Many air travelers found their flight plans disrupted in mid-July when system disruptions from a faulty cybersecurity software update led to widespread computer crashes. Major airlines like American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, and United Airlines requested the Federal Aviation Administration issue ground stops for the airlines, all of which were paralyzed by computer outages.

This incident highlighted the need for robust information technology (IT) preparedness and operational resilience for airlines, as well as the vulnerability of automated update systems or updates managed by third parties.

What happened?

The problem began on July 19 when users of CrowdStrike’s Falcon sensor began experiencing a blue screen (colloquially called a blue screen of death, or BSOD) loop. The Falcon Sensor is software that analyzes connections on the internet to determine if a connection is malicious. A BSOD loop like this occurs when the system is booting up but encounters an error when verifying system files, causing the computer to crash instead. This specific BSOD loop was caused by an update to the Falcon Sensor, which altered Windows system files. The changes caused errors in the boot process when a Windows system was starting.

Computers receiving the update installed it automatically. This occurred because CrowdStrike operates, as many competitor IT firms do, at the enterprise level. Contracts explicitly state that warranties are only valid if a client/enterprise is using the most up-to-date version of the software. Users could not have prevented the update. CrowdStrike runs Falcon as a service and software package—not just software. CrowdStrike’s clients are limited in what they can do with Falcon once it is installed by the terms of service.

CrowdStrike also stressed that this outage was unrelated to a cyberattack, and its customers’ data was still secure. Additionally, the affected file was only present on Windows systems. Computers running on Linux or MacOS were unaffected.

How was it fixed?

CrowdStrike responded quickly and released a patch in a little over an hour, but computers stuck in the blue screen of death loop could not receive it. A computer in a blue screen loop is unable to boot and, therefore, unable to download and update software. Essentially, nearly every affected computer had to be physically accessed by IT staff to resume regular operations. Networked computers could be fixed in larger groups at once through a set of standards known as a “preboot execution environment.”

What was the impact on the aviation industry?

During the outage, the FAA ordered a global stop on all flights for the three legacy airlines. Flights that were in the air would reach their intended destination and then stop flying until the order was lifted. During the outage, no American, United, or Delta flights were allowed to take off. Like other sectors, the fix for the Falcon update had to be manually implemented by the airlines’ IT staff. Depending on the network status of the computers affected, the fix had to either be done by hand on every computer in a system or network-wide through a preboot execution environment.

Although the precise costs have not yet been determined, the extensive labor and productivity losses for airlines using the affected CrowdStrike systems suggest that expenses will be significant. Microsoft estimates that 8.5 million Windows devices, or less than 1% of global Windows devices, were affected by the CrowdStrike outage globally. That number is across all sectors, not just aviation.

Delta Air Lines, which canceled over 5,000 flights, has said it plans to sue CrowdStrike, alleging up to $500 million in damages from the outage. Investopedia reported, “CrowdStrike attorney Michael Carlinsky said Delta largely ignored its offers for assistance and contributed to a ‘misleading narrative’ that CrowdStrike is responsible for the way the airline responded to the outage.”

How well did airlines recover from the outage?

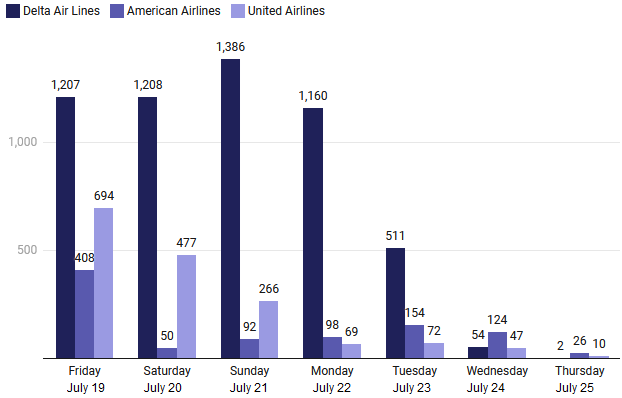

Recovery times from the CrowdStrike outage varied heavily from airline to airline.

Figure 1: Canceled Flights by Legacy Carrier by Day

Source: Matt Ashare, “American Airlines credits IT teams with quick recovery from CrowdStrike disruption,” CIO Dive, 2024.

American Airlines, on July 19, grounded and canceled more than 400 flights in the first 24 hours. The following day, however, American only had to cancel 50 flights, per flight tracker FlightAware, as shown in Figure 1. American Airlines has praised the quick response of its IT teams but has also accredited much of its success to robust crew-tracking software. Knowing exactly where every working member of American Airlines was at any given time served as a buffer and allowed for a return to operational normalcy faster, according to American Airlines CEO Robert Isom.

United Airlines returned to a semblance of operational normalcy on Monday, July 22. United required the manual recovery of “more than 26,000 computers and devices one at a time” at United centers spread across 365 airports globally. This major disruption came a day after United Airlines leadership “lauded United’s operations and technology teams for their work to reduce the recovery time and cost of previous operational disruptions.”

But, of the three major legacy carriers, Delta Air Lines’ recovery from the CrowdStrike outage was by far the worst. Delta’s crew-tracking software was overwhelmed by the outage and took the most time to recover and manually resynchronize, according to Delta. On Tuesday, when both United and American had largely returned to normal operations, Delta still had to cancel 511 flights, bringing its total canceled flights to over 5,000. Delta recovered to pre-disruption levels on Thursday, July 25, nearly a week after the July 19 outage.

Delta’s relatively glacial recovery time prompted the U.S. Department of Transportation to open an investigation into Delta over its “uniquely severe flight disruptions.” The investigation will likely uncover the root causes, but those answers are likely an abundance of critical computer systems running the Falcon sensor package, a lack of IT preparedness for an outage, or some mixture of both.

What can be done in the future?

CrowdStrike has released a full analysis detailing what went wrong and what can be done to mitigate an outage like this in the future. CrowdStrike plans to have staged deployments for updates in the future by region, time zone, etc. This means that when a time zone or region reports problems, the rollout can be stopped before it impacts systems worldwide. Additionally, CrowdStrike stated it plans to provide customer control over the deployment of updates. Beyond these changes, more rigorous testing seems necessary to prevent an outage of this scale in the future.

But the airlines are not blameless either. While prevention was near-impossible, recovery and outage resilience were largely in the hands of the airlines—especially after CrowdStrike released a patch fixing the issue. Crew-tracking systems for American handled the outage well and kept the airline relatively functional in the days following. Delta’s software was overwhelmed, which led to the airline’s slow recovery in the aftermath. United, having just invested in operational resilience, saw its investment justified.

Given the impact of CrowdStrike’s outage, airlines should focus on IT system resilience efforts. Having crew-tracking software that functions on the best of days is fine, but it ideally should still keep crews in communication during outages as well. A week after the outage, Delta CEO Ed Bastian reported that the airline had lost $500 million, which may be an underestimate.

Having thousands of angry customers and substantial financial losses should motivate airline management teams and shareholders to pursue additional investments needed to address IT infrastructure weaknesses and avoid suffering from surprise outages in the future.