low-density rail line goes out of business or chooses to move facilities, the railroad’s fixed private right-of-way and track infrastructure investments remain. A significant amount of the scholarly debate on post-Staggers railroad pricing has focused on the appropriate markup that should be charged to more-captive shippers to account for their heightened sunk-investment risk to railroads. Recognizing this, the goal of differential freight rail pricing is to ensure more-captive shippers are not harming the majority of non-captive rail customers while still providing railroads an incentive to serve more-captive shippers in the first place.

Furthermore, the comparison of railroads to electric utilities is fundamentally flawed because rail traffic does not at all resemble electrons moving through wires. Electric utilities, often operating under monopoly franchises while using public rights-of-way, produce and distribute uniform units of electricity. In contrast, rail traffic is highly diverse and moved by specialized railcars and equipment for each commodity type.

Rail customers seeking to move imported school supplies in a shipping container to a retail distribution center have very different expectations than customers seeking to move a chlorine tank car from a chemical plant to a water treatment facility. That freight railroads do not move identical, interchangeable units of cargo is a central fact that underpins railroad economics and serves as the basis for modern rail policy.

In recent years, the U.S. railroad industry has moved to implement efficiency-enhancing practices commonly referred to as precision scheduled railroading (PSR), a term coined three decades ago by the late railroad executive Hunter Harrison. These practices generally involve running longer trains with shorter transit times on fixed schedules, emphasizing general-purpose manifest trains (trains that carry cars with different types of freight) over unit trains carrying single commodities, and pre-classifying as many railcars as possible to minimize time- and labor-intensive car switching between trains in rail yards.

While the goal is to reduce operating expenses and offer more reliable service, the impacts have been controversial. More-captive shippers have been among the loudest critics of PSR. This is likely because most of them produce or use low-value bulk commodities that were previously moved by unit trains that were held for long periods as customers gradually added railcars to trains. With railroads implementing consistent service schedules and moving away from unit trains, those shippers have likely faced challenges in adopting their own operations to better fit PSR practices.

With respect to mandatory reciprocal switching, increasing the number of railcars switched violates key PSR principles and would undermine the whole enterprise. In this sense, calls for mandatory reciprocal switching can be viewed as an attack on PSR and a backdoor method of enforcing the previous status quo that happened to benefit certain shippers. Mandating lower-productivity railroading may satisfy some shippers who are unwilling to modernize their own operations, but should not be considered a legitimate goal of rail policy.

Appeals to Canadian interswitching are inapt

Since the early 20th century, the Canadian government has imposed mandatory reciprocal switching, which it calls “interswitching.” Interswitching in Canada is granted whenever a shipper requests it, and a switching point between two competing railroads is within a 30-kilometer (18-mile) radius of the shipper (or 160 kilometers in western Canada), after which rates based on the number of railcars and shipment distance are applied.

American supporters of mandatory reciprocal switching, like Rossetti, frequently cite the Canadian experience with interswitching as a guide to likely outcomes of mandatory reciprocal switching in the United States. However, this is not a like-for-like comparison and provides little insight into what we might expect from the imposition of Canadian-style interswitching on the United States rail market. For instance:

- The Canadian rail market has two dominant Class I carriers centered in the eastern (Canadian National) and western (Canadian Pacific Kansas City) areas of the country. In contrast, the United States has four dominant Class I carriers that serve the eastern-to-central (CSX, Norfolk Southern) and western-to-central (BNSF, Union Pacific) regions, with the two Canadian Class I carriers providing substantial service in the central United States.

- Canada has approximately 40 short-line railroads that feed into its two Class I carriers. The United States has more than 600 short-line railroads that feed into its six Class I railroads, more than 15 times the number of short-lines as Canada.

- Canada has a rail network composed of approximately 28,000 route-miles. The United States has a 140,000-mile rail network. Network density measured by route-miles of track per square mile is five times greater in the United States.

These vastly different rail network characteristics aren’t the only reasons why comparisons between Canada and the United States are inapt. Perhaps most importantly, Canadian interswitching was mandated more than a century ago and the Canadian rail network was developed around this policy. It would be unwise to expect that the imposition of Canadian-style interswitching on the mature U.S. rail network would lead to similar outcomes.

Further, in comments to the STB, Canadian Pacific noted several other important facts about Canada’s experience with interswitching, including:

- The vast majority of interswitched traffic occurs voluntarily and does not involve regulators.

- Canadian National and Canadian Pacific have little visibility into each other’s interswitched traffic, so Canadian Pacific cannot plan for cars originated by Canadian National that then arrive at an interchange point a day later. This “traffic-flow blindness” makes it much more challenging to address unexpected congestion when it occurs since the railroads have no control over a large share of traffic that is handled by interchanges.

- Interswitching by definition increases operational complexity, which in turn increases asset and crew demands as well as dwell times. Canada’s rules provide some flexibility to manage these inefficiencies, but interswitching still imposes sizeable costs on carriers and shippers in the form of higher operating expenses and traffic delays.

In the United States, passenger railroads led by the Commuter Rail Coalition have strongly opposed mandatory reciprocal switching due to anticipated delays arising from increased operational complexity and have called on the STB to reconsider its recent final rule. In an earlier reciprocal switching proceeding at the STB, parcel carrier UPS told regulators that it had concluded that mandatory reciprocal switching “will lead to decreased network velocity, diminished capital investments into the freight rail network, and deteriorating rail intermodal service levels” and force the company “to move these containers and trailers back onto the highway.”

While shifting intermodal rail traffic back onto the highway might benefit trucking companies, it would deprive railroads of their most lucrative revenue source, limit freight transportation competition, and reduce rail network investment to the detriment of all shippers. In addition to these private costs, a shift of traffic from rail to truck would also produce large social costs.

According to a Government Accountability Office analysis, truck accident fatality rates are six times greater than rail’s, and injury rates are 17 times higher. According to Environmental Protection Agency data, when compared to freight rail, trucks produce approximately 10 times as much carbon dioxide, more than three times as much fine particulate matter, and two-and-a-half times as much nitrogen oxides per ton-mile.

Conclusion

Rossetti’s desire for greater freight transportation competition is laudable, but mandatory reciprocal switching is not the way to pursue that goal. One interesting feature of mandatory reciprocal switching is that neither rail carrier consents to the agreement. The “competition” is imposed on two rail carriers under duress, requiring them to give their competitors access to their private property. This makes for an odd form of “competition.”

As I’ve noted for years, the real danger of mandatory reciprocal switching is freight rail stagnation. In testimony to the U.S. House Railroads Subcommittee last year, I made the case that partial economic deregulation of freight rail has greatly benefited carriers, customers, and consumers. Imposing new operational mandates for the perceived benefit of a select class of shippers would reverse those gains.

The main challenge facing freight rail going forward lies in its ability to compete with increasingly automated trucks, which are expected to be introduced into commercial service in the United States later this year. Freight rail, too, must automate and reduce operating costs to remain competitive, including for traffic commodity groups where rail has traditionally faced little to no truck competition. Unfortunately, various re-regulatory proposals threaten the industry’s ability to do so, a subject I expanded on in a presentation at a recent conference held by the Transportation Research Board of the National Academies.

I am hardly alone in warning of the dangers of mandatory reciprocal switching. In addition to Reason Foundation, analysts with the American Enterprise Institute, Cato Institute, Competitive Enterprise Institute, Hoover Institution, International Center for Law and Economics, Mercatus Center, and numerous other free-market think tanks have come out against it. This list includes the R Street Institute, which in the past called mandatory reciprocal switching “a solution in search of a problem” and wrote that arguments in its favor are “based on a pair of faulty assumptions.” While different analysts can hold different views within the same organization, I humbly suggest that the R Street Institute had it right the first time.