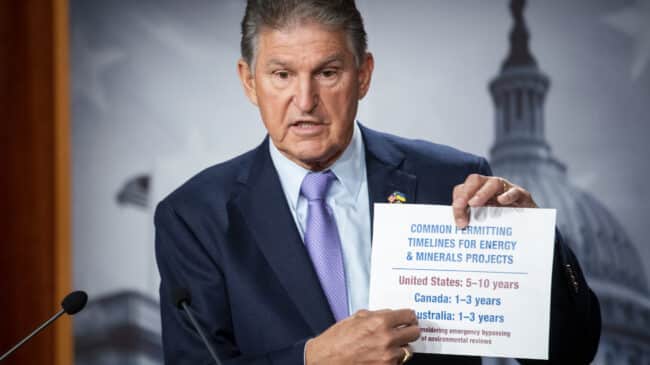

I was guardedly optimistic when Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) introduced what was portrayed as a measure to streamline the environmental review process of major infrastructure projects. This summer, Sen. Manchin had previously voted with 49 Senate Republicans to overturn a Biden administration action that scrapped modest 2020 Trump administration environmental streamlining, but that measure died in the House. The Associated Press reported:

Manchin countered that, “for years, I’ve worked to fix our broken permitting system, and I know the (Biden) administration’s approach to permitting is dead wrong.″

Manchin called Thursday’s vote “a step in the right direction” but said the measure likely “is dead on arrival in the House. That’s why I fought so hard to secure a commitment (from Democratic leaders) on bipartisan permitting reform, which is the only way we’re going to actually fix this problem.″

Manchin thought he had bipartisan support for the permitting reform bill he refers to, but Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) whipped Republican votes against the bill, causing Manchin to pull it.

While Manchin’s bill would’ve delivered some incremental progress on permitting, it was far from the thorough reforms needed. Over the past two years, we’ve seen a growing number of studies comparing the very high costs of major U.S. infrastructure projects with comparable projects in Europe and Japan. Like the United States, these countries also all have environmental laws that infrastructure projects must comply with, but studies show Italy and France can build new subways faster and for about half the costs per mile as U.S. subway projects. This suggests something is seriously wrong with America’s environmental review process.

A significant factor identified by researchers as driving the higher costs is the massive role of the “citizen voice” in the review process for U.S. projects. Frequently cited on this topic is a 2019 study by George Washington University’s Leah Brooks and Yale University’s Zachary Liscow, which sought to explain why the cost per mile of building U.S. Interstate highways tripled between the 1960s and 1980s.

Citizen litigation to prevent or redesign highways came about not via the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1970. The key factor was a 1971 Supreme Court ruling—Citizens to Protect Overland Park v. Volpe—that citizens could sue administrative agencies over environmental impacts. Brooks and Liscow estimate that citizen voice litigation is a significant factor in forcing expensive design and location changes that helped cause the tripling of per-mile costs in the United States.

A growing number of liberal and centrist critics have recently published articles lamenting the obstacles to needed infrastructure imposed by the “citizen voice” in this country. They include Ezra Klein in The New York Times, Jerusalem Demsas in The Atlantic, Matthew Yglesias in his Substack newsletter, and many others.

Construction unions have also picked up on this problem, such as this comment by James T. Callahan, president of the International Union of Operating Engineers:

“Since its modest beginnings, NEPA has evolved into a massive edifice, capable of destroying project after project, job after job, in virtually every sector of the economy. Dilatory strategies employed by project opponents frequently exploit provisions in NEPA, weighing down projects, frustrating communities, and raising costs to the point that many applicants, whether public or private, simply walk away.”

Sen. Manchin’s well-meaning bill pretty much ignored this major problem. It included a statute of limitations for court challenges, maximum timelines of two years for NEPA reviews, and an “improved process” for categorical exclusions under NEPA. But there was nothing that would overturn numerous court decisions that have empowered citizen litigation.

Another problem is that Manchin’s measure was limited to energy projects. Highway and mass transit projects are also generally subjected to endless citizen litigation. A more consequential bipartisan reform aimed at getting needed infrastructure projects approved more efficiently would have to include all infrastructure categories.

Another major problem was the bill’s reliance on “administrative earmarking.” Had the bill passed, it would have directed the president to “designate and periodically update a list of at least 25 high-priority energy infrastructure projects and prioritize permitting for these projects.” This would be a recipe for high-powered lobbying for projects that might fail a benefit/cost analysis but could offer lucrative contracts for companies and unions. Earmarking is earmarking, whether done by the legislative or executive branches of government, and it plays a harmful role in politicizing the infrastructure project selection process.

The U.S. needs meaningful permitting reform. The country seems primed for a broad, centrist coalition that recognizes the need to build and modernize infrastructure and supports streamlining environmental reviews of energy and transportation projects. This potential coalition could include supporters of highway expansion in fast-growing states, mass transit projects in dense urban areas, wind and solar projects in blue states, and natural gas and nuclear projects in red states.

Basic statutes such as the National Environmental Policy Act and the Clean Air Act would likely not be subject to change. Instead, the focus of the reform effort would be on curtailing the extent of citizen litigation, drawing on the lessons being learned by research done by entities like the New York University Marron Institute’s Transit Cost Project and similar work from the Eno Center for Transportation.

I am not aware of specific reform measures that would adequately address this problem, so considerable work must be done. Part of the answer might be challenging key court decisions that have empowered citizen litigation. An important element would be specific federal policy changes for Congress to enact.

A diverse group of research organizations, such as the American Enterprise Institute, Bipartisan Policy Center, Breakthrough Institute, Brookings Institution, Hoover Institution, and Reason Foundation, along with the above-noted Eno Center and Marron Institute, could play valuable roles in these types of issues.

If reform proposals are developed, energy and transportation organizations should also mobilize to support legislation to implement the recommendations. In the transportation sector, I’m thinking of groups like the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, the American Road and Transportation Builders Association, the Associated General Contractors, and others, along with construction trade organizations and other unions.

With infrastructure construction costs escalating at a much faster rate than the Consumer Price Index, there’s a real danger that the increased federal funding in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, also known as the bipartisan infrastructure bill of 2021, could fail to lead to much actual expansion of infrastructure—unless there is meaningful streamlining of the environmental, permitting and litigation process.

While Sen. Manchin’s bill didn’t address many of the critical problems and ultimately failed, it is notable that there’s a growing coalition that recognizes that policy reforms are needed to address the excessive obstacles blocking key infrastructure projects. Centrists in both major political parties acknowledge that needless delays, bureaucracy, and litigation are increasing taxpayers’ costs and preventing the U.S. from modernizing and building 21st-century energy projects, highways, mass transit, and more housing. Now, researchers and Congress need to develop substantive policy and legislative solutions to start removing obstacles and addressing them so the country can build the infrastructure it needs.

A version of this column originally appeared in Public Works Financing.