A standard line in the punditry circuit this week has suggested that Mitt Romney’s selection of Paul Ryan as his running mate will bring a welcome measure of substance to the race. If so, then cheers all around. Hopefully, one critical element of the economy and society that has gotten little substantive attention to date will get its due: housing finance and property markets. In principle, a Romney-Ryan Administration should represent a significant break from what President Obama has done in his first term on housing policy.

President Obama has tried a number of programs to address the struggling housing market, including the Making Home Affordable programs to refinance mortgages and use taxpayer funds to pay banks to write down principal. Neither Romney nor Ryan has been very vocal about these programs in detailing how they have backlogged the foreclosure process, thus hurting homeowners and dragging out the price decline timeline. And neither has used their platforms to point out how these programs served as a back door bailout to banks by encouraging trial mortgage modifications that were never designed to succeed; instead implemented to simply delay when banks had to register losses on their balance sheets to soften the blow to earnings.

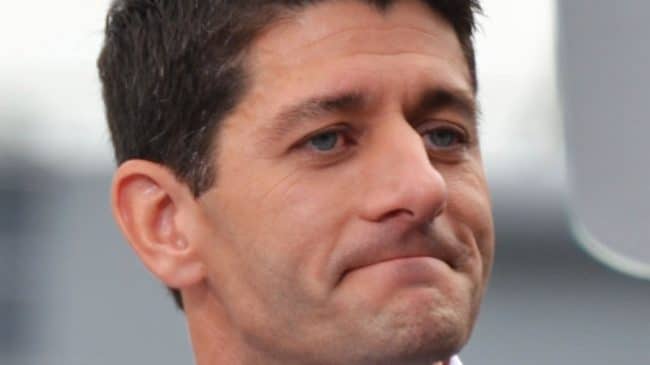

However, on the campaign trail, Romney has said that he thinks the best way to address the housing problem is to let foreclosures process through and let prices bottom out. So a Romney-Ryan administration would be likely wind down these programs and take a new approach. But what would this new approach look like? Moreover, what does Ryan’s ascendance to the ticket bring in terms of substantive discussion on new approaches to housing finance and property markets in the presidential race?

Looking at housing finance, Romney and Ryan have been similarly vague on reforming the role of Wall Street in homeowners’ lives. Ryan has raised questions about allowing banks to become so big they need taxpayers to bail them out if they begin to fail. Many have suggested Ryan’s comments imply support for breaking up the big banks. On the other hand, Ryan is an ardent critic of the Dodd-Frank regulatory reform bill and has advocated for limiting the federal government’s ability to take over and dismantle failing financial institutions – no matter how beneficial such an outcome might be.

Most of the attention has focused, understandably, on Ryan’s tenure as the conservative point man in Congress on the federal budget. And while discussions of spending priorities and entitlement reform paths are valid discussions on their own, they also frame important questions like how to bring market forces back to housing.

Unfortunately, a brief pass through the Ryan budget turns up little commentary on the future of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the proverbial 800 pound guerrillas in the housing finance room. The two mortgage giants, taken into conservatorship in August 2008, are now essentially wards of the state. They continue to draw taxpayer money from the Federal Reserve to cover their losses and, with around $5 trillion in mortgage-related liabilities, some accounting methods would ascribe those as potential losses to the taxpayers. The Ryan budget does not account for them when considering a baseline, nor does his plan give many details about ending the ongoing bailout beyond loose acknowledgement of a bill from Rep. Jeb Hensarling (R-TX).

How to stop a bailout that has blown past $200 billion from continuing to grow is certainly something a budget focused leader – like Ryan – should be pushing his party to address, and that a presidential candidate – like Romney – should articulate as part of a main message to the public that Washington is wasting too much money. Yet, Ryan has done little publicly to support efforts in the House Financial Services Committee to advance the cause of ending the government-sponsored enterprises (GSE), or advancing ideas that could help restore housing finance. And unfortunately his budget is not much different from Obama’s budget relative to the scope of irresponsible spending and entitlement problems.

At most, Romney economic plans offer a paragraph to say he’ll address the GSE issue, though without details suggesting how. Here it’s certainly true that many good ideas have been floated (see Reason Foundation’s paper “Restoring Trust in Mortgage-Backed Securities” by Mark Joffe and Anthony Randazzo for a list of recommendations), and even introduced as legislation in the House.

The Obama campaign is similarly guilty of limiting the substantive discussion of housing finance, the GSEs, and restoring the mortgage-backed securities market (including both the questions of how and whether it should even be done).

The separation between Romney-Ryan and Obama-Biden is in the intellectual traditions they claim to support, particularly on tax policy.

Both Romney and Ryan have argued for a streamlined tax code with a broader base that allows for tax rates to be lowered overall. Ryan has consistently argued for a system in which markets sort out which private institutions fail and which ones thrive. Romney, a successful product of the private investment community, recognizes the inherent if sometimes traumatic value of an economy that creates value through profit and loss. Indeed, this was the bedrock bet of companies like Bain Capital that specialized in identifying undervalued assets and bringing them back to profitability.

We know from the first term of the Obama administration what their approach to housing policy would be in a second term. As for Romney/Ryan, unfortunately the record of substance thus far from their camp has been rather underwhelming. Nevertheless, what would be the implications of taking the pro-growth, pro-investment framework for economic policy the GOP purportedly supports and using it to guide policy for property markets and housing finance?

First, we would expect to see reforms that reduce distortion in housing markets. Tax loopholes and targeted tax incentives are likely to have a rough road in a Romney-Ryan administration. Corporate tax deductions and investment tax credits are likely to become targets as fiscal conservatives look for ways to lower overall tax rates without appearing like they are sops for the well healed. This may well translate into a critique and rolling back of the home mortgage tax deduction, particularly since research shows the benefits accrue mainly to the wealthy while having little impact on the overall health of the housing market.

Second, there could be fewer attempts to use government programs to fix the housing market. Ryan infamously voted for the Toxic Asset Relief Program (TARP); admittedly going against his core principles. But the intellectual tradition Romney and Ryan are defending would arguably reject this path in the future. A hard landing is better than a prolonged, drawn out, soft economy incapable of creating the jobs necessary to keep Americans financially solvent and independent. And Romney has said, accurately, that the best thing for the housing market is a hard landing and letting the market clear out toxic debt before things get better.

Bringing substantive ideas to the debate and challenging the Obama administration on its poor housing record would be the “substance” pundits are predicting from the new VP nominee. However, in order to accomplish this, Romney and Ryan will need to sketch out more detailed plans for how they will approach the housing mess if they want there to be a real debate. Otherwise, their record suggests their approach to the struggling housing market will either be to ignore the problem or follow loosely in the path of the Obama administration.

Samuel R. Staley, Ph.D. is a senior research fellow at Reason Foundation and Managing Director of the DeVoe L. Moore Center at Florida State University. Anthony Randazzo is director of economic research at Reason Foundation.