The country’s rapidly aging population is expected to increase demand for health care services in the coming years, and current trends suggest there will be a physician shortage that makes it difficult to keep up with medical needs in the United States. The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted this problem and prompted the federal government and many states to implement emergency measures to prevent health care providers from suffering pandemic-related staffing shortages. These temporary efforts are encouraging, but permanent reforms are necessary.

A recent bipartisan proposal in Congress would allow more foreign health care workers to immigrate to the US to help combat the pandemic. The Healthcare Workforce Resilience Act (HWRA) would recapture up to 40,000 unused employment-based immigrant visas from prior years and allocate them to physicians and nurses. Specifically, the legislation would reserve 25,000 visas for nurses and 15,000 for physicians. The visas issued under the legislation would not be subject to any per-country numerical caps, and additional visas would be made available for spouses and unmarried children of the health care workers. Prospective recipients could petition for the visas up to 90 days after the end of the COVID-19 national emergency declaration. Temporary measures like the HWRA would be beneficial, but America’s aging population will result in physician shortages well beyond the pandemic, and permanent solutions are needed.

America’s Looming Physician Shortage

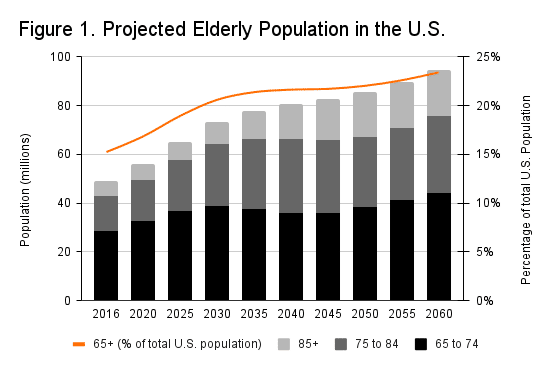

According to projections from the Census Bureau, the population of people over the age of 75 will more than double in the next 40 years. Figure 1 below shows that over the same period, the population of people over 85 is expected to nearly triple.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau Population Projections

Meanwhile, approximately 32 percent of physicians in the United States are already over the age of 60, and 51 percent of physicians are between the ages of 40 and 59. The median retirement age among physicians is about 65- years old, which suggests that a large share of America’s physician workforce is likely to think about retiring over the next decade.

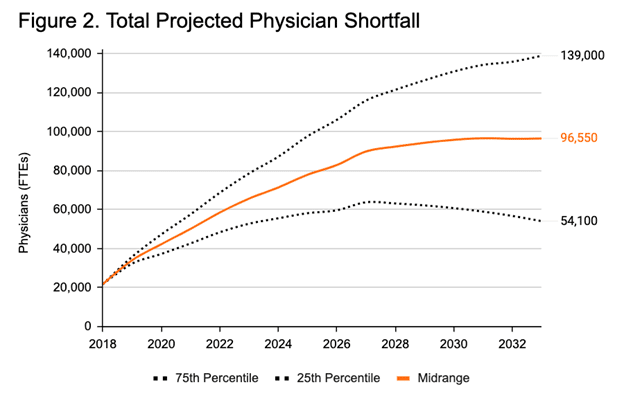

The number of new health care workers entering the workforce may not be sufficient to offset the combined effects of the aging population and anticipated physician retirements. Figure 2 shows recent projections from the Association of American Medical Colleges suggesting the US could face a shortage of between 54,100 and 139,000 physicians by 2033. Allowing more foreign-trained physicians to practice in the United States could help alleviate this shortage.

Source: Association of American Medical Colleges

The Role of Foreign Medical Graduates

Immigrant physicians and nurses already play a significant role in the country’s health care workforce. A recent Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) report found that approximately 30 percent of physicians in the United States were foreign-born. However, it can be difficult for more foreign-born physicians to come to the US and practice medicine, especially if they received their training in other countries.

Data limitations make it difficult to assess how many health care workers in each occupation arrive annually under various visa programs. However, the available data suggest that the US immigration system does not prioritize health care workers. For example, a report from the Migration Policy Institute stated that:

“Just 5 percent (or 4,771) of the 93,615 H-1B petitions approved for initial employment in fiscal year (FY) 2018 went to workers in occupations in health care and medicine, according to Department of Homeland Security (DHS) data. Fifty-one percent of annual H-1B petitions in FY 2018 went to workers in computer-related occupations.”

Expanding immigration opportunities for physicians would likely be beneficial given the anticipated shortage. However, doing so within the current immigration system would involve difficult tradeoffs and disadvantage other occupations. The challenge is that workforce needs and priorities vary across states. Some states may, in fact, benefit more from workers in tech-related occupations than from physicians.

One solution to this problem is to grant states additional authority to determine their own immigration priorities based on their own workforce demands. Canada and Australia have implemented similar regional immigration programs that could serve as models.

Navigating limited immigration channels is only part of the problem. Foreign medical graduates (FMGs) must also obtain state-level licenses to practice medicine in the United States. Education requirements in the US are different than in most other developed countries, so FMGs often need to receive additional education and training––even if they have substantial experience working abroad.

Licensing requirements for foreign medical graduates can vary considerably from state to state. In general, FMGs are required to pass multiple exams, demonstrate English-language proficiency, obtain sub-specialty certifications, and complete a residency program in the US or Canada. If they wish to meet their residency requirement in the US, they must clear additional hurdles along the way. As the American Immigration Council explains:

“First, the Educational Commission on Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) must certify that the foreign national is academically prepared to enter a U.S. graduate medical education program (residency). Then, the physician must “match” into a U.S. residency program, in competition with U.S. medical graduates as well as other international peers.”

Residency program requirements can create significant bottlenecks for foreign medical graduates. In many cases, FMGs who completed residencies in other countries are required to repeat them because states may not recognize residency requirements in those countries. Moreover, match rates are considerably lower for foreign-trained physicians than US medical school graduates, leaving large numbers of otherwise capable FMGs unable to practice. In 2019 alone, more than 2,800 FMGs passed their required exams but were not matched with a residency program.

Most states also require longer residencies for foreign medical graduates than for US medical school graduates and in many cases, these requirements are up to three times longer for FMGs. Holding foreign and US medical graduates to the same standards is a fairly modest reform that would present little risk in terms of quality. A 2014 paper pushed in Public Choice concluded that “over a third of all US states could reduce their physician shortages by at least 10 percent within 5 years just by equalizing migrant and native licensure requirements.”

Many of the state-level pandemic responses point to opportunities for permanent reform. Early on in the COVID-19 crisis, several governors issued emergency orders that temporarily loosened restrictions on foreign medical graduates. New Jersey even granted temporary licenses to physicians already licensed in foreign countries. Unfortunately, the state is no longer accepting applications for these temporary licenses.

Conclusion

The aging US population is expected to result in a growing shortage of physicians over the coming years. Inflexible immigration policies and onerous licensing requirements are exacerbating the problem by preventing foreign-trained physicians from practicing medicine in the United States.

The COVID-19 emergency responses at the state and federal levels have specifically recognized the importance of foreign-trained physicians. However, it would be a mistake to dismiss concerns about physician shortages after the COVID-19 crisis subsides. Lawmakers should build on the lessons learned during the pandemic and pursue permanent reforms to expand the physician workforce.