Beginning roughly 30 years ago, cities across the U.S. subsidized a wave of new professional sports stadiums based on promises of major economic impact from the new facilities. But those stadium projects failed to live up to their original promises. Today, despite a much better understanding of just why stadiums are not economically justifiable public investments, a similar wave of stadium subsidies is surging across the country. In city after city, state and local elected officials are incurring hundreds of millions—if not billions—of dollars in debt and future obligations to replace or update what team owners are characterizing as “outdated” 30-year-old stadiums.

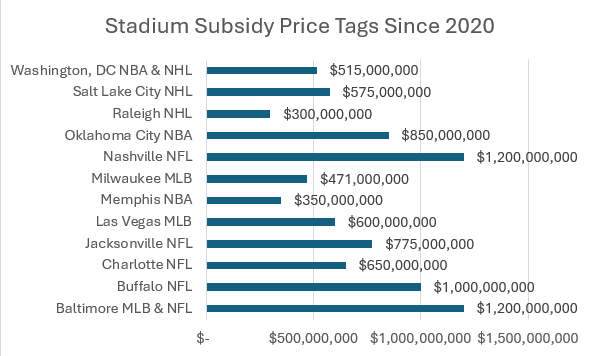

Stadium subsidy announcements have burgeoned over the past few years. Since the end of the COVID-era restrictions on spectators attending professional sports events, top-tier professional sports teams in Baltimore, Buffalo, Charlotte, Jacksonville, Milwaukee, Nashville, Oklahoma City, Raleigh, and Washington, D.C. have all secured government subsidies to build or significantly update their stadiums.

Meanwhile, faced with municipalities that wouldn’t give in to their demands, the Arizona Coyotes of the NHL announced a move to Salt Lake City, and the Oakland A’s announced a move to Las Vegas, with a layover in Sacramento’s minor-league stadium while their new location works out the financial and legal details. Likewise, teams in Anaheim, Chicago, Indianapolis, Kansas City, Memphis, New York City, Philadelphia, San Antonio, St. Paul, St. Petersburg, and Washington, D.C. are actively shopping or negotiating new or renovated stadiums—and other teams elsewhere in the country are floating trial balloons, arguing that their stadium needs to keep pace with the competition.

The “retro classic” midlife crisis

One major reason for the 30-year clock ticking on these stadiums is that many cities and states are finally paying off the 30-year bond debts incurred to build them in the first place. Team owners see an opportunity to tap back into that well of money, and local officials prefer to renew “temporary” surcharges, ticket taxes, or other mechanisms rather than allow them to expire and lose the associated tax revenues. One common argument is that these taxes “have to be used for stadiums,” but elected officials should be seriously considering the concept of eliminating the tax once the stadium is paid off. Moreover, the current stadium renovation deals often carry much bigger price tags than the original cost to taxpayers to build the stadium in the first place, even when adjusting for inflation. Baltimore’s Camden Yards, for instance, cost $110 million to build in 1992, the equivalent of $246 million in 2024 dollars. Earlier this year, the Maryland state legislature passed a law granting the Orioles the equivalent of a $600 million line of credit to use to update the stadium, along with another $600 million for their next-door neighbor Baltimore Ravens to use to update their football stadium.

That means that renovations to the existing baseball stadium, which is still younger than the oldest two players on the Orioles’ roster, could potentially cost more than twice as much in inflation-adjusted dollars as the stadium cost to build in the first place.

Similarly, in Jacksonville, the local government approved $775 million in subsidies simply to renovate and update the Jaguars’ EverBank Stadium, which was built in 1995 at a cost of $134 million—roughly $275 million in today’s dollars.

While these deals are indefensible in their own way, the true danger from a public policy perspective is that they could well be the first few stones of an avalanche of such deals across the country. It would fit the pattern established by these and other stadiums that were built or remodeled in the early 1990s when Camden Yards triggered a “retro classic” stadium trend. Teams designed stadiums that intentionally hearkened back to historic “jewel box” ballparks such as Fenway Park or Wrigley Field with intentionally quirky design features. Then teams in other sports followed suit with their own new, purpose-built stadiums.

Before that point, the prevailing stadium model had been a 1960s or 70s-era concrete bowl “municipal stadium” first popularized by Robert F. Kennedy Stadium in Washington, D.C. Owned by local government, these stadiums hosted multiple sports teams as rent-paying tenants, with football and baseball teams often sharing the venues such as Oakland Coliseum, Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh, Shea Stadium in New York City, Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia, Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati and Busch Stadium in St. Louis. In some places, the bowls got a domed roof, with the Houston Astrodome leading the way for stadiums such as Minneapolis’ Metrodome, the Pontiac Silverdome in the suburbs of Detroit, Atlanta’s Georgia Dome, the Superdome in New Orleans, Seattle’s Kingdome, the Hoosier Dome in Indianapolis and the RCA Dome in St. Louis.

The college counterfactual

While pro sports teams claim they need shiny new stadiums and arenas to attract fans to games, the steadfast popularity of college sports calls that argument into question.

The oldest major conference stadium, Georgia Tech’s Bobby Dodd Stadium, was built in 1913. However, that age doesn’t appear to discourage either fans or sponsors. An average of 34,600 fans have attended Tech home games the past five years, while in 2023 the university signed a $55 million, 20-year naming rights deal to call it “Bobby Dodd Stadium at Hyundai Field.”

While Tech may be perennial underdogs in football with only five winning seasons in the past decade, reigning national champions Michigan still sell out 107,901-seat Michigan Stadium for every home game despite the “Big House” being 97 years old.

All told, 22 of the 70 teams in the top “Power Five” college football conferences play in stadiums that are a century or more old. In fact, more major college football teams play in stadiums first built before the invention of broadcast television than in ones that were built this century.

Meanwhile, roughly a third of NFL stadiums aren’t yet old enough to legally order a beer.

Stadium economics: fair or foul?

Most of these stadiums became economic albatrosses for their communities and they’re almost entirely gone now, cleared away by the tide of new stadiums that justified their price tags with promises of economic growth and renewal. But while all but a few cranky economists—and Reason writers—could be forgiven for yielding to those promises three decades ago, there’s no excuse now. Essentially all the 1990s-era stadiums failed to deliver promised economic growth and prosperity surpassing their joyless predecessors, producing real-world results that rarely even came close to promises and predictions.

The three-decade-old stadiums undergoing replacement or renovation at great taxpayer expense failed so catastrophically at economic development that they have united economists in rare, nearly unanimous condemnation. One prominent sports economist, Kennesaw State University Professor J.C. Bradbury, sums up that consensus bluntly: “When you ask economists if we should fund sports stadiums, they can’t say ‘no’ fast enough.”

In 2017, the University of Chicago’s Booth School polled its “U.S. Economic Experts Panel” of high-profile economists on whether subsidizing sports stadiums was likely to generate a positive return for the government. A confidence-weighted 83 percent of the panel that included seven Nobel Prize winners in economics agreed that stadium subsidies aren’t worth the cost, 11 percent weren’t sure and just 4 percent—one single economist—were in favor.

The self-funded counterfactual

Despite what team owners say, some professional sports teams do pay for their stadiums and arenas—and it doesn’t keep them from competing for championships.

Perhaps the best-known example of this is in Los Angeles, where Los Angeles Rams owner Stan Kroenke has reportedly spent roughly $5 billion of private funding to build SoFi Stadium in Inglewood, Calif. The stadium, which hosts both the Rams and the Los Angeles Chargers NFL teams, also hosted Super Bowl LVI where Kroenke’s Rams beat the Cincinnati Bengals.

Another self-funded example is T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas. The home to the Vegas Golden Knights NHL team was built in 2016 for $375 million as a joint venture between MGM Resorts International and Anschutz Entertainment Group. Since 2017, the arena has hosted five Stanley Cup Finals games, capped by the Golden Knights winning the Cup there in 2023.

Later this year, the NBA’s Los Angeles Clippers’ new Intuit Dome will open south of SoFi Stadium. Its construction was privately funded by the team and its owner, former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer.

Similarly, a 2022 survey of the academic research on stadium subsidies by three former presidents of the North American Association of Sports Economists even declared that there was no more point in studying the stadium subsidy ROI question as it would only be “confirming what is already known to researchers in the field.” Authors J.C. Bradbury, Dennis Coates, and Brad R. Humphreys instead suggested that economists devote their efforts to trying to get the relevant elected officials to read that research and base their policy decisions accordingly. “The scale is already tipped heavily against the desirability of sports facility projects for improving resident welfare. Additional research seems unlikely to have a wider influence on policy making,” they concluded.

The fatal flaws in stadiums’ economic impact don’t require a Nobel Prize or formal training in sports economics to understand. While most of us think of stadiums and arenas as vibrant and bustling places because that’s what they’re like when we are there for games or concerts, the inconvenient truth is that those events are the exception, not the reality, for a stadium. Rather, they spend almost their entire lives dark and empty, coming to life for a few hours at a time then falling silent again. Some stadiums can even go for months at a time during offseasons with no major events taking place, turning them into economic black holes in a community.

But even on gamedays, stadiums are still an economic loser for local communities. That’s because common sense tells us—and the evidence confirms—that stadiums largely rearrange existing economic activity rather than generate meaningful amounts of new activity. Adding a stadium to a city doesn’t magically put more money in residents’ entertainment budgets, which means that a dollar spent at the stadium on a ticket, beer, or hot dog is a dollar not spent at some other local bar, restaurant, bowling alley, movie theater or other entertainment venue.

That creates problems when local and state governments take on new debt to fund stadium subsidies, but aren’t able to rely on increased tax revenues from economic growth to fund repayment of that debt. Thanks to federal tax law changes in the 1980s, no more than 10 percent of a tax-exempt bond’s principal and interest payments may come from revenues derived from private use of a stadium, such as team rent payments or taxes on tickets or concessions. That means that 90 percent or more of those debt payments must come from other mechanisms such as hotel and rental car taxes, Tax Increment Finance districts, broad sales taxes, and other forms of government revenue generation.

This can very quickly create very real strains on municipal budgets when promised tax revenues fail to materialize. In Cleveland, for instance, the public authority that owns the local stadiums owed the MLB and NBA teams that play there $25 million as of May 2024 for contractually mandated repairs to those two facilities after revenues from dedicated “sin taxes” on alcohol and tobacco products were lower than expected. (The repairs reportedly included such things as a $850,000 glass coating on the NBA arena to “avoid bird strikes” that will need to be replaced every five years.) Cleveland’s city and county governments, which are already on the hook for bond debt taken out over the past five years to renovate the 1990s-era facilities, will likely be forced to cover the authority’s debts out of General Fund revenues.

Public money, private negotiations

The primary reason that these factors slip past public scrutiny is that team representatives and local government officials often negotiate these deals in secret to avoid public scrutiny. In Charlotte, the city council attempted to limit public comment on the proposed $650 million in subsidies to renovate the city’s NFL stadium by holding a single budgetary meeting on the same day the deal was publicly announced. After a public outcry, the council allowed public comment at its meeting three weeks later before voting to approve the subsidy by a 7-3 margin. Independent economists estimated the deal was based on economic impact predictions that would require each fan attending games to spend roughly $1,000 more per game than they currently do, and it also requires the city to replace the stadium by 2046.

However, at least in Charlotte, those eventual revenue figures would be public records. In Kansas, proposed legislation to lure Kansas City’s football or baseball stadiums to Kansas rather than Missouri included a provision that the team’s financial reports to the Kansas Department of Revenue would be “kept confidential and if unlawfully disclosed would be subject to penalties.” The legislation would cover 75 percent of the stadiums’ costs—using a portion of sales tax revenues in the stadium district, including 100 percent of sales taxes on alcohol sales–as well as redirect lottery revenues to the project.

Punting to voters

Since 2010, voters in nine cities have been asked to approve referendums to subsidize the construction or renovation of major sports stadiums. Four were approved—in Santa Clara, CA, Arlington, TX, Oklahoma City, and Miami—while voters in Nassau (NY), San Diego, St. Louis, Tempe, and Kansas City rejected subsidy proposals.

In 2023, polling by the State Policy Network found that 79 percent of registered voters wanted a vote on major public “economic development” deals in their communities, including stadiums.

In addition to enabling bad policy decisions, this pervasive lack of transparency in the planning and negotiation process around stadium subsidies also creates an environment where corruption can flourish. Last year, former Anaheim, California Mayor Harish “Harry” Sidhu pled guilty to four federal felonies for his actions while the city was negotiating a stadium deal with the Los Angeles Angels baseball team. In a plea deal, Sidhu admitted that he passed inside information to the team’s negotiators and attempted to influence the city’s decisions in favor of the Angels in return for an expected $1 million campaign contribution from the team. (However, nobody from the team has yet faced criminal charges for their role in that deal.)

The final score

U.S. cities face the potential for a perfect storm of stadium subsidies over the next few years as the 30-year anniversaries of a generation of stadiums and arenas combine with ballooning price tags for so-called “state-of-the-art” facilities. Yet despite the clear and virtually unchallenged evidence that these deals are neither necessary nor beneficial to the communities that host them or the taxpayers who fund them, elected officials across the country continue to set new records for the biggest subsidies in history.

As sports economists Bradbury, Coates, and Humphreys noted in their definitive overview of stadium subsidy economics, we have all the research results and real-world evidence we need to say these are bad deals for our communities. The only remaining question is whether we can get our elected officials to listen before they sign deals committing taxpayers to another 30-year debt cycle in the name of being “big league.”