The U.S Department of Justice recently announced plans to phase out its use of private prison contracting. And for nearly a year now, presidential candidate Hillary Clinton been going even further, expressing support for a wholesale ban on the use of private prisons by state governments. A private prison ban would be bad for California.

The state has used private prisons in targeted ways dating back to late 2006, when California began to house inmates in privately operated out-of-state prisons as part of a multifaceted strategy to reduce severe overcrowding in state-run prisons. At the time, California had just seen its prison health care system placed under federal receivership due to a court ruling that the medical care California was providing to prison inmates was inadequate and an unconstitutional form of cruel and unusual punishment. Years later, this was followed by a ruling from three federal judges demanding the state dramatically reduce its prison population to address overcrowding that the court found threatened the health and safety of inmates.

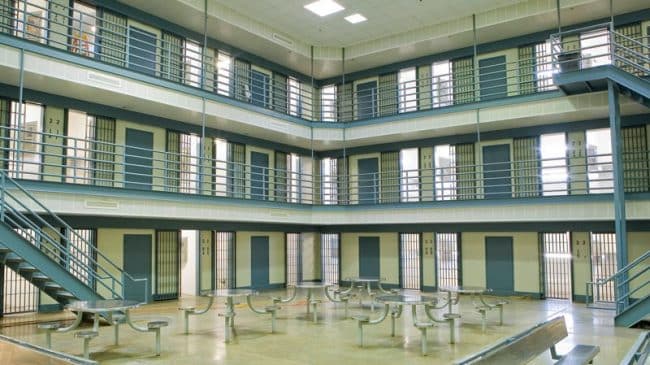

Private prisons have provided California with an important relief valve for a decade, serving as part of a larger package of efforts designed to end prison overcrowding and reduce the high cost of corrections. Without private prisons, California would have been forced to spend billions building new prisons or renovating existing prisons to comply with court orders. The debacle of the state-run prison system, which featured massive prison overcrowding and operated a failing health care system that performed so badly the federal government took it over to end ongoing civil rights violations, needed help from the private sector.

California started sending several hundred inmates to out-of-state private prisons in late 2006. But by the end of 2010, the state had sent over 10,000 inmates to be housed in such facilities.

Notably, Gov. Jerry Brown once expressed his intention to phase out California’s use of private prisons upon taking office. However, dealing with the realities of California’s prison woes has prompted Brown to continue to rely on private prisons. As of last month the state still had nearly 4,800 inmates housed in out-of-state private prisons.

Banning states from using private prisons would take vital options off the table. How would California have dealt with its overcrowding crisis without shifting thousands of inmates to private prisons over the past decade, for example? Failing state prison systems like California’s — or even states simply needing to address aging prison facilities in need of replacement — wouldn’t have options to turn to in times of need if a ban were imposed.

Private prisons should be viewed as a tool that lawmakers can use to improve the criminal justice system. We’re seeing countries like the United Kingdom, and states like Pennsylvania, experiment with corrections contracts that connect private prisons’ compensation to making demonstrable progress in reducing recidivism rates of their inmates after they’ve completed their prison sentences. Not only do such these agreements prompt the private prison providers to improve their inmate rehabilitation and education services to drive better outcomes when people re-enter society, but they also shift the overall focus of private prisons from simply filling prison beds to actually helping offenders so they don’t re-offend and cycle back through the prison system again later.

Given this emerging paradigm in contracting in private prisons, and the state government’s epic failures in prison management, banning private prisons would be foolish. California’s decade of sensible use of private prisons to help address severe prison overcrowding shows how private prisons can assist states in times of need. Instead of scapegoating and targeting private prisons, state and federal officials should embrace them as tools to help improve offender rehabilitation programs, reduce recidivism rates, and deliver on needed criminal justice reforms.

Leonard Gilroy is director of government reform at the Reason Foundation.