For individuals, businesses, churches, clubs, and other organizations and events to sensibly manage the risks of COVID-19, especially while reopening and resuming activities, they need information. Not just any information but reliable information that they can trust and that will help them make better decisions.

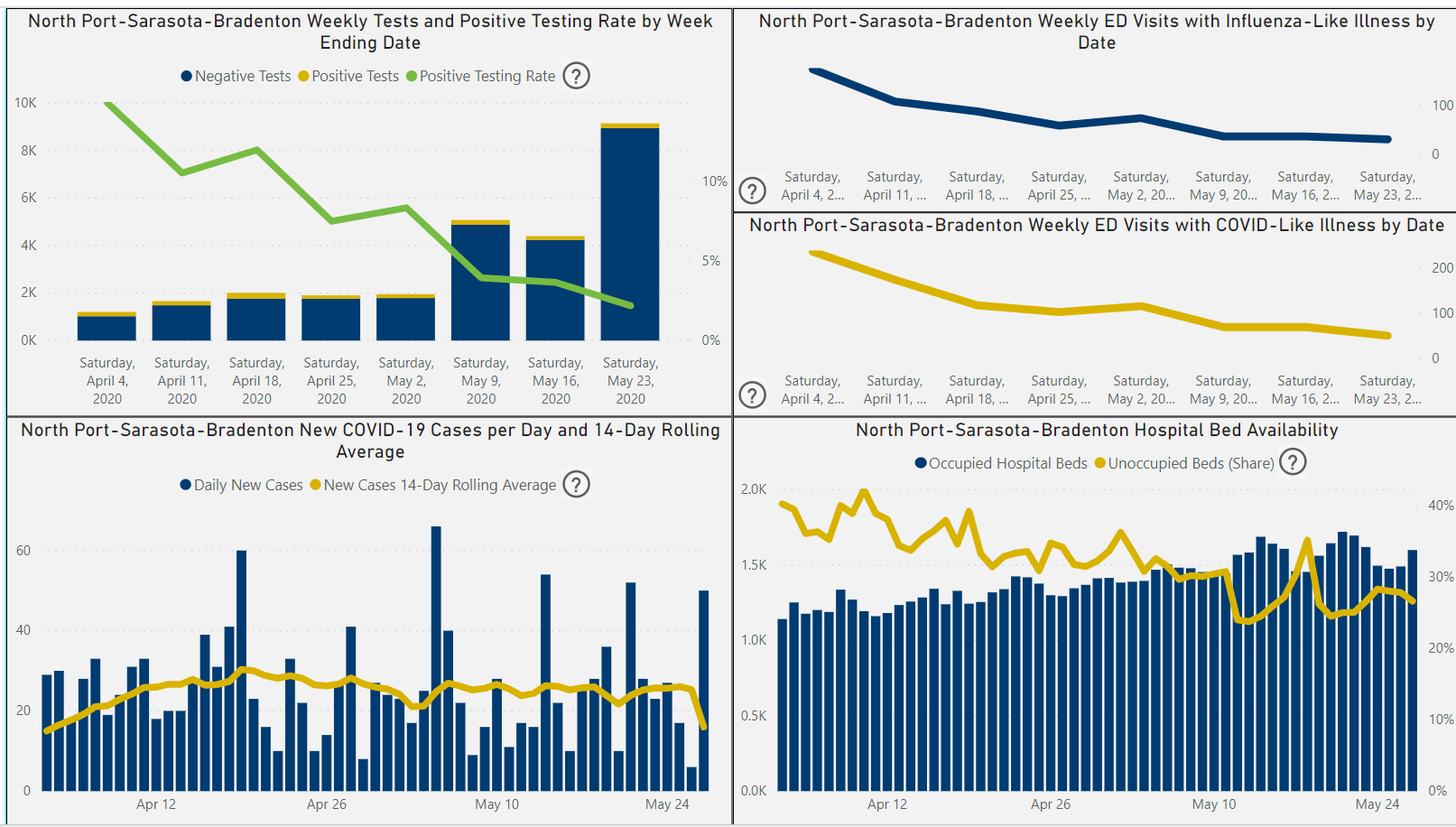

The Florida Department of Health provides a COVID-19 dashboard with data organized statewide, by county and by ZIP code that focuses on testing, cases and deaths. The Tampa Bay Partnership provides a dashboard that focuses on testing, cases and hospital utilization. The graphs below are taken from that site for the Sarasota area on May 28.

Although this information is useful, on its own it doesn’t help people make good decisions about how to manage the risks associated with COVID-19. Some people, especially those at high risk of severe health consequences from the coronavirus, want information that helps them avoid exposure. Others might only want to know if they’ve been exposed, if they are infected or if community cases are spiking, calling for renewed precautions.

The first information people need, which is not readily available, is about the relative risks of various activities and situations. The one-size-fits-all “just stay home“ approach of the lockdowns does not make sense, nor works well, except possibly as a very short-term emergency measure. It is good that Florida is removing the lockdowns. But now people need risk-based information to safely resume normal activities.

For example, we know there’s vastly less risk of transmission out of doors than inside. We know there’s less risk with less crowded and better ventilated indoor settings. We know there’s less risk if people are wearing masks that prevent them from coughing or sneezing or otherwise releasing infected droplets into the air. We know that it’s possible to get the virus from touching a surface and then touching your face — but that most transmission is through the air. We know that older people and those with certain preexisting conditions are much more likely to die or have serious illness if they contract the coronavirus.

Ideally, people who are or might have been infected with the coronavirus should self-isolate, get tested, and, if they have even mild symptoms, seek treatment. But they still need access to pharmacies, doctors, groceries, etc., and it’s probably good for them to get exercise and sun. So they need to know the risks associated with these activities and how to avoid exposing others. But COVID-19 is more likely spread by people who don’t know they’re infected and who therefore don’t take precautions to protect others. In other words, we lack testing.

Unfortunately, governments seem very hesitant to give useful information to people. Indeed, governments often seem reluctant to let patients have their own information. A few years ago, the Food and Drug Administration stopped 23andMe from providing some health information pertaining to a person’s genetic code directly to that person on the grounds that some people would not know how to interpret the information. More recently, the FDA shut down a COVID-19 testing program backed by Microsoft founder Bill Gates because it allows home testing and provides information directly to patients. Such paternalistic efforts to prevent people from having information that authorities are afraid they will misinterpret are always problematic, but during this pandemic they can be especially harmful.

Other information would be useful as well. For example, knowing the actual incidence of the virus in a location or neighborhood would help us know the likelihood of encountering someone who is infected. This information can best be obtained by testing a more-or-less random sample of the population. But testing is now mainly being done on people who have symptoms or have been exposed to the virus or have workplace reasons to be tested. The latter is important too, but it is clearly skewed toward people more likely to be infected and to test positive, so it doesn’t give a good picture of how many people have the disease, or where, and makes it more difficult to take precautions.

Testing a greater fraction of the community and publicizing that information can also be used to help everyone resume activities while continuing to take appropriate action to manage risks. Precautions like social distancing and better sanitation help a lot, but they can be improved with good information.

One source of information is contact tracing, which helps identify people who have had contact with an infected person and therefore might have been infected themselves. This can now be done quite effectively with contact-tracing smartphone apps. These work by sharing anonymized information, voluntarily entered into the app, with others who also have the app running. Users of the app are then notified if a person with whom they have had contact subsequently becomes infected. (Full disclosure: One of the authors is involved in a consortium developing such an app.)

Already, a number of businesses, events organizers, churches and other organizations are looking at how having employees, participants or members use one of these apps might help everybody better manage their risks of being infected. If you get a warning from your app that you might have been exposed, you can go get tested and meanwhile inform your employer, who might want to keep you away from other employees and customers for a few days until the test results are in. And maybe you won’t go to church or a club event or something else until you know your test results.

Although information about the prevalence of COVID-19 in an area, combined with status and contact tracing apps, can help individuals and private organizations better manage risks, there are ways state and local governments can use testing data and information as well. If positive tests indicate a certain area — as broad as a part of town or a certain beach or as narrow as a certain resort or business — is having a surge in the incidence of the coronavirus, they can work with people there to try to figure out what’s going on and inform everyone who might have been exposed, so they can voluntarily isolate and get tested. At the same time, they might be able to see that certain areas or activities, such as a beach, park or facility, are not experiencing unusual numbers of positive tests and therefore worry less about potential transmission there. It’s all about using the data to help focus energy and resources.

For these ideas to work most effectively requires extensive testing, widespread availability of testing and effective communication of anonymized test results. Although the amount of testing has been ramping up nationally, within Florida, and even locally, there is still a ways to go before these risk management tools can be widely utilized. This should be a priority for governments at all levels.

A version of the column originally appeared in the Sarasota Observer.