In the United States Court Of Appeals For the Ninth Circuit

In re: Any And All Funds Held In Republic Bank Of Arizona Accounts XXXX1889, XXXX2592, XXXX1938, XXXX2912, and XXXX2500,

United States of America,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

v.

James Larkin, Real Party In Interest Defendant; John Brunst, Real Party In Interest Defendant; Michael Lacey, Real Party In Interest Defendant; Scott Spear; Real Party In Interest Defendant,

Movants-Appellants.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California

This case presents questions of critical importance under the First and Fourth Amendments that are of great concern to amici. The Supreme Court has held that although “the general rule under the Fourth Amendment is that any and all contraband, instrumentalities, and evidence of crimes may be seized on probable cause . . . it is otherwise when materials presumptively protected by the First Amendment are involved.” Fort Wayne Books, Inc. v. Indiana, 489 U.S. 46, 63 (1989). In the case below, the government has ignored this admonition, seizing defendants’ assets and other materials that are presumptively protected by the First Amendment with neither a pre- nor a prompt post-seizure hearing. The government’s position appears to be that it is entitled to effect these seizures because the materials at issue are not actually protected by the First Amendment. But the government has it backward. Proving that the materials are not protected by the First Amendment through an adversarial hearing is what the government must do before it is entitled to take them.

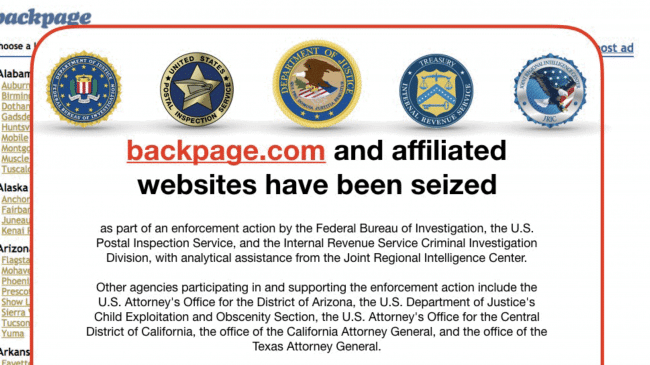

Amici write to amplify the danger that the government’s use of civil forfeiture to seize the assets and proceeds of expressive material poses to free expression. The government has shut down a major internet site and confiscated millions of dollars of assets and proceeds not only from that site, but also from defendants’ numerous other publishing ventures—ventures completely unrelated to the alleged criminal activity of the site and indisputably protected by the First Amendment. And the government has done so on nothing more than its say-so that the site and the assets and proceeds are not protected by the First Amendment. Absent any meaningful judicial check on the government here, nothing can stop it from going after other internet sites that it deems unworthy of First Amendment protection, as well as any assets held by those who own the sites. Although the government attempts to evade judicial review of its actions by this Court, judicial vigilance should be at its height when the First Amendment is at stake.

Expressive materials—such as newspapers, books, and their internet analogs—are presumptively protected by the First Amendment. And this presumptive protection extends to the assets for producing such material, as well as the proceeds from their dissemination. The First Amendment’s protections must reach such assets and proceeds to preserve the integrity of the marketplace of ideas; for if the government can selectively deprive certain speakers of the financial incentive to speak, then the government can silence the speakers themselves. The burden for rebutting the presumptive protection that all expression enjoys rests with the government. It is a heavy burden, as it must be to ensure the protections of the First Amendment. The government, then, can only seize expressive materials— including the assets and proceeds associated with expressive materials—if they are unprotected by the First Amendment. And the government must first demonstrate that the materials are not protected, as a matter of law, in an adversarial proceeding.

The government did not seize the defendants’ assets and proceeds after an adversarial proceeding—or any proceeding at all. Instead, it usurped a role meant for an impartial arbiter, by simply assuming that these assets and proceeds were not protected by the First Amendment.

Unfortunately, the government’s conduct here is not new. The history of government efforts to suppress and censor disfavored speakers, particularly speakers who offer sexually explicit expressive materials, is long. Along with overseeing censorship boards and organizing adult bookstore raids, the government has previously mounted a multistate prosecutorial campaign designed to intimidate the adult entertainment industry into silence. See United States v. PHE, Inc., 965 F.2d 848 (10th Cir. 1992). This campaign involved tactics similar to those employed here, designed to bankrupt speakers by forcing them to litigate on multiple fronts to prove that their speech is protected by the First Amendment. Throughout this history, however, the government’s efforts to silence these speakers largely have been thwarted by the Supreme Court’s clear instruction on the breadth of the First Amendment and the limits of government censorship over protected speech.

This Court should follow the Supreme Court’s instruction and deem the government’s seizures unconstitutional under the First and Fourth Amendments.