The Oregon state legislature passed a series of reforms to the Oregon Public Employees Retirement System (OPERS) aimed at shielding its public employers from a hike in pension contributions, primarily by diverting employee contributions into the system. While the changes should help reduce costs to employers in the short-term, they come at the price of higher overall costs in the long-term. Furthermore, the reform introduces several changes with potential impacts on retirement security for public employees.

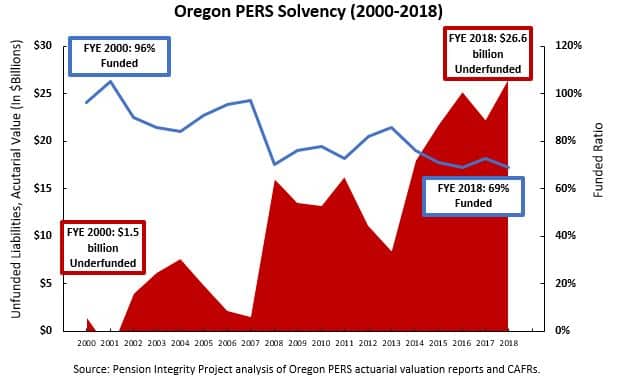

Senate Bill 1049, awaiting final signature from Oregon Gov. Kate Brown, is expected to save between $1.2 and $1.8 billion in employer contributions each biennium until 2035. Of those savings, 66 percent is to come from extending the amortization period of the plan’s estimated $26.6 billion unfunded actuarial liability (UAL) by 6-8 years. OPERS’ largest unfunded liabilities currently have between 14 and 16 years left on their debt payment schedule. This bill would combine those liabilities and extend the new debt payment schedule out to 22 years. This essentially underfunds the pension system by refinancing the growing pension debt over a longer period, saving money now at the cost of paying more in the long run.

The bill also redirects a portion of what members currently contribute to the Individual Account Program (IAP)—the defined contribution plan component of Oregon’s hybrid retirement plan—instead shifting some of that amount into a newly established Employee Pension Stability Account (EPSA). The EPSA balance will be used to offset pension contributions that would otherwise be required from employers. The practical impact of this change is that OPERS members will now be contributing to the defined benefit portion of their pension, but at the cost of a 7-12 percent cut to their estimated final IAP balance. Employees making under $30,000 annually are unaffected by this change and will have no redirection away from the IAP.

The redirect percentage is based on which of the three tiers the employee belongs in. All three tiers currently contribute 6 percent of pay to the IAP. More senior employees, who are in the generous OPERS Tiers one and two, will have 2.5 percent of their contributions redirected. Tier three members, who make up 68 percent of OPERS active employees, will have 0.75 percent of their contributions redirected. Once the plan reaches 90 percent funded the redirect will cease, and members’ contributions will fully go towards their IAP again. This change accounts for 20 percent of the bill’s cost savings.

Two smaller changes in SB 1049 account for the remaining 14 percent of savings. First, the rules around employees collecting additional pension credits after retirement will be tightened. For the next 5 years, employees will no longer accrue additional OPERS service credits while receiving a pension. Additionally, the employer contributions that would have gone towards paying for that employee’s accruing benefit would instead be credited to an employer account to help pay down the plan’s unfunded liabilities.

Second, a final average salary (FAS) cap of $195,000 will be applied to the retirement formula for all prospective hires. This change would eliminate any future retiree in OPERS from receiving upwards of $500,000 a year in pension benefits as some current retirees do.

The bill also includes a one-time $100-million transfer from the general fund and an agreement with the state that 80 percent of any potential sports-betting revenues would go to help pay down unfunded pension liabilities.

OPERS Contribution Structure

Before further analysis of the bill, it’s important to first discuss the history of employer and employee contributions into PERS.

Prior to 1979, OPERS members shared the costs of their defined benefit (DB) pension plan by way of a 6 percent employee contribution rate. Then in 1979, the Oregon legislature, during a period of statewide revenue shortages, made an allowance for any OPERS participating employer to pay the entire 6 percent employee contribution, which is now referred to as the “pick-up,” in lieu of granting raises to employees. Employees who had their contributions “picked-up” effectively took home an extra 6 percent of pay with this change. Oregon voters attempted to eliminate this “pick-up” option by ballot measure in 1994 but were rebuffed when the measure was overturned by the Oregon Supreme Court.

In 2003, the state implemented pension reform by opening a Tier 3 hybrid plan, the Oregon Public Service Retirement Plan (OPSRP), combining a smaller traditional pension benefit with the IAP defined contribution plan. Employee contributions, whether “picked-up” or made by the employees themselves, now went into the IAP for all three tiers.

By 2016, the Legislative Fiscal Office of Oregon estimated that 72 percent of all PERS-eligible employees still received this “pick-up” of their contributions. Not only is that 6 percent fulfilled by their employers, but it is also considered salary as it relates to the pension formula for the more expensive Tier one and two members. It took until 2019 for this “pick-up” to be fully eliminated, by way of bargaining with public employee unions to get a one-time 6.95 percent raise, constituting 6 percent to cover what employees would now be paying into their own IAP and an additional 0.95 percent to cover payroll taxes.

Analysis and Impacts

Here are several changes with potential impacts on retirement security:

1. Extending out the unfunded actuarial liabilities (UAL) amortization schedule will delay the plan reaching 100 percent funded status by 6 years.

OPERS is taking a massive hit to its solvency by extending its debt payment schedule by 6-to-8 years. This bill does give employers sought-after contribution rate relief, but they are already receiving a $1.6 billion break on their contributions this biennium due to collars the OPERS board places on biennia-over-biennia contribution rate increases. The extension of Oregon’s pension debt payment schedule will increase the risk that unfunded liabilities will grow in the future. The longer that unfunded liabilities are on the books, the greater the risk of assumptions missing their targets. If assumptions miss their targets, then the next generation will be paying for the liabilities of this generation of workers and retirees through increased contribution rates.

Further, OPERS is currently scheduled to have its debt paid off and reach full funding in 2035, but with the changes in SB 1049, the plan will still be under 90 percent funded by then. Much like Gov. Brown’s task force on addressing the state’s pension shortfalls, this bill doesn’t address the growing pension debt in the first place, nor does it provide solutions to prevent further increases to it.

2. The OPERS reform presents a more mixed and uncertain bag for employees.

The employees’ trade-off for taking a 7-12 percent hit on their IAP is more direct control on investments within individual account plans (IAP), instead of the current policy of having only one IAP investment option (target date funds). SB 1049’s contribution redirect until OPERS is 90 percent funded also puts members in a position where they will be losing out on contributions into their IAP, and the investment growth of those contributions, over a longer timeframe.

3. The entire point of opening a Tier 3 in 2003 was to mimic successful hybrid plans across the country.

The hybrid model Oregon is trying to emulate is built with the goal of sharing risk between the employee and the employer. This is done by the employer contributing to a modest pension benefit, and the member contributing to a defined contribution (DC) benefit. OPSRP is no different. It was designed for the pension to provide approximately 45 percent of a member’s final average salary at retirement (for general service members with a 30-year career) and the IAP portion was estimated (using an overzealous 8 percent return assumption) to provide an extra 15-20 percent of a member’s FAS. This arrangement would net a career employee with a replacement ratio of 60-65 percent of their FAS in retirement. Leaning on redirected member contributions to bail out the employer-provided DB portion of a hybrid plan goes against its basic funding principles.

4. By giving PERS employees a 6.95 percent raise to offset the loss of the “pick-up,” the legislature has effectively increased the plan’s payroll for contribution rate setting purposes.

This allows PERS to collect more dollars than when the employer “picked-up” the contribution, because the contribution percentage will be based on a 6.95 percent higher salary for each employee. It’s worth noting that this is one of the few changes that has some upside for employees in SB 1049. They may be contributing more real dollars due to their higher salaries, but their take home pay will be unaffected, and an increased salary will bolster their final average salary in the retirement formula.

Conclusion

SB 1049 introduces an array of changes for plan stakeholders:

- Employees – Lose out on 7-12 percent of their final IAP balance, but this could be somewhat offset by growth in salary affecting their pension calculation. Overall a net negative.

- Employers – Gain short term budget flexibility with the extension of the amortization period but will end up paying more, for longer, in the future to pay down the current debt. Overall a net budgetary positive in the short term but turning negative in the long run when considering the higher resulting costs and longer risk exposure.

- OPERS – Extension of the amortization period puts the plan at further risk of insolvency, and puts more pressure on the assumptions, namely investment return, being accurate. OPERS underfunded status will be extended with the bill’s changes. Bill contributes a lump sum to help pay down UAL costs, and will grant sports betting revenues to the OPERS unfunded liability. Overall a net negative on plan solvency.

The most recent legislative attempt at reform, which cut retiree Cost of Living Adjustments (COLAs), resulted in a lawsuit. That lawsuit made its way to the Oregon Supreme Court, with the retiree groups seizing victory in 2015. Statements from labor concerning SB 1049 hint that another battle in the courts could materialize.

Another legal battle would be unfortunate because the sooner all stakeholders come back to make meaningful changes to PERS, the better. If SB 1049 is signed by Gov. Brown, the legislature has made the decision that some short-term budget flexibility is worth the trade-off of adding more risk into OPERS and deteriorating its already weakening solvency.