Editor’s Note: Psilocybin is still illegal under federal law, and many people are wary of being publicly identified, so this report only identifies those who are psychedelic professionals or have already been vocal about their experience.

On a cool April evening, the author of this report hosted some friends for a Shabbat meal in Denver. Before everyone sat down to enjoy matzo ball soup and lamb chops, guests were given the option to sip on a small brew of cacao, lemon, and a little bit of crushed psilocybin, also known as ”magic” mushrooms.

The host had largely given up alcohol and found that psychedelics helped him better celebrate the weekly Jewish call to relax and connect.

Knowing that this was a largely alcohol-free event, one guest greeted the host with dried mushrooms presented inside a tall wine bag with a fancy felt exterior and thin rope handles. This friend had grown the mushrooms himself and offered them as a gift, just like it is customary to bring an extra bottle of wine to a dinner party.

The guests enjoyed some laughs, thanked the chef for catering a delicious meal, and gently parted ways. From the outside, no one would have suspected this was anything but a typical dinner party. And it was all legal thanks to Proposition 122, Colorado’s 2022 ballot measure that legalized the limited personal possession of psilocybin (and other plant-based psychedelics).

In May 2023, Reason Foundation released a preliminary report on the public health impacts of legalization. Since then, our team continued to collect data and interviews with hospitals and law enforcement agencies. Interviews and public datasets have not shown a noticeable spike in either crime or hospitalizations.

So what were the outcomes of the initiative? To investigate what was happening behind the data, this author spent extended time in Denver, Colorado, participating in a wide variety of psychedelic-themed events.

How Colorado got here

For the past two decades, private philanthropists and activists have been the driving force behind psychedelic legalization. In Colorado, New Approach’s psychedelics initiative was backed by millions from donors, including GoDaddy Founder Robert Parsons and David Bronner of Dr. Bronner’s soap company. To date, no state legislative body in the United States has passed a bill legalizing the possession of psychedelics. Government funding for scientific research remains a small fraction of what has been donated through private philanthropy to advance clinical trials.

The consensus among agencies and elected representatives is that voters should wait for more research and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval.

As voters prepared to decide Prop.122’s fate in 2022, 30 Colorado officials, including mayors and a former governor, signed a letter opposing Proposition 122. Major newspaper editorial boards, including The Denver Post, ran opposition pieces. The Colorado Springs Gazette painted a picture of streets running rampant with drug abuse, exacerbating an already out-of-control downtown problem.

“That’s what we don’t need in a state struggling with rising and disproportionate rates of suicide, overdoses, homelessness and routine exhibitions of ill people on street corners openly hallucinating and talking to the sky,” wrote their editorial board in advance of the election.

Colorado voters nonetheless approved the ballot by a slim 53% margin in November 2022, making Colorado the first state in America where residents can legally grow and share psilocybin mushrooms.

Above ground, unlicensed healers

Nestled on a suburban street in Denver, the Plant Magic Café occupies a gable-roof single-family home with a not-so-subtle gigantic inflatable mushroom that could rival a car dealership’s flapping Labor Day sale balloon.

During a recent “dosas and mimosas” social event, guests paying a $25 ticket were greeted with a bowl of complementary mint tins with a slide-open top filled with microdose psilocybin mushroom capsules.

Proposition 122 technically allows psychedelic therapy only under a new regulatory framework of state-certified facilitators. Two state agencies, the Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies (DORA) and the Colorado Department of Revenue, are going through the painstakingly slow process of bureaucratic meetings to construct a detailed set of rules for the training and administering of psychedelic services. Regulated therapy will be up and running sometime in 2025.

But, in practice, professionals can skirt this rule by selling “harm reduction” coaching while simultaneously “gifting” mushrooms—a loophole that later was explicitly protected with the passage of Senate Bill 290.

By law, these unregulated guides cannot advertise services, but they can do many ceremonial and therapeutic practices that a government-approved guide will be able to perform, all without fear of criminal penalties.

Meaghan Len’s Plant Magic Café rents out its building to guides, many of whom live a nomadic lifestyle and specialize in ceremonial services for a particular psychedelic. It’s a convenient place for newbies with no personal connections to get introduced to non-recreational psychedelics.

One endearing story of healing with the assistance of unlicensed guides in Colorado was the subject of CBS News coverage. CBS followed a group of three generations of women—a grandmother, a mother, and two daughters—who went to a Colorado clinic for psilocybin therapy. One of the daughters told the news channel that she had been hospitalized for acute anxiety and panic attacks and that traditional pharmaceutical treatments offered no relief for her condition.

After the trip to Colorado, the daughter reports that her score on a standard psychometric test for anxiety, the GAD-7, plummeted from a 19 of 21 to a three (from severe anxiety to below mild). “A few weeks after journeying, I can truly say that I’ve never seen this much in a shift of my anxiety and in my life so quickly,” she said.

Safety and gifting of whole mushrooms

Illicit drug markets may include dangerous products, and psychedelics are no different. They may contain contaminants or may be manufactured without basic safety precautions.

A recent report by an Oakland-based testing facility, Hyphea Labs, found that some clandestine chocolate mushroom manufacturers sneak in adulterated synthetic psychedelic compounds, such as 4ACODMT, which mimics the effects of psilocybin.

The FDA recently published a bulletin after numerous reports of severe illness from consumers who ate ”microdose” mushroom edibles. While this brand, Diamond Schruumz, could be sold somewhere in the city, in our reporting, we did not find any shops selling them; indeed, whole mushrooms were more common than the mushroom chocolate varieties widely sold in other states.

In June, the Denver “Shroom Fest” held a trade show for the city’s psychedelics market. The most common products at the show were cultivation kits, which included all the essentials, such as soil, seeds (spores), and a clean container for growing psychedelic mushrooms. Some vendors did display edibles, but most products were for whole mushrooms. There were also services to test the prevalence and potency of psilocybin products.

Cultivation has made botanical, easily identifiable psychedelics widely available.

According to activist Aaron Orsini, mushrooms grow in plentiful surplus once properly seeded. There is little difference in effort between growing a small personal supply and a larger amount for friends. So, Orsini helped organize a gifting exchange group in the city simply because many cultivators had far more mushrooms than they knew what to do with.

If residents don’t want to wait a few weeks to grow their mushrooms, they attend a public event and learn how to join an open-invite exchange group that hosts frequent gatherings.

It’s too early to tell whether easy cultivation and sharing will lead to fewer poisonings, but is one potential reason why many news stories of accidental psilocybin chocolate consumption are happening outside of Colorado.

Microdose coaches and art day

In the attic of a private members club near downtown Denver, attendees convened for a recent ”microdosing and arts” ticketed gathering.

Near a tiny altar with incense at the center of about six people sitting cross-legged in rapt attention, two facilitators handed out small, color-coded pills of crushed psilocybin. Each color represents a different dosage. The red pills represented dosages too large for this event, so attendees were encouraged to pick a green or purple, each representing the equivalent psilocybin that would be present in less than half a gram of raw mushrooms—a barely perceptible fraction of a therapeutic dose (hence the term, “microdose”).

Under Proposition 122, professionals can hold “harm reduction” gatherings where they oversee psychedelic experiences.

One of the facilitators, Seth Marcus, is a professional coach who advises newbies on protocols for low-dose psilocybin. In every other state except Colorado and Oregon, the cottage industry of psychedelic therapists and coaches can only legally advise clients who have chosen to obtain mushrooms on their own from illicit sources. In Colorado, coaches and therapists don’t have to hope clients can secure safe products. They can serve them the whole way.

The entire event proceeded without incident. The attendees spent two hours calmly and quietly painting imagery reflecting their feelings.

Because personal possession is legal in Colorado, consumers can feel more comfortable choosing a lower dose. In contrast, in Oregon, where psilocybin must be administered under a state-certified supervisor, even very small doses administered in a more cost-effective group setting can cost more than $500 per session. This means consumers are incentivized to select larger doses because they don’t want to waste their money on an experience so small they get nothing out of it.

“My concern with relying too heavily on one dose is that it may cause the patient and the practitioner to feel pressured to push the dose too high, too fast. Doing this work piecemeal allows clients to be eased into the work and the medicine, without overwhelming their nervous systems,” says Dr. Erica Zelfand, CEO of Right To Heal, a psychedelic retreat in Mexico, and lead educator at InnerTrek, a school for certified Oregon psilocybin facilitators. (Disclosure: This author is a board member of Right To Heal.)

Data on crime and hospitalizations

Crimes associated with psychedelics are relatively rare, but when they do occur, they can get outsized media attention and skew the overall impact of a policy.

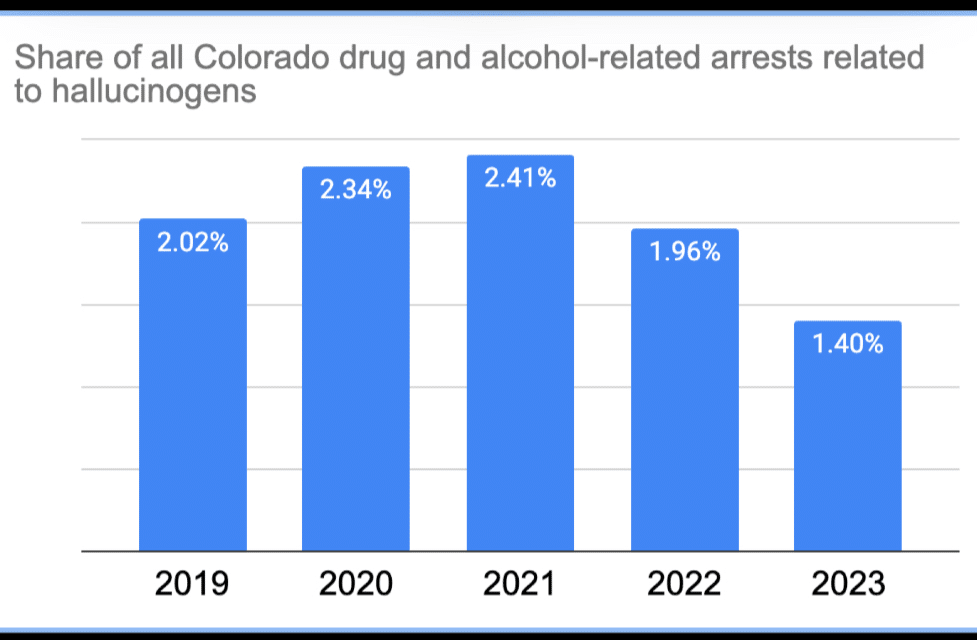

As can be seen from the graphs below, hallucinogen-related crimes and hospitalizations peaked in 2020 and 2021 but have fallen since, and there’s no noticeable spike in incidences following legalization in December 2022.

In 2023, there were 278 hallucinogen-related drug crimes, compared to 396 in 2022 and 408 in 2020. Since total drug arrests vary year by year, we also report hallucinogens as percentages of all drug-related crimes. In 2023, 1.4% of drug-related crimes involved hallucinogens, 1.96% in 2022, and 2.41% in 2020 (also the peak year in percentages).

Figure 1. Share of all Colorado drug and alcohol-related arrests related to hallucinogens (2019-2023)

Figure 2. Share of all Colorado drug and alcohol-related hospital admittances attributable to hallucinogens (2018 – 2023)

Reason Foundation reached out to law enforcement agencies and hospitals that have jurisdiction in the most populous 10 counties in Colorado. Five of the 10 law enforcement agencies confirmed that they had not noticed any uptick in crime (four others had no opinion, and one did not respond).

A spokesman for the Denver Police Department told us in 2023 (and subsequently reconfirmed this year) that “psilocybin has not been a significant law enforcement issue in Denver either prior to or following the passage of Proposition 122.”

Our research generally mirrors other studies. One large global survey of drug users found that 0.2% of psilocybin users have visited a hospital in the past year (another found 0.4%) due to adverse reactions to the substance.

So, police aren’t seeing a change in crime under statewide decriminalization, and hospitals aren’t overburdened with patients.

(Note: Methodological details about our data collection practices are available upon request to the author. A forthcoming data project will publish these details and make them public.)

Demand hasn’t changed much

In 2019, the author visited Amsterdam, the Netherlands, to see what a city was like with legal psilocybin. To his surprise, the native Dutch didn’t have much interest in psilocybin, which can be purchased in neatly packaged containers of whole truffles in retail stores throughout the city. A psychedelic retreat he attended was nearly all foreigners. Psilocybin is available, and some Dutch may choose to consume it on occasion, but it is not an overwhelming or even mainstream part of the culture

The initial experience in Colorado seems quite like the Netherlands.

Shannon Hughes, director of The Nowak Society, a psychedelic trade group, says there’s been a slight increase in inquiries from older patients. But otherwise, there’s been little change in demand since 2022.

“Honestly, other than more people speaking more freely about their work with mushrooms or their desire to access mushrooms for personal healing, I have not myself witnessed too many impacts,” Hughes writes to Reason. “A thriving ‘underground’ community has been in operation in Colorado for a long time and nothing there has changed.”

While there are no official state-wide statistics on psilocybin use yet available to the public, Reason Foundation’s observations and those relayed by professionals within the industry largely mirror what happened with cannabis nearly a decade ago.

Laws—especially drug laws—tend to follow behaviors that voters are already doing. After all, Cheech and Chong became household names for their comedy films celebrating America’s love affair with marijuana decades before Colorado began licensing dispensaries.

And marijuana studies back this up. After a state legalizes recreational cannabis, about 20% more consumers may pop a gummy at a party or try out a tincture for better sleep. However, even in studies that find an impact, the availability of legal cannabis doesn’t reliably increase chronic use more than a few percentage points.

The folks who wanted to use cannabis were already consumers. Mushrooms appear to be following a similar path.

Conclusion

As with recreational cannabis a decade ago, all eyes are on Colorado again as a testbed for other states considering the legalization of psychedelics.

Critics often argue that reforms are moving faster than research.

“Future data may show that psilocybin use is safe without medical oversight. But given current evidence, we advocate oversight by trained mental health professionals and slowing of sweeping legalization efforts while the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s evaluation and approval processes unfold”, wrote a team of researchers for a correspondence letter in the journal Nature.

Yet, millions of people have used mushrooms all over the world for centuries in legal and illegal markets.

Denver looks only mildly different in 2024 than it did in 2022–and quite like Amsterdam in 2019.

Psilocybin has risks, as does any other drug, including FDA-approved pharmaceuticals. Some people will look at public health statistics in legal jurisdictions and conclude that psilocybin should only be available through a doctor. Others will conclude that they’re perfectly safe for recreational use. But, as other states consider reforms similar to Colorado, voters and policymakers can be confident that the impact of legalization has become predictable.