America’s economic pundits are not very creative. For the past several years, their gripes about economic growth have fallen into several staid categories: Monetary policy (“the Fed should do less” vs. “the Fed should do more”); the struggling housing market (“let housing bottom out” vs. “we must save housing”); income inequality (“it doesn’t matter” vs. “it does matter”); and the federal deficit (“lower taxes, pretend to lower spending a lot” vs. “raise taxes, pretend to lower spending a little”).

While most of these are legitimate causes of economic stagnation, there is another category that is having an outsized negative impact on growth: privately held debt.

The housing bubble should have been the warning needed to correct American thinking on debt, but the media’s positive spin on reports that borrowing is “coming back” suggest the lessons have not been learned.

The concept of debt has a troubled history. Historically when debts accumulate to a breaking point, the associated social unrest can lead to revolution and insurrection. This sociological trend gave rise to the Occupy Wall Street movement, particularly regarding debt from student loans.

However, debt isn’t inherently a bad thing. Innovation in the past three centuries has sped up societal evolution and technological breakthroughs at breakneck speed compared to the last 5,000 years, and much of this has been built on borrowing and lending.

Entrepreneurs with ideas often don’t have the capital to launch their business, and organizations with capital often don’t have the ideas to grow that money on their own. The beauty of finance is that we have developed tools to connect these two groups so that the entrepreneurs and capital investors have mutual benefit.

The biggest challenges of debt come when loans are taken out irresponsibly (like no income, no job mortgages), when money is borrowed for consumption rather than investment (like excessive credit card debt), and when lenders are guaranteed a return of their money by law even in the case of bankruptcy (like student loans that are not discharged in bankruptcy, one of the leading reasons for the Occupy complaints).

Unfortunately, all of those examples of irresponsible borrowing and lending are from the past few decades in America. Since the mid-1990s, privately held debt has soared to record highs. Promises that housing prices would rise forever deluded households into taking out big mortgages. At the same time a bull market in equities and low interest rates for several years made the costs of borrowing appear inconsequential.

Many borrowers believed their debt was for a good investment (and therefore “good” debt), or weren’t concerned about taking on a high mortgage or big credit card balances because perpetual economic growth would solve all the problems. But the bursting of the housing bubble left households with high levels of debt to deleverage or to take into bankruptcy court.

This part of the story is well known in towns across the country, but what is not widely recognized is that this debt level is also preventing the private sector from rebounding after the recession.

For those who believe that the problem in the economy is aggregate demand, high debt levels mean households are limited in what they can contribute to consumption. Even if stimulus was able to build a bridge through a recession, the historically high levels of debt have years of deleveraging ahead of them, keeping consumption off the table as a way of spurring recovery.

For those who believe that aggregate supply could boost growth, small businesses too are saddled with having to pay the bill for decades of fun since many are linked to individuals and households, and therefore don’t have the capacity to invest at levels needed for a robust recovery.

Washington has tried to solve this problem by encouraging more borrowing to get the music going again. Public support for more quantitative easing is primarily focused on pushing down interest rates so that businesses and households will borrow again. The Federal Reserve’s purchases of housing debt are about lowering mortgage prices so households will borrow again to buy homes.

This has led to the media buying into the idea that if only Americans could borrow again, aggregate demand and supply would bounce back. An article from Businessweek on Monday referenced recently increased bank lending as “supporting” economic growth.

This is totally backward thinking. Literally.

Recovery should not be defined as moving backward to the way the economy used to be structured. That was a bubble, built primarily on cheap credit and not long-term investments.

Moreover, much of the recent borrowing increases have been in revolving credit, primarily credit card debt, in order to meet basic needs. That is not the kind of consumption that will generate a recovery, especially since the costs of credit card debt are high and will weigh back down on household balance sheets in the months and years to come. A recovery built solely on expanding consumer credit and mortgage credit is simply another bubble and unstable economic foundation.

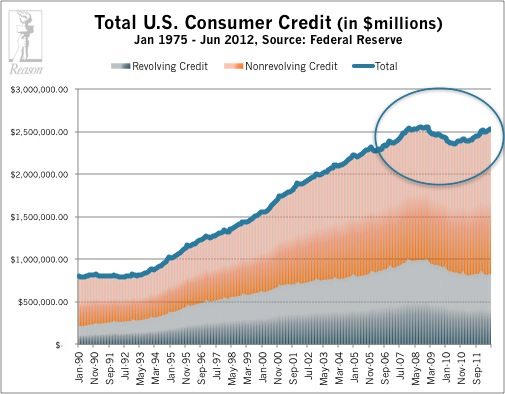

America had started the process of household balance sheet deleveraging after the bubble burst. Mortgage debt levels have fallen sharply. And consumer credit-all debt other than mortgage debt-was declining as well. But in the summer of 2010, as the post-recession faux-recovery created false hope that the good times were back and as savings decimated by the bursting bubble began to hit zero in the midst of a weak economy, consumer credit levels (led by credit card purchases) began to rise again.

The figure below shows that consumer credit fell 7.1 percent from June 2008 to June 2010, but since then has grown 6.9 percent to June 2012 (according to data released this month by the Fed).

The rising aggregate consumer credit level means that household balance sheets are not shedding debt like they need to in order to contribute substantively to economic growth. Unless this changes, we’repretty much screwed.

High household debt means less economic and labor mobility. Families cannot move to better employment if they are stuck in a house they cannot sell or have credit card bills crushing their credit score and making it harder to move. Private sector debt also means fewer family vacations, no upgrades on household appliances, and less investment.

Perhaps most damning is that households deep in debt mean downward pressure on entrepreneurial expansion. Many small businesses are family run, or are financed from household balance sheets. As long as entrepreneurism is stagnant, the U.S. economy is not going to see real growth.

Rather than public policy seeking to make borrowing cheaper, American leaders need to allow for household balance sheets to deleverage. That will mean short-term economic pain in exchange for a more robust economic growth period on the other side. And since the economy is in stall mode currently, the directly-associated pain will be muted anyway. Both President Barack Obama and his Republican opponent Mitt Romney are kidding themselves if they think they can inspire a recovery in the next several years without consumer credit levels falling and household debt levels coming down.

Anthony Randazzo is director of economic research for Reason Foundation. This commentary first appeared at Reason.com on August 9, 2012.