In a recent commentary at Forbes.com, Edward Siedle alleges what he perceives to be inadequate savings, makes a plea to Alaska policymakers to rid themselves of their defined contribution retirement system and return to a defined benefit pension design that was frozen to new public employees in 2006. While Siedle’s critique about how some defined contribution retirement funds operate is not without merit, most of the article does not hold up to scrutiny.

In the piece, Siedle mentions that “flawed 401(k) defined contribution plans” could not produce adequate retirement results. This is based on a poor understanding of what a defined contribution (DC) plan can accomplish, and it is not the case in Alaska. In the corporate world, 401(k) plans were originally intended to be tax-deferred savings plans designed only to supplement existing defined benefit pensions. But when the private sector largely moved away from defined benefit pension plans because of funding risks and a changing workforce, they often replaced them with broader 401(k)-style defined contribution plans that were intended to replace the level of benefits being offered previously.

Unfortunately, the retirement income focus of the defined benefit pension designs was typically not carried forward in these new 401(k) plans, with wealth accumulation being the default focus. Siedle rightly identifies this as a fault. The typical 401(k) plan does not have the income-focused design necessary to be a true retirement plan. Make no mistake—this is not a fundamental shortcoming of all DC funds. Rather it is an absence of articulated plan objectives that led to plan designs with suboptimal outcomes. The mistake he makes is in stopping there as if no other inquiry should be made. Many DC retirement plans have, and do, focus on income and are excellent designs.

If a proper inquiry is to be made, it should be understood that the ultimate benefit to a participant from a retirement plan is not determined just by whether the plan is DC-based or defined-benefit-based. That over-simplification ignores a large list of other factors, including benefit accrual structures, vesting rules, the level of funding from the employer and employee, the employee’s tenure, age at entry into the plan, investment performance, and work and compensation patterns as major examples.

The commentary uses an analysis from the Alaska Division of Retirement and Benefits (DRB) to conclude that the state’s DC plan is providing “significantly smaller benefits than the pension-style system discontinued in 2006.” Again, Siedle takes this as evidence to make a categorical judgment about the evils of DC plans. But he fails to ask a simple question: To whom is this DRB analysis relevant?

The Alaska Division of Retirement and Benefits comparison was addressing only a narrow cohort of longer-term employees, and it did not purport to say that all employees in all circumstances would be better off under the old pension plan than the new DC plan. If one looks at a broader set of employees with different lengths of service, the result is quite different.

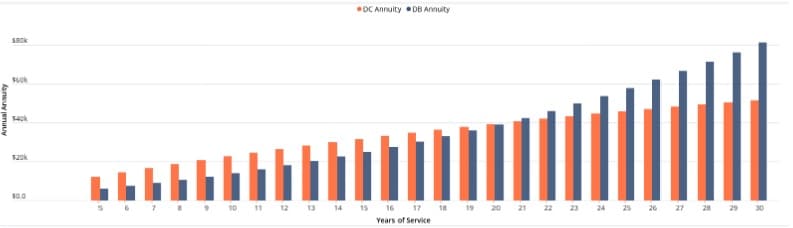

Pension Integrity Project analysis (Figure 1) compares the defined benefit (DB) pension proposed in a bill being considered in the Alaska legislature and the state’s current defined contribution plan. The analysis projects annuity values for regular public employees (teachers and public safety modeling show slightly different results) with an entry age of 30. The results clearly show that for any employee the DC plan will provide higher lifetime income benefits for the first 20 years of service. It is only the small number of very long-service employees who may be earning a higher benefit amount. For the vast majority of Alaska’s employees, the DC plan can be a more effective way to provide retirement benefits than the DB plan.

Figure 1: Comparing the Value of Alaska’s Defined Contribution Plan to the Proposed Defined Benefit Plan at Different Years of Service

Source: Pension Integrity Project actuarial modeling of Alaska’s existing defined contribution plan benefits compared to the pension benefits being considered in the proposed Senate Bill 88. This analysis displays results for non-teacher, non-public safety employees. The analysis assumes entry age 30, 6% DC investment return, 5% annuity payout rate, and 2.75% annual salary growth, and that DC benefits are not annuitized until normal retirement age.

The reality is that defined contribution plans can and are often used as the foundation for well-designed and effective retirement plans. Just look to Alaska’s higher education system for a local example. In fact, the primarily DC-based national higher education retirement system (for both public and private institutions) is arguably the most successful retirement system the country has ever produced because of adequate contribution rates, portability of benefits, and the flexibility to take retirement benefits as lifetime income, a position validated by a recent survey of higher education institutions.

This key point missing from the article is that it is very rare for employees in any industry to spend a full career with any single employer today. This anachronistic notion is a primary reason defined benefit plans have dwindled, although it remains the basis for defining success in remaining public sector DB plans today. The problem (aside from potential ongoing crippling unfunded liabilities) with most DB plans is that the employee must spend a full career with the same employer to receive a lifestyle-sustaining income in retirement. Public defined benefit plans, like the old Alaska plans, are designed to heap up benefits in later years and are not portable. It is only in the later years nearing retirement that an employee’s benefits would accrue significantly. Those benefits and accrued assets do not travel with the employees as they change employers throughout their careers, they sit in the pension fund until the employee reaches the retirement age set by the plan.

Alaska’s defined contribution plan, however, is designed to be portable and move with employees as their careers span several employers and there is no backloading of benefits. The issue of benefit portability is critical when determining effective retirement plan designs today. In Jan. 2022, median state employee tenure nationally was measured at only 6.3 years. It is clear that most employees in the modern workforce will have a fair number of employers during a 30–40-year career. Another example of this comes from the Pension Integrity Project analysis of the Colorado PERA School Division, which shows that only 37% of hires remain in the system after five years of service. Benefits that are illustrated based on formulas may look adequate on paper, but if only about a third of workers will actually get that level of benefit the illustrations are essentially meaningless.

Siedle also makes the misleading argument that in defined contribution plans Wall Street bankers make money at the expense of retirement plan participants. We retort: Are Wall Street investment firms not involved in managing the hundreds of billions of dollars in state and local governments’ defined benefit pension plans? Of course, they are. Large pools of pension money enjoy the benefit of favorable rate classes of investments. This is true for DB plans and should be for DC plans as well.

While the portable nature of DC plan benefits fits the modern workforce better than traditional DB plans, typical 401(k)-style DC plans do have their own shortcomings. As previously acknowledged, a DC plan design that is focused on wealth accumulation rather than income replacement may be overlooking its primary purpose. The Pension Integrity Project recently introduced a new plan design called the Personal Retirement Optimization Plan (or PRO Plan) that uses existing market-available products and is built on a DC foundation but is focused on income replacement. The PRO Plan further focuses on DB-type lifetime income benefits at the individual participant level—producing previously unavailable customized benefits.

Whether or not a retirement plan is DB or DC logically has no direct impact on plan effectiveness. While the defined contribution plan in place in Alaska could be enhanced, it is a plan that recognizes the reality of the modern workforce and works to meet employee needs. A theoretical and flawed comparison of defined benefit and defined contribution plans does not shed light on the reality facing public employees and employers in Alaska today. Responsible retirement plan experts should honestly focus on how retirement plan objectives and design, not defined benefits vs. defined contributions, can combine to meet the needs of both employers and employees in the modern environment.