With states now projecting massive reductions in tax revenues for education due to lost economic activity during COVID-19 shutdowns (some as high as 20 percent), the federal government is debating another phase of stimulus funding in hopes of lessening the financial blow. Even after trillions of dollars in pandemic relief and stimulus spending, which included tens of billions of dollars in additional education aid—some advocates are calling for as much as $200 billion in additional education spending—some states will likely still have to implement dramatic fiscal austerity measures to balance their education budgets in the coming years. And while this federal aid may ease some of the burden on state finances, it also comes with significant risks. If the federal government is going to consider adding to the nation’s already-massive public debt load, it’s important that policymakers learn from past mistakes and ensure that education dollars are allocated effectively, that they don’t simply layer more money on top of existing problems in state school finance systems, and allow for ample flexibility so that local school leaders are in the driving seat for spending the money.

A good first step for policymakers today is to evaluate the federal education stimulus package under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009. Faced with economic devastation under the Great Recession, Congress signed this law providing more than $100 billion additional dollars in aid to state education systems. It is especially critical to consider how this package was structured, including the formulas by which dollars were allocated to states, school districts, and schools.

Understanding ARRA Education Funding

ARRA’s $100 billion in additional federal funding for education operated under four primary principles:

- Spend funds quickly to save and create jobs.

- Improve student achievement through school improvement and reform.

- Ensure transparency, reporting, and accountability.

- Invest one-time ARRA funds thoughtfully to minimize the “funding cliff.”

The bulk of ARRA education dollars were distributed as three major pots of funds that were available for only two to three years.

The first—and the largest share—was the State Fiscal Stabilization Fund (SFSF). Totaling $48.6 billion, these funds were allocated directly to state governors primarily based on the number of K-12 students in their public-school systems. While governors were given some flexibility over the dollars, they were obligated to direct the bulk of the funds toward early childhood education, K-12, and higher education (with $39.8 billion nationwide ultimately spent on this purpose). After governors could demonstrate that main education needs were met, the remaining funds were used for education-related supports like school facilities, public safety, and other government services (amounting to $8.8 billion nationwide). And finally, the last component of the SFSF was $5 billion in competitive grants for “Race to the Top” programs, a federally sponsored and statewide program meant to improve student achievement.

The next major funding category was $10 billion in additional funding for Title I, Part A. This is a federal program meant to provide additional support for low-income students and it is subject to several main restrictions. Namely, the funds must “supplement, not supplant” existing state funds, and states must demonstrate that they are continuing their commitment to funding education by meeting “maintenance of effort” requirements. Moreover, in schools not classified as Title I schools—meaning that less than 40 percent of their students are low-income—the funds must be spent on the students most at risk of failing. In schools that are classified as Title I schools—meaning that 40 percent or more are poor—schools have additional flexibilities to operate schoolwide Title I programs, provided that they are still intended to improve the achievement of lower-performing students.

The third funding pot was $11.7 billion for Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Part B. Also subject to “supplement-not-supplant” and “maintenance of effort” provisions, these are funds intended to pay for services for students with diagnosed disabilities and who are learning under Individualized Education Plans. It’s important to note that the ARRA funds for Title I and IDEA were resources over and above those already provided on an annual basis by the federal government—roughly doubling funding for these programs temporarily.

Primary Problems With ARRA Funding

This analysis will focus primarily on SFSF funds, since they were the largest funding pot and were intended to provide relief for general education budgets. It’s important to recognize that the SFSF provided some modest relief insofar as its immediate objectives were concerned—namely, temporarily preserving jobs for school employees. Moreover, the bulk of the funding delivered via the SFSF (the $39.8 billion) allowed governors some limited flexibility over how resources could be used. But there are other lenses through which the stimulus program can be evaluated that highlight some major problems.

Problematic Variation in State Distribution Practices

While governors were given some discretions, the ARRA statute was overly vague in how it required state leaders to allocate SFSF funds, and ultimately boxed their decision-making in as they tried to comply with federal guidance. While the statute specified that 81.8 percent of the SFSF funds must go to early, K-12, and higher education and further required that these dollars be allocated via the state’s “primary elementary and secondary funding formulae,” governors were generally free to determine what these primary formulae were.

Texas, for instance, allocated $1.38 billion of its $3.25 billion in SFSF dollars via their Permanent School Fund, rather than placing those dollars in their main formula. The Permanent School Fund is a large public investment fund with a current balance of around $46 billion, a small portion of which (not to exceed 6 percent of the fund balance) is allocated to school districts each year. The state’s constitution requires that 50 percent of disbursed funds must be devoted to instructional materials, and the remainder is allocated via a flat, per-pupil rate. This is a far less equitable use of ARRA’s SFSF dollars because, unlike Texas’ main formula which equalizes funding, these dollars are diverted to property-wealthy districts that sometimes spend substantially more and have less demonstrated need.

As another example, North Carolina broadly defined its “primary formulae” in such a way that it included categorical program funding for items like professional development, driver training for ninth-graders, and gifted and talented education. This is because, unlike most states, North Carolina allocates funding based on resources and programs rather than students. One reason this is problematic is that staffing positions are doled out in such a way that school districts with more tenured staff—which also tend to be more affluent school districts—get a disproportionate share of resources. Thus the state distributed a large bulk of its ARRA funds via mechanisms that aren’t directly based on overall student counts or student needs and ineffectively account for districts’ abilities to raise local enrichment dollars.

This wide divergence around which mechanisms states were allowed to use to distribute stimulus funds—as enabled by both the ARRA statute and by different state funding practices—generated scenarios where dollars were often divided unfairly through flawed formulas.

General Lack of Consideration for Existing Funding Disparities

Beyond the vagueness of the statute governing how SFSF funds were to be allocated by governors, the ARRA bill also didn’t provide guardrails to ensure that dollars were targeted to the highest-need districts and those that were hit hardest by the 2009 recession. In fact, the statute only directed states to consider how they were dividing up state resources and did not require that they take existing local resources into account when delivering the funds. This meant that the stimulus resources were either indifferent to or even exacerbated existing funding gaps caused by an unfair state funding system.

Consider another example. Unlike Texas, Missouri put most of its SFSF funds for K-12 into its main funding formula. However, the state’s funding system has a lot of flaws, including hold harmless provisions that subsidize already well-resourced school districts, outside categorical grants that undermine the equity of the main formula, and generous allowances for districts to raise non-equalized local revenues based on their property wealth. Consequently, there are large disparities in per-pupil funding across Missouri whereby property-rich districts tend to get significantly higher resources, and disadvantaged students too often receive less support.

One way of evaluating ARRA funding patterns in Missouri is to consider how much of this funding went to the highest-spending, lowest-poverty districts. To do this we separated all the state’s school districts into two quartile groups based on per-pupil spending and poverty rates. Then we isolated 42 districts that fall into both the highest-spending quartile and the lowest-poverty quartile, and found that these school districts siphoned off about $133.7 million in stimulus funds from higher-need districts, accounting for about 10 percent of the state’s total ARRA spending. One reason for this is because Missouri’s main formula only accounts for a proportion of the overall education budget, failing to capture how resources are distributed to districts by other revenue streams. Problematically, this means that low-need property-wealthy school districts that already had high funding levels from excess local revenues, hold harmless provisions, and categorical grants still received ARRA funds, illustrating how at least a portion of stimulus funding was allocated in a manner that lacked fairness and strategic purpose.

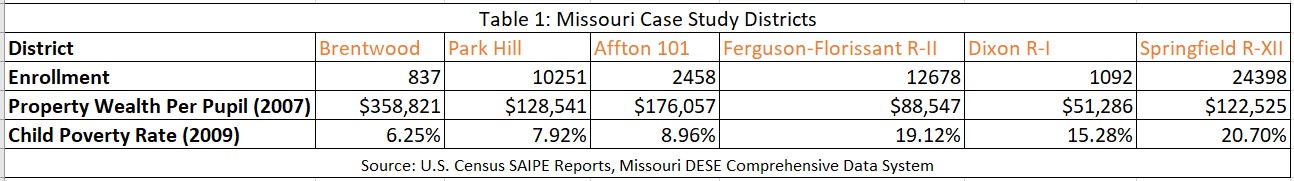

Another case study example from Missouri is to consider specific districts. Here’s a small group of school districts in the state that vary widely on property wealth and poverty levels:

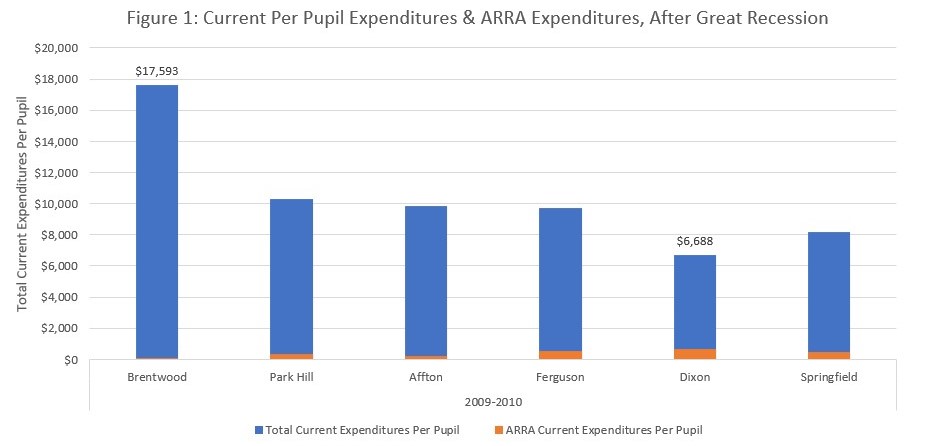

Next, look at their current expenditures per pupil (expenditures for daily operations) right after the Great Recession, and how ARRA funds factored into their comparative funding levels in the first year. Note that the ARRA figures include spending from both the SFSF and the supplemental Title I and IDEA funds:

Source: National Center for Education Statistics F-33 Reports

There are a few important problems illustrated by Figure 1. The most prominent issue is the large per-pupil spending disparities across each district. It’s particularly striking how these disparities are closely positively correlated with property wealth levels and generally negatively correlated to poverty rates (based on Table 1).

A second key point is to understand that these funds were ultimately a very small proportion of each school district’s annual budget. Consequently—even though ARRA dollars were somewhat targeted to higher-need school districts—these funds had very marginal effects on overall funding fairness.

Issues With ARRA Title I and IDEA Grants

As explained earlier, the stimulus funds for Title I, Part A and IDEA, Part B were—in contrast with the SFSF grants—subject to well-established restrictions in service of low-income and special education students. Importantly, these dollars also were not directly intended to offset losses in general fund revenues like the SFSF funds were but were instead intended to provide further protections for disadvantaged students who were most vulnerable to the recession.

Federal dollars generally account for only 10 percent of a typical state’s education budget. Nonetheless, these dollars still come with restrictions meant to ensure both that states don’t treat them as fungible resources and that they are spent on the intended student groups. However, policymakers are increasingly recognizing that categorical restrictions on funding often undermine the effectiveness of those dollars. When resources are especially scarce, a lack of flexibility over funds—as well as the administrative costs of demonstrating compliance—are often counterproductive. In a survey of school district administrators on how they were using ARRA funds, one official lamented:

“Requiring districts to spend funds within the guidelines of Title I and IDEA severely restricted our flexibility and effectively prevented us from ‘stimulating’ the economy. We have money for federal programs. What we are missing is money for regular education, smaller class sizes, adequate salaries to attract quality teachers and administrators, and general support for the basics of providing a school.”

These federal dollars also weren’t allocated fairly. For instance, the $10 billion in ARRA funding for Title I—which is typically administered with four separate funding formulas—was allocated using only two of the four formulas. One of them, the Education Finance Incentive Grant (EFIG), provides additional funding to states that have more equitable funding systems and that devote higher shares of per-capita income to education. The other formula, Targeted Grants, is meant to provide funds to districts that have relatively high populations of poor students relative to other districts in their state.

While these formulas are deeply complex, the main problem is that they make context-based adjustments that fund low-income students unfairly based on factors that are outside of their control. For instance, EFIG’s ‘effort’ component fails to account for factors such as tax revenue, which might limit a state’s ability to devote additional dollars to education. As a result, the final EFIG allocations in 2015 ranged from a low of $219 per formula-eligible child in Idaho to $684 per formula-eligible child in Vermont. In the same year, the Targeted Grant allocation had a gap of $481 per formula-eligible child between these states.

When considering both the temporary nature of this pot of ARRA funds and the fact that they weren’t directly intended to supplant lost state resources, it should come as no surprise that states struggled to identify ways to effectively and sustainably use these funds. When school district leaders were surveyed on their use of ARRA Title I and IDEA funds, they indicated that the most popular use was professional development (63 percent Title I/68 percent IDEA), followed by saving personnel positions (58 percent/61 percent), classroom technology (53 percent/54 percent), classroom equipment/supplies (38 percent/41 percent) and software (35 percent/37 percent).

Delayed Fiscal Cliffs and Ineffective Spending

Because of their large expense, ARRA funds could only be temporary. While having these funds available in the immediate aftermath of the Great Recession played some role in smoothing out fiscal cliffs experienced by states, they also simply delayed some of the necessary cuts to state budgets. Current expenditure data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) show that while ARRA funds and other state-level funding adjustments kept nationwide per-pupil expenditures relatively flat compared to pre-recession spending in the 2009-2010 and 2010-2011 school years, these spending levels subsequently decreased in the 2011-2012 school year and hit post-recession lows in 2012-2013. This is because many state economic recoveries were moving slowly, and further because state revenue growth tends to lag behind economic growth.

Consequently, much of the ARRA funding was used in ways that likely didn’t make a significant direct impact on students. While the most common use of SFSF funds—reported by 52 percent of survey district leaders—was saving personnel, these salvaged jobs didn’t last in many cases. Similar to the Title I and IDEA resources, other popular uses of the SFSF funds included professional development (mentioned by 28 percent of respondents), classroom technology (23 percent), and supplies and school maintenance (17 and 12 percent, respectively).

It’s important to note that states that refrained from shoring as many job losses as possible weren’t necessarily making a bad policy decision. Although some of the main ARRA principles of pushing states to minimize fiscal cliffs and invest stimulus dollars sustainably were good policy goals, they were often at tension with one another. States and school districts understood they couldn’t rely on the federal stimulus money over the long-run, and they also likely knew they couldn’t count on local and state revenues to rebound by the time stimulus funds dried up.

Conclusion

From a very narrow perspective, ARRA succeeded in smoothing out some of the hardest strains on state budgets. But stepping back, it’s clear that federal policymakers’ survival-mode approach produced a massively expensive program that ultimately did little to remedy the growing spending disparities in states. ARRA was overly-committed to existing federal programs that have often failed disadvantaged students, and thus the stimulus spending couldn’t strike the right balance between fairness and flexibility.

The shortcomings of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act’s education component demonstrate that, even when education stimulus programs receive substantial appropriations and have some laudable governing principles, they can be undermined by their own transience and by the poor funding formulas of states themselves.

As Congress considers strategies for education relief packages during the coronavirus pandemic, these hard lessons should be at the forefront of their thinking.