In Nov. 2022, Colorado voters passed Proposition 122, allowing for the legal possession of some plant-based psychedelics and tasking the state to create a framework for “healing centers” where psychedelics can be administered under the supervision of certified professionals. This was the first ballot measure of its kind in the United States, and it has the potential to open up a new field of research and therapeutic applications.

Psychedelics have seen increasing interest in recent years due to their potential for therapeutic uses. The Food and Drug Administration has fast-tracked two psychedelic drugs, MDMA and psilocybin (the active ingredient in psychoactive mushrooms), for post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. Additionally, many of America’s top research institutes, from Johns Hopkins to New York University, have published studies showing that psychedelic drugs are potentially superior to current treatments for a range of mental illnesses, from alcohol use disorder to anxiety.

Opponents of the Colorado measure worry that it could lead to abuse, endangering public safety and taxing health resources. While extremely rare, there are isolated anecdotes of harm associated with psychedelics in non-regulated or poorly supervised conditions. For instance, a 22-year-old man reportedly died at a retreat with ayahuasca, a DMT-containing hallucinogen used in spiritual ceremonies. In another high-profile incident, a passenger attacked United Airlines crew members while high on psilocybin.

These anecdotes are quite rare, but perhaps, critics worried, they would become more commonplace.

Now, months after Colorado’s legalization, have any of the fears around increased violence and abuse been realized yet? Early data don’t appear to validate the critics.

Impact on public safety

Opponents of psychedelic legalization argue that law enforcement agencies–responsible for dealing with violent and disorderly people–don’t support it. Law enforcement opposition is cited to validate public safety concerns.

To explore whether this argument holds up, we contacted a few agencies and institutions that oversee health and safety for the densest county in Colorado, Denver. Our inquiries included the Denver Police Department and the district attorney’s office. We also reached out to other well-populated counties, including El Paso County.

As of yet, there has not been a single police agency that reports psychedelics as a public safety issue. “Psilocybin has not been a significant law enforcement issue in Denver either prior to or following the passage of Proposition 122,” wrote a representative for the Denver Police Department in a statement to me.

“I have checked with our Drug Task Force and Legal, and as of now, we have not seen any significant change or impact in our jurisdiction,” wrote a representative from Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department, but added that tracking incidences could be difficult because it’s not common to ask whether suspects are on psychedelics.

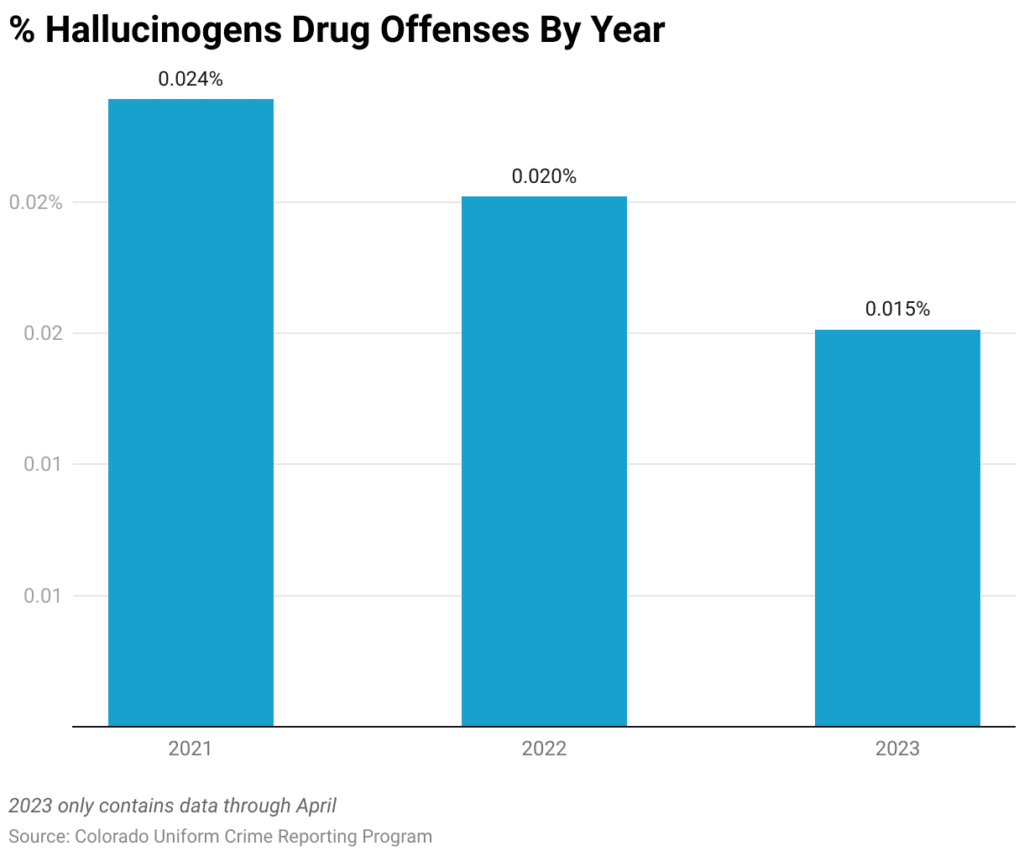

Statistics from the Colorado Uniform Crime Reporting repository reveal that there has not been a significant increase or decrease in the number of psychedelics-related crime incidents. In the first quarter of 2023, incidents in which the subject was intoxicated with or had possession of a hallucinogen represented just 2% of all of Colorado’s drug-associated crimes from the first quarter of 2021-2023 (because there is only partial data for 2023, we did not compare the entire years of 2021 and 2022).

However, these statistics could underestimate overall abuse. One staff member of an agency that oversees crime reports noted that psychedelics are a (relatively) small issue compared to an intoxicant like alcohol, so police departments don’t have a standardized way of documenting incidents. They don’t differentiate between psilocybin, mescaline, or DMT.

Additionally, because psychedelics are now legal, police could be arresting people less often or, at the very least, not documenting the possession of a now-legal psychedelic.

One exception would involve incidents of driving under the influence of psychedelics, which is still illegal. So far, in 2023, there have been only 20 recorded incidences in all of Colorado of driving under the influence (DUI) while on a hallucinogen (or 2% of 820 total drug-related DUI incidences). In the first quarter of 2022, there were 8 of 205 total incidents involving hallucinogens. To compare the nearest pre-pandemic year, there were seven incidents in 2019.

It should be noted that data is still coming in for the first quarter of 2023, and all precincts may not have fully tabulated and submitted their reports until later this year.

Public health

Another common metric for potential harms that follow the legalization of a controlled substance is the rate of hospitalizations related to intoxication or abuse. Critics have previously noted that there was a moderate increase in marijuana-related hospital visits following the legalization of adult-use cannabis.

We contacted two of the largest hospital systems in Colorado to see if similar trends followed the legalization of psychedelics.

“[T]he general consensus is that there has not been any noticeable changes” a media relations representative from HealthOne, a network of hospitals and clinics serving Denver wrote to me.

“Since proposition 122 passed last year, Denver Health has not seen an increase or decrease in incidences related to hallucinogens,” wrote a spokesperson for Denver Health, another network of medical and health organizations.

While still preliminary, a small sample of drug-related hospitalizations and emergency room visits for January 2023 from hospitals throughout the state confirm their experiences. Hallucinogens represent just 0.3% of drug-related incidences. By comparison, alcohol represents 54%.

The Colorado Hospital Association aggregates incidences recorded from hospitals; for the preliminary dataset provided to us, the data is all incidences that have co-occurred with descriptions of a drug (so, if, for instance, someone came in injured and drunk on alcohol, it would be recorded as an alcohol-related incident).

As we researched the data, several health professionals expressed misconceptions about what Prop. 122 actually did. As a result, they showed little interest in offering a statement on an issue that was such a trivial part of their job.

One representative of a health company wrote, “I think the important thing to note is nothing has changed yet in Colorado related to Prop. 122,” before declining an interview. They linked to an article explaining how state agencies will be charged moving forward with designing regulations for professionally guided psychedelic experiences. While it’s true that much of what Prop. 122 legalized is still yet to come, the initiative also immediately legalized personal possession of some botanical psychedelics but did not specifically outline rules around commercial therapeutic services (which are still legal gray territory).

So, while Colorado’s Proposition 122 was fiercely debated, the actual impact of psychedelics on those overseeing public health is much milder. Hallucinogens apparently have not been enough of an issue, before or after legalization, to merit much attention from law enforcement and medical professionals.

A random sampling of the impact of legalization

Surveying police departments, hospitals and psychedelic insiders can skew the data to make Prop. 122 more impactful than it actually is to most residents. Many people may never be impacted by it, positively or negatively.

So how are everyday Coloradans experiencing Proposition 122’s impacts? As part of this investigation, we conducted field convenience sampling interviews in Denver.

For the most part, at least in major cities, Coloradans had no opinion about Prop. 122. On one occasion, a young woman who was a psilocybin user touted the mental health benefits.

To operationalize this line of inquiry, we designed a two-part public opinion survey to better probe the personal experiences of everyday Coloradans. First, they were asked a simple question:

“In November 2022, Colorado voters passed Proposition 122, which legalized the personal possession of some plant-based psychedelics, such as psilocybin (‘Magic Mushrooms’). Has the change in law personally impacted you, a friend, or a family member in any way?”

Then, respondents were asked to provide details if they happened to have been impacted negatively or positively.

Below are the results of a small concept.* Only six (less than 10% of the 70 respondents of the small survey) noted an example of how legalization had impacted them. Invalid examples were excluded (nonsensical answers).

Six responses were positive, and one was neutral. Of those who had been impacted, one respondent noted: “I have a friend who microdoses for health-related reasons. They have much easier access to psychedelics due to the legalization.”

One neutral response noted, “My brother and I live around the Colorado Springs area and have both benefited from the legalization of marijuana but nothing has come from the legalization of psychedelics. I think decriminalization has made it safer for the community to do what they and ourselves were going to do already. We just don’t really do mushrooms very often.”

We are reporting on the results of this small poll to encourage feedback on the conceptual design of the survey. The very early results seem to be in line with the field interviews, but a much larger sample is necessary to make broader conclusions.

Anecdotal evidence and advertising bans

As part of our investigation, we also contacted critics of Prop. 122 and asked what types of data points we may have missed.

Critics noted that there are notable anecdotes that, at the very least, should be mentioned in the report, even though it would be difficult to collect quantitative data on incidents like erratic behavior. Critics also worry that consumers will have a professionally “guided” psychedelic trip that is badly administered (guides could give dosages that are too strong or not properly prepare novice users, for instance).

And, indeed, there are anecdotal reports of harms related to psychedelics in Colorado.

Mason Marks of Florida State University writes in Psychedelic Week that members of the public showed up to provide testimony for a bill that would limit Proposition 122. They described children who had been harmed after consuming psychedelics.

Additionally, as Colorado regulators work on codifying standards for professionally guided services, the law still permits largely unregulated service providers to give high-dose psychedelic experiences for therapeutic and spiritual purposes. It is common for professional guides to adhere to a set of unwritten but common standards, such as giving novice psychedelic users an educational ‘preparation’ session before their experience.

Our investigation did find one anonymous professional who believed that legalization increased the number of anecdotes about sub-substandard professionally guided trips. None of these anecdotes of unprofessional guided trips could be corroborated. Even though the evidence from this secondhand report is scant, we note it here because our investigation will represent the broadest possible array of views and concerns.

Ironically, the problem of subpar professionals could be a direct result of one of the few regulations over personal possession outlined in Proposition 122. The law bans professionals from advertising psychedelic services until the state implements its regulated framework.

Unfortunately, the ban on professional advertising inadvertently censors consumers. Most businesses have online review pages on the likes of Google Maps or Yelp. Under current law, consumers do not have any readily available and popular site to leave reviews of professional psychedelic guides. Indeed, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Eric Bryjolfsson has published research on how online reviews can provide important quality information to consumers over occupational licenses.

Colorado regulators may want to consider removing the advertising ban.

Conclusion

Preliminary findings reveal that the negative public health impacts of legal psychedelic possession in Colorado are negligible. The early results also appear similar to what happened in the Netherlands, where psilocybin is widely available and there are few reported harms.

*This survey had a sample size of 70 and an estimated margin of error: -/+11. It was conducted online and targeted individuals in Colorado using Amazon’s Mturk, a validated sample for political polling.