As public policymakers grapple with an estimated $1.5 trillion in underfunded state and local government defined benefit (DB) pension liabilities, interest groups have been attempting to reverse recent reforms that have helped reduce future unfunded liability growth.

A combination of better funding policy and reductions in future benefits (e.g., lower accrual rates, reduced cost-of-living adjustments) have assisted in paying down some of these massive costs. Still, hardly a month goes by without releasing some article or study claiming to show the opposite—that these public pension reforms have made things worse. The arguments imply that any attempt to close a DB pension plan creates higher pension liabilities, increases costs, worsens employee recruitment and retention, and that any replacement defined contribution (DC) plan reduces employees’ retirement security.

Examination of these arguments, however, reveals that most of the claimed negative impacts of public pension reform are not supported by the facts. Here are some of the more common claims of problems caused by public pension reform and why public sector policymakers should not be swayed by them.

Claim: Closing a DB pension plan will increase plan liabilities

False: Closing a DB pension plan by itself does not impact existing plan liabilities. The accrued benefit promises made to the participants are the same before and after closing a pension plan to new entrants. Every dollar of benefits to be paid to these existing participants will be the same regardless of whether the plan remains open or is closed to new participants.

Claim: Closing a DB pension plan will immediately increase plan unfunded liabilities and increase required employer contributions

False: The claim asserts closing a pension plan causes higher levels of negative cash flow, which requires lower return investments for the plan to maintain the sound funding of the benefit promises that have been made. The argument (sometimes called “transition cost”) generally goes as follows:

- Closing the plan causes an increase in future “negative cash flow”–benefit payments that will exceed employer and employee contributions and investment returns coming in. This occurs because contributions for new hires are no longer being made.

- Increased negative cash flow means plan investments must be more liquid to pay benefits as the membership gradually diminishes in a closed plan.

- More conservative liquid investments mean lower investment returns.

- The expectation of lower investment returns means the assumed future investment return assumption must be reduced. (e.g., from 7% to 4-5%).

- Lower investment return assumptions for the future mean a lower discount rate is used by the plan actuary, causing an increase in unfunded liabilities.

- Higher unfunded liabilities mean employer contributions must immediately increase to make up for the lost investment returns.

The argument, while logically coherent, is very misleading because it suggests that a DB plan will always need new entrants to remain sound and affordable. If that were true, then it would mean a DB pension plan ought to never be closed because contributions will always be needed from future generations of taxpayers and employees to pay the benefits of current employees. This is not consistent with sound actuarial funding methods for pensions. DB pension plans are supposed to prefund benefit promises during the working years of each employee. If money is always needed from new hires, it becomes more like a giant Ponzi scheme that requires unending funding from, and risk-shifting to, future generations of employees and taxpayers. This would make public pension funding more like the nearly bankrupt federal Social Security system.

The “transition cost” argument is further weakened by the fact that there has never been a case where a plan sponsor with a closed public sector DB pension plan immediately changed their actuarial funding methods and assumptions because of cash flow concerns. It simply hasn’t happened because plan sponsors have decades to manage the closed plan liabilities and assets. Current participants in a frozen DB plan can expect to work 20-40 years before retiring and will have an additional 20-35 years in retirement. Examples of states that have closed their DB plan and moved to DC plans but have not immediately changed their investment structure and actuarial return assumption for this reason include Alaska, Michigan, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Utah, and most recently North Dakota.

Further, any increase in negative cash flow for the closed plan is a problem that gets smaller with time. The problem gets smaller as the size of the remaining liability decreases and as the number of retirees and benefit payments in the closed plan becomes smaller. Any funding volatility because of “negative cash flow” can be handled more easily in the future because it represents a much smaller piece of the financial picture of the plan sponsor. There is a lot of time to allow closed plan liabilities and investments to evolve without the need to push the panic button.

Those who criticize the closing of DB pension plans don’t often address the possibility that unfunded liabilities will increase if the plan is not closed. In an open pension plan, prolonged market outcomes below expectations and failure to make sufficient contributions will apply new costs to the benefit promises for new hires. No one seems to mention that risk when criticizing proposals to close an existing DB pension plan. Pension liability derisking efforts are severely handicapped if the plan sponsor cannot at least start curtailing unexpected costs for new hires.

Claim: Closing a DB plan will increase the actuarial required contribution percent rates for unfunded liabilities because the cost is being amortized over a frozen and diminishing salary base

True, but misleading: This is a non-problem because any unfunded liability can still be amortized by simply continuing to have employers fund the closed DB plan on the total compensation of both the DB plan participants and the new employees in the replacement plan. This helps ensure unfunded liabilities continue to be paid off as if the DB plan had not been closed. It also reduces negative cash flow impacts. Nothing has changed except new hires are not being asked to subsidize the unfunded liabilities of the DB plan participants with their own money. As long as unfunded liabilities are, on an actual dollar basis, being paid off at the current rate or faster, the required percent of payroll is inconsequential.

Claim: States that closed their DB plans have experienced higher employer contribution requirements because of greater exposure to volatile markets

Unproven: Critics sometimes assert that specific states have experienced unexpected cost increases for their closed DB plans because they have higher negative cash flow and greater exposure to market volatility. Closing the plan means the loss of contributions for new hires that could have been invested to weather volatile investment markets. Instead, the closed plan must cash out of investments to pay benefits and miss out on gains during periods of market recovery. This is claimed as an additional consequence of the negative cash flow argument previously discussed.

The proponents of this claim fail to specify what part of any employer cost increase is attributable to just the negative cash flow versus how much is attributable to other factors, including investment loss vs. assumptions, less than full actuarial funding by the employer, demographic experience gains and losses, or change in actuarial funding assumptions (e.g., discount rate). Only through a full attribution by source analysis can one know what marginal amount of cost increase is attributable to excess negative cash flow.

Claim: Moving from DB to DC negatively impacts employee attraction to public employment

Unproven and misleading: It has become axiomatic among DB pension advocates to claim that DB plans improve the attraction of employees compared to DC plans. Very little actual evidence has been presented in support of this claim. Usually, the argument is made that surveys show most employees like the idea of guaranteed lifetime retirement income and, because DB plans provide that, most employees will prefer employers that have one.

In contrast, the argument goes, DC plans do not typically offer guaranteed income features and have uncertain outcomes because investment risk is shifted to the participants. The assertion is that employees are less likely to want to join an employer that offers only a DC retirement plan.

This objection can be refuted by making a few points:

- Preferences for guaranteed income for life in retirement do not automatically require a DB pension. The preference can easily be satisfied by designing a DC plan to include guaranteed lifetime income features. There is no inherent reason why non-DB plans cannot accomplish this. See the Reason Personal Retirement Optimization (PRO) plan design for a good example of how DC plans can be structured to provide lifetime income, just like DB plans.

- DB pension plans actually do less to deliver retirement income security than many prospective employees might think. Most public employees are not full-career employees and never earn full DB benefits. One study by the Urban Institute and Bellwether Education Partners notes that because of the backloading of benefits and a lack of portability of benefits, DB plans have a particularly negative impact on employees with short and even moderate periods of service. The study examined the benefit accrual experience of teachers under DB plans and concluded that three in 10 new teachers leave within five years, thereby forfeiting their benefits. The study notes that because many teachers cross state lines to teach elsewhere they “split” their careers between multiple state pension systems, greatly reducing their retirement benefits compared to those who stay for a full career in one state. The study also finds that only 25% of teachers break even and earn a pension benefit that is equal to the value of the contributions made by themselves and their employers. If educated and informed properly, most employees who are focused on the value of their retirement plan should actually prefer a well-designed DC plan to a traditional DB pension.

Claim: Moving from DB to DC negatively impacts employee retention rates

Unwarranted conclusion based on misleading correlation of data: Some DB advocates claim that employee retention is hurt by the introduction of DC plans for new hires after closing a previous DB pension. They point to comparisons of retention rates of new hires into DC plans versus what the assumed retention rate would have been under the DB plan.

The comparisons show some level of worsening retention rates and conclude that the change must be caused by the adoption of the DC plan. A complete analysis, however, would ask more questions about other variables that might be contributing to the change in retention outcomes, including: Are the DB and DC groups comparable? Do they have similar demographic characteristics? Are the age and service, job occupations, and even geographic location characteristics the same? What other changes in salary and benefits might be affecting turnover? Generally, these other factors and variables are ignored by those making a shallow comparison between DB and DC employee groups. They often overlook changes in other societal factors and events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and changes in generational work patterns and preferences.

The conclusion that a DC plan worsens retention can, at best, be considered a weak correlation based on incomplete data and, at worst, is a purposeful attempt to mislead public policymakers.

A 2022 study by John Brooks of Appalachian State University examined the retirement and retention impact of public sector DC plans replacing DB plans, finding that a change in plan type has no significant effect on retirement decisions. The results suggest that public policymakers should focus more on employee contribution levels and other factors, not plan type, when intending to address recruitment and retention. A separate Pension Integrity Project analysis also found that changes in retention rates in some states are more attributable to compensation and changes in the broader labor market and cannot be attributed to changes in DB plans.

Claim: DC plans reduce employee retirement security compared to DB plans

False for most individuals: As noted previously, DB pension plans do a poor job of contributing to the retirement security of most employees. Traditional DB plans are designed to provide maximum benefits only for those fortunate few who work full careers in covered employment. The lack of benefit portability and backloading of benefit accruals does substantial damage to public employees who do not stay for a career. Short-service employees are subject to benefit forfeitures because of often lengthy vesting schedules that are common in public pension plans. Making things worse, employees who vest but leave covered employment with a deferred pension to be paid at retirement age will see the value of that frozen benefit massively degrade because of inflation.

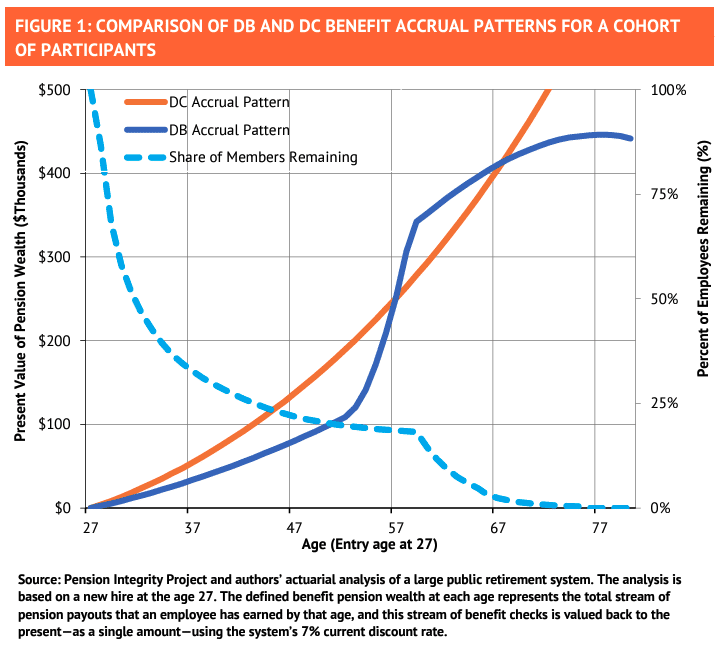

Figure 1 shows that traditional DB pensions are a poor fit for all but a narrow band of workers nearing retirement age. In most cases, the DC benefit accruals exceed DB pension benefit accruals until an employee reaches over two decades of service.

DC plans are also criticized because participants leaving employment can withdraw/cash out their accounts and not save the money for retirement. While this can and does happen, it is also true that DB plan participants who leave employment can withdraw their employee contributions, and many do. This usually results in the forfeiture of the entire accrued pension–even that funded by employer contributions. The retirement asset leakage problem is shared by both DC and DB plans.

DC plans can be designed to mitigate this concern by encouraging employees to keep their DC plan accounts intact after separation from service or by rolling those over to a tax-deferred account. Communicating the DC benefit as continuing to be invested with earnings growth over time that supports income in retirement can be a strong argument against DC account cash-outs. In contrast, DB benefits for employees who leave service before retirement are frozen and subject to loss of value because of inflation. Younger employees with frozen DB benefits are more likely to cash out because they see less value in keeping that benefit when they still have 20-30 years of work before retiring.

Conclusion

Studies condemning the adoption of alternatives to the traditional pension plan for public workers are not supported by the facts. DB pensions are not the only way to provide attractive and affordable retirement benefits to teachers, police, firefighters, and other public workers. Policymakers should not be misled by claims that there are unavoidable structural obstacles to reforming pensions or that changes will inevitably lead to problems with recruiting and retaining quality employees.