In July 2025, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to “End Crime and Disorder on America’s Streets,” which called for stronger law enforcement involvement in addressing visible homelessness and addiction. While the order frames these challenges as stemming from criminal disorder, the data tell a different story.

With the U.S. homeless population reaching a record 771,480 people in Jan. 2024, an 18% increase from the previous year, it’s clear that enforcement alone cannot solve a problem of this scale, prompting questions about how the executive order will be implemented and whether it will be at all effective.

Policies that emphasize consistent housing access, coordinated public health services, and law enforcement practices designed to de-escalate crises and connect people to support offer a more durable path forward. Instead of focusing on punitive enforcement, lawmakers should take a harm reduction approach to homelessness and public safety.

Harm reduction is a practical public policy approach focused on reducing preventable harm and improving stability. An interdisciplinary harm reduction framework uses harm reduction as a guiding mindset for policymaking across housing, public safety, and health. This approach shifts the focus from punishment to engagement and from short-term control to long-term stability by aligning incentives across policy areas to address the underlying drivers of harm, rather than their symptoms. In applying this framework to the problem, two priorities emerge.

First, housing reform, particularly zoning reform, can reduce barriers that keep people unhoused and expand access to stable, affordable options that support recovery and safety. Second, if law enforcement continues to play a role, officers must be adequately trained to respond to behavioral health and substance use conditions common in those who are unhoused. This includes trauma-informed care, de-escalation techniques, and clear referral pathways to treatment and housing services. Then, when these aspects of housing, health, and public safety are connected through a harm reduction lens, policy can move beyond crisis management toward coordinated, cost-saving, compassionate solutions that reduce harm and promote lasting stability.

Treating homelessness as a public health problem

The Council of State Governments (CSG) recently released a brief to guide planning, implementing, and assessing law enforcement responses to homelessness through an interdisciplinary, harm-reductive framework, focusing on what is often the first level of contact and intervention. Police are often the first, and sometimes the only point of contact for the unhoused, yet police have historically had few tools or partnerships to respond effectively. Understanding what those encounters look like starts with the data.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, approximately 26% of adults who are unhoused have a serious mental illness, and another 26% have a chronic substance use disorder, compared with 5-6% and 3% of adults in the broader population, respectively. Research shows that many individuals experience co-occurring conditions, and substance use is often intertwined with untreated or undertreated mental illness. As a result, when law enforcement officers respond to visible homelessness, they are frequently engaging with people managing complex, overlapping behavioral health conditions in addition to housing instability. One study finds that those who are unhoused have up to 47% higher odds of serious mental illness when compared to those who were stably housed.

Encounters between police and unhoused people with mental illness or substance use disorders often unfold under tense, high-risk conditions. Among people experiencing both homelessness and mental illness, 62% reported at least one police interaction over four years, most often as suspects, and those with substance use disorders faced the most frequent encounters. People with mental illness are also more than 11 times more likely to experience police use of force than those without such conditions, and nearly one in four police shootings involves someone with a mental health condition. On the other side of things, the way policing currently operates often makes these encounters even more volatile.

These data do not suggest that police should be responsible for resolving homelessness, mental illness, or substance use, nor do they imply that law enforcement is equipped to address these challenges beyond immediate crisis response. The core function of policing remains the rapid stabilization of dangerous situations and the removal of immediate threats to public safety.

However, Trump’s executive order creates a new operational reality in which law enforcement is being asked to play a more central role in managing visible homelessness and associated disorder. A global review of 92 studies found that repeated or adversarial police contact not only fails to resolve underlying problems but can worsen them—intensifying stress, anxiety, and even suicidal thoughts, especially among people already living with trauma or instability. These encounters, as they currently exist, are dangerous—for the person being handled and for the officer responding.

This is where a harm reduction approach becomes essential. Responding to homelessness, mental illness, and addiction through enforcement rather than engagement perpetuates crisis and risk on both sides, when there are other ways to go about it. The CSG brief emphasizes that progress starts with aligning shared goals across law enforcement, behavioral health, and housing to ultimately reduce the revolving door between homelessness, jails, and emergency care.

California has shown early promise with collaborative approaches that pair law enforcement diversion with housing and behavioral health partnerships, and the state is increasingly leaning into these models as alternatives to enforcement-led responses. These alternatives include co-responder and outreach teams that pair law enforcement with mental health or social service professionals to de-escalate crises, homeless outreach models that emphasize sustained engagement and service navigation rather than repeated enforcement, navigation centers that centralize housing placement, case management, and behavioral health services, and specialized law enforcement units trained in trauma-informed and behavioral health–informed response to support stabilization and referral. No single executive order or institution can solve this problem on its own. Real progress depends on coordinated systems that enable both responders and the people they encounter to find stability and safety.

Why trauma-informed law enforcement training matters

Trauma is a central factor shaping interactions between the unhoused and law enforcement, with direct implications for public safety outcomes and the effectiveness of enforcement-based responses. Research from the National Health Care for Homeless Council on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), which are potentially traumatic events that occur before the age of 18, shows that while roughly 12% of the general population reports four or more ACEs, that figure rises to 53% among the unhoused. ACEs are measured using a cumulative scoring system in which experiences such as physical and sexual abuse, neglect, household dysfunction, and exposure to violence are considered. Higher ACE scores are associated with lasting changes in how the brain processes threat, stress, and safety.

In policing contexts, trauma can shape how individuals neurologically perceive and respond to threat, producing involuntary physiological and behavioral reactions that may be misinterpreted during law enforcement encounters. Brain research shows that trauma can alter how the brain detects danger and regulates stress. Studies have found that people with long-term trauma exposure can experience reductions of 8% to 26% in brain regions associated with memory and decision making. These neurological changes help explain why hypervigilance may appear as constant threat scanning, dissociation may present as disengagement or silence, and freeze responses may be mistaken for intentional noncompliance during police encounters.

These dynamics are especially relevant in interactions with unhoused individuals, who experience disproportionately high rates of trauma. Data from the National Health Care for the Homeless Council show that homeless people report childhood physical abuse at roughly three times the rate of the general population, sexual abuse at four times the rate, and emotional abuse at seven times the rate. When trauma-shaped survival responses are misread as defiance or suspicion, routine encounters can escalate unnecessarily.

At the same time, trauma exposure is not limited to civilians. Research examining police interactions with vulnerable populations also highlights how repeated exposure to violence, crisis, and human suffering shapes officer behavior. A law review analysis by the University of Arkansas found that officers experience an average of three traumatic events every six months on duty, a level of exposure that can heighten threat perception if left unmanaged. Qualitative interviews with 48 U.S. police officers found that trauma was widely perceived as an inevitable part of the job and was associated with heightened threat perception, defensive cognition, and altered engagement strategies. Officers described becoming more guarded, enforcement-oriented, or avoidant in routine encounters, with trauma exposure influencing how they assessed risk, interpreted intent, and exercised discretion. These shifts affected not only use-of-force decisions but also everyday interactions, including communication style, willingness to engage, and responsiveness to community members. Trauma-informed policing is designed to address this dynamic directly. Defined in the literature as a system-wide approach, it requires law enforcement agencies to recognize the impacts of trauma, understand how adversity shapes behavior, and respond through policies and practices that promote safety, trust, and de-escalation while actively avoiding re-traumatization. Evaluations by the Center for Naval Analyses and the International Association of Chiefs of Police show that trauma-informed and victim-centered practices improve cooperation during investigations, reduce re-traumatization, and strengthen long-term trust between communities and law enforcement. Together, this evidence suggests that policing strategies grounded in an understanding of trauma and human behavior can reduce unnecessary escalation and improve outcomes during public encounters.

What trauma-informed policing looks like in practice

In practice, trauma-informed policing is not a single program or training requirement. It is a coordinated, inter-agency approach that requires alignment across law enforcement, behavioral health, housing, and court systems. This framework recognizes that people experiencing mental illness, substance use disorders, and housing instability move through multiple public systems over time and seeks to reduce unnecessary justice system involvement at every stage by ensuring these agencies share information, protocols, and goals.

Police-led diversion is a key component of this approach and is distinct from traditional prosecutor-led or court-led alternatives to incarceration. Research by the Center for Court Innovation found that 21% of law enforcement agencies operate formal diversion programs in which the decision to route an individual away from the traditional justice process is made at the discretion of officers or the agency itself. These pre-booking interventions keep individuals out of the court system entirely, reducing both system costs and the collateral consequences of arrest for people in crisis.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, police-led diversion programs have expanded significantly since 2016, with the majority led by law enforcement agencies and more than half involving direct connections to treatment. These programs take several forms: self-referral programs where individuals voluntarily seek assistance from law enforcement; active outreach by officers or co-responders to identify people who need services; post-overdose follow-up connecting individuals to care within 72 hours; and field interventions where officers connect people to services rather than initiating charges.

Programs such as Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD), which originated in King County, Washington, in 2011, demonstrate this approach. LEAD diverts individuals engaged in law-level drug offenses, prostitution, and crimes of poverty away from the criminal legal system, bypassing prosecution and jail time, instead connecting them with intensive case managers who provide crisis response, psychological assessment, and long-term wrap-around services, including substance use disorder treatment and housing.

Evaluation research found LEAD participants were twice as likely to obtain shelter and 89% more likely to secure permanent housing compared to traditional processing. In Colorado, LEAD pilot programs showed a 50% reduction in re-arrest among participants. The Houston Police Department’s Mental Health Division pairs officers with licensed clinicians in co-responder units, and between 2010 and 2014 diverted over 9,500 individuals, with 90% of encounters involving an arrestable offense resolved through diversion rather than formal charges. The Vera Institute of Justice identifies pre-arrest diversion as particularly effective for people who need access to substance use or mental health treatment, connecting them with support that addresses underlying needs rather than issuing punishments.

The most effective frameworks prioritize resolving crises outside the criminal justice system whenever possible. Many behavioral health emergencies do not require a law enforcement response at all. Communities that invest in mobile crisis teams, crisis call centers, warmlines, and peer support services create alternatives that allow people in distress to access care without being arrested or charged. When these services are available around the clock and well coordinated, situations that would otherwise result in police contact can be addressed through health and social service responses.

To be clear, none of this applies when someone poses an immediate threat to public safety. Officers responding to a person with a weapon must prioritize public safety, effective disarmament, and humane resolution–in that order–regardless of whether the individual is experiencing a mental health crisis, intoxicated, or traumatized. But encounters with most unhoused individuals may not involve weapons or violence. They involve someone in crisis on the sidewalk, complaints about encampment, or behavior that is disruptive but not dangerous. In these situations, officers have discretion, and diversion programs give them an alternative to arrest.

Police are responsible for addressing immediate safety concerns, but they are not expected to serve as long-term treatment providers or housing coordinators. Trauma-informed policing is most effective when it focuses on what officers can realistically do: stabilize a crisis and connect the person to the appropriate system. The savings, both human and fiscal, come from ensuring that housing, health, and community systems are equipped to take over once the officer leaves.

The default responder dilemma

Police are often the default first responders when the public encounters visible homelessness. Call data from San Francisco alone shows that police were dispatched to over 98,000 homelessness-related incidents in 2017. Officers are routinely called to assist when a person is in crisis on a sidewalk, when encampments draw complaints from residents, or when behavior becomes unsafe for the individual or others nearby. This reliance on officers places them in roles they are not equipped to fulfill—serving as de facto social workers, mental health counselors, and housing navigators without the training, resources, or statutory authority these roles require. Across the country, outreach-oriented responses in which officers attempt to connect individuals with social services or support represent the most common discretionary police response to homelessness identified across U.S. jurisdictions.

Most calls involving homeless people are legitimate requests for police assistance: someone behaving erratically or combatively due to mental illness or drug use, someone on private property whose presence is driving away customers, or someone whose behavior poses a risk to themselves or others. These are valid reasons to call the police, and law enforcement officers are the only ones with authority to physically remove someone from a location or intervene when safety is at risk. The question is not whether police should respond to these calls, but whether every call requires a sworn officer as the sole responder. In some jurisdictions, 311 systems and dispatch protocols have been updated to identify calls that can be handled by civilian crisis teams without law enforcement, freeing officers to focus on situations that actually require their authority and training. This is not about dispatching a crisis team to every police contact–it is about improving triage so that officers are not repeatedly sent to calls that do not require enforcement while ensuring they remain available for calls that do.

Research from the R Street Institute emphasizes that trauma-informed criminal justice is most successful when embedded in a broader, coordinated system of care. This continuum includes accessible community mental health services around the clock, housing-first programs that do not require sobriety or treatment compliance, peer support specialists integrated into crisis response teams, and follow-up services that address the root causes of instability rather than merely managing immediate crises. Each of these services improves outcomes in its silo, but offering them during an important touchpoint, like when being approached by police, offers a toolkit to address even the most complex of problems.

Housing as the anchor: Aligning land use with harm reduction

Housing stability is one of the most important determinants of long-term health, education, and overall well-being. Repeated displacement, overcrowding, and ongoing threats of eviction create stress that harms both physical and mental health. These conditions also disrupt access to health care, interfere with learning, and make it difficult for individuals to maintain steady employment. For those who experience instability over long periods, the effects are cumulative, shaping outcomes across generations. A stable home provides the foundation for consistent health care, education, and employment, and it remains one of the most effective forms of prevention and recovery for individuals and families alike.

Yet for many low-income renters, even financial assistance fails to guarantee stability. The Florida Policy Project’s Elevating Housing Vouchers Report highlights that long wait times, landlord discrimination, and a chronic shortage of available units prevent housing voucher programs from fulfilling their intended purpose. Recipients often spend years on waiting lists only to find that, once approved, there are few landlords or units available to accept vouchers. The report concludes that without a sufficient supply of affordable housing, vouchers cannot function as an effective market solution. This finding shows that housing assistance programs, while critical, depend on the availability of housing stock. Expanding supply is therefore not an ancillary policy goal, but the essential precondition for making existing housing programs work.

An essential layer of this continuum involves housing and land use policy. A growing body of research highlights that zoning regulations and restrictive land use policies often determine where housing, treatment, and harm reduction facilities can be located. These restrictions frequently delay or prevent the creation of supportive housing or service sites that could stabilize individuals at risk of homelessness or substance use crises.

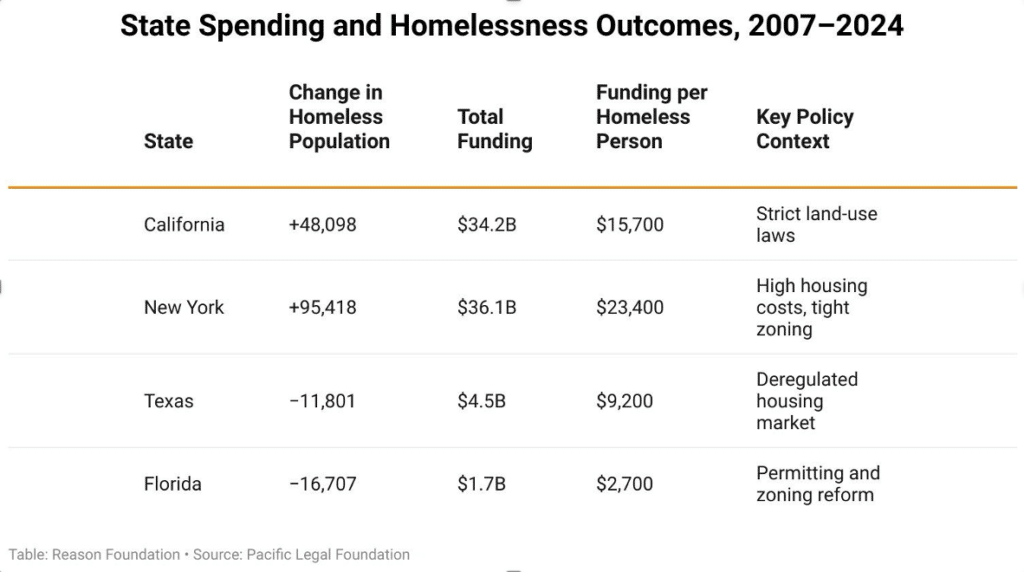

States that have implemented regulatory reforms to increase housing construction have shown significant progress in reducing homelessness, often with limited public expenditure. For instance, between 2007 and 2024, Florida’s homeless population decreased by over 16,700 people, and Texas saw a reduction of nearly 11,800. In contrast, states with more stringent land use regulations, such as California and New York, experienced substantial increases in homelessness despite much higher spending. California, for example, spent approximately $34 billion on homelessness programs during this period, while Florida spent less than $2 billion, yet Florida achieved a more significant reduction in its homeless population.

In this context, “homelessness programs” refers to spending on shelters, transitional housing, outreach, case management, and related services. These programs are designed to respond to homelessness after it occurs. They do not address the underlying shortage of housing (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Spending and homelessness outcomes in select states

Recent research published in the Urban Affairs Review found that only about 30% of major cities explicitly link their homelessness strategies to zoning or land-use reform, despite clear evidence that local planning decisions directly shape housing supply and affordability. The authors also note that many cities lack integrated frameworks that link housing policy, public health, and homelessness response, leaving agencies to operate independently rather than in coordination.

Local governments play a crucial role through their planning and permitting decisions, yet many communities fail to coordinate their homelessness and housing strategies. Cities with higher rates of unsheltered homelessness are often the least likely to mention land use in their homelessness plans, revealing a disconnect between public safety responses and long-term housing solutions. Integrating harm reduction principles into zoning and planning practices, such as allowing the adaptive reuse of vacant buildings for treatment or transitional housing and removing unnecessary barriers to supportive and recovery housing, can help create more stable environments where public health and housing strategies reinforce one another.

These barriers are not abstract. Across the country, zoning rules have repeatedly blocked efforts to provide housing and services for those who are unhoused. In Florida, Talbot House Ministries faced resistance when it sought to expand its shelter in Lakeland because its property was zoned nonresidential. In Montana, the Flathead Warming Center had its permit revoked after neighborhood opposition, leaving people without shelter during the winter. In North Carolina, the Catherine H. Barber Memorial Shelter was denied a permit despite meeting all zoning requirements, and in Minnesota, officials rejected a permit for an accessory dwelling unit intended to house a family in need.

Each of these cases demonstrates how zoning codes, often influenced by community opposition or outdated classifications, can prevent local governments and private actors from addressing homelessness. Reforming local zoning to allow shelters, supportive housing, and small residential units in more neighborhoods would remove a major barrier to stability and bring land-use policy closer into alignment with harm-reduction goals.

Policy recommendations

A harm reduction framework is effective because it links three interdependent agencies: health, public safety, and housing. Each component strengthens the others. Harm reduction reduces immediate risks and builds trust. Trauma-informed policing promotes safety and de-escalation. Expanded housing supply provides the stability necessary for long-term recovery. When these elements work together, they address both the immediate and structural causes of homelessness and addiction, replacing fragmented crisis responses with sustained pathways to stability.

The following recommendations outline how this integrated framework can be applied in practice:

- Bring in peer recovery coaches and civilian crisis teams: To strengthen the approach, agencies should expand their partnerships to include peer recovery coaches and civilian crisis response teams. Both are critical in turning moments of crisis into opportunities for engagement. Evidence shows that peer recovery services can significantly improve recovery-related outcomes. A systematic review by the Recovery Research Institute found that across 24 studies (N = 6,544), individuals receiving peer-based support demonstrated reduced substance use and relapse rates, higher treatment retention, better relationships with providers, and greater satisfaction with care. Civilian crisis response teams build on the same principle of human-centered intervention. In Denver, the Support Team Assisted Response (STAR) program handled 748 calls in its first six months—none requiring police backup—and reduced low-level crime reports in pilot areas by 34%. Together, these approaches offer an efficient model worth leaning on, especially in communities where resources are limited and every response matters.

- Redefine success through broader outcome measures: A trauma-informed framework redefines what success looks like by shifting the focus from control to healing. Traditional measures such as arrests, citations, or crisis response volumes fail to capture the long-term impact of policy and practice on people’s lives. Instead, trauma-informed systems evaluate progress through indicators of recovery, safety, and stability–such as sustained housing, engagement in voluntary treatment, reduced re-traumatization during service interactions, and improved perceptions of trust and fairness among residents. These data points, when reviewed together, offer a fuller picture of community well-being and institutional effectiveness. They also help agencies identify patterns of harm and refine their strategies to promote healing rather than perpetuate crises. This approach works because it promotes alignment across agencies and reduces duplication of services by ensuring a true continuum of care. When data from housing, health, and public safety systems are integrated, communities can identify service gaps, coordinate responses, and invest resources where they have the greatest impact. By treating feedback and lived experience as central to continuous improvement, trauma-informed systems evolve to support dignity, empowerment, and long-term recovery rather than fragmented or repetitive interventions.

- Align housing and land use policy with harm reduction principles: The final piece of the puzzle involves housing and land use. Zoning laws and permitting decisions often determine whether a city can build the spaces people need to recover. States that have streamlined housing construction by reducing zoning barriers, like Florida and Texas, have seen notable declines in homelessness even with comparatively lower public spending. In contrast, states with more restrictive land use policies, such as California and New York, continue to face rising homelessness despite far greater investments. These outcomes show that expanding housing supply through permitting reform, smaller lot sizes, and flexible zoning is essential to long-term stability. Local governments hold tremendous power through their planning departments, yet many still operate in silos. By integrating harm reduction principles into zoning and planning practices, such as converting vacant buildings for transitional housing or easing restrictions on supportive housing, cities can create environments where public health and housing strategies reinforce one another.

Together, these roles create a clearer division of responsibility, where police stabilize immediate crises, outreach professionals manage ongoing care, and housing and behavioral health systems provide long-term solutions that reduce the need for police intervention over time.

Turning harm reduction frameworks into foundations

The Council of State Governments framework offers a strong foundation, and an integrative harm reduction approach would strengthen it. Its focus on shared goals, measurable outcomes, and cross-sector coordination lays the groundwork for lasting change. Still, housing, public health, and police response reform remain the missing pillars in many state strategies, even though long-term recovery depends on stable homes, access to care, and compassionate crisis response. Integrating housing, public health, and police reform into harm reduction efforts ensures that safety initiatives are matched with pathways to treatment, stability, and well-being.

Used as a foundation rather than a finish line, the CSG framework can guide policymakers toward a future where public safety and public health work together—and where progress is measured not by enforcement avoided but by lives stabilized.

To achieve this, states must move beyond pilot programs and temporary funding cycles toward sustained, outcome-driven investments that prioritize coordination over control. Policymakers have the tools to build systems that treat homelessness and addiction not as crises to contain, but as challenges to solve through evidence, empathy, and accountability. Public safety reform should not be defined by how many arrests are made, but by how many people are safely housed, connected to care, and able to rebuild their lives.