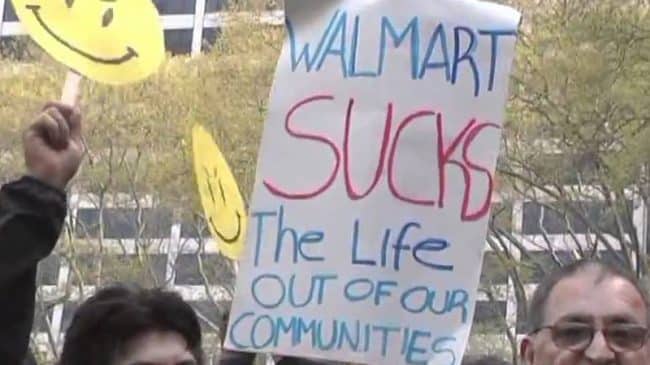

Well, they won. Earlier this month, Wal-Mart® was officially defeated in Inglewood, with more than 60% of voters coming down against a measure that would have permitted the building of a Wal-Mart super-center. Among those most opposed was political strategist Mike Shimpock, whom the Los Angeles Times quoted as declaring that the victory sent a clear signal of how “Wal-Mart can’t dupe people in this city to sign away their rights.”

It seems somewhat odd, however, that anybody would claim that the city’s rights were at stake. What liberties are involved when a city prevents a business from moving in? Does Inglewood exist in some parallel universe where cities are entitled to “freedom from Wal-Mart?”

Surely that can’t be the case, so Shimpock and his fellow activists must have something else in mind. Alas, the most probable explanation is no more amenable to reason. What Shimpock was most likely hinting at is the idea that every community has the right to establish whatever standards it wishes for land usage, standards which inevitably become exceedingly complex and difficult to comply with.

This is certainly the case in Inglewood. Though relatively small, Inglewood has 29 articles in its zoning code, controlling everything from condominiums to parking areas. The code regulates attributes such as building height, yard dimensions, and land usage. It also includes no fewer than 12 separate taxes.

In attempting to bypass certain troublesome elements in the zoning code, Wal-Mart was accused of scheming to violate peoples’ rights. The conglomerate had the sheer audacity to attempt to exempt itself from this tangled maze of regulation by putting the issue before the people of Inglewood in a referendum.

Yes, it’s an extreme solution to a difficult problem, but tyrannical? Hardly.

Yet to the various bureaucrats and self-appointed community activists, Wal-Mart has still committed a grave sin: It tried to bypass them and their much vaunted authority and instead go directly to the people. Wal-Mart may have failed, but it still tried. The precedent alone frightens entrenched powers.

Accordingly, this entire ordeal – the ads, the posturing, and the referendum itself – was not so much about the rights of the community as it was about control. What voters regrettably failed to appreciate, however, is that this control is far from positive. By applying zoning restrictions that prevent “big box” stores such as Wal-Mart from being built, Inglewood is missing out on an ideal source of new jobs and inexpensive goods.

Contrary to what those celebrating with the outcome of this plebiscite may believe, disliking Wal-Mart as a company is not an adequate reason to oppose their expansion. It is often said that in the free market, individuals vote with their dollars. Accordingly, if Wal-Mart was truly despised by the citizens of Inglewood , the super-center would have failed.

However, it is zoning that makes this a political issue rather than a matter of free market competition. Zoning is used as a legal bludgeon to keep out supposedly “unwanted” businesses.

This isn’t limited to Wal-Mart, either. In Oakland , McDonald’s has recently been denied permits that would allow them to build a restaurant in the Grand-Lakeshore shopping district. One local activist, Jim Ratcliff, was quoted in the San Francisco Chronicle as referring to the McDonald’s project as a “threat” that “has energized our neighborhood with a sense of crisis.”

Owen Courrèges is a research fellow in urban and land use policy at the Reason Foundation