- FHWA guidance on highway expansion sparks backlash

- How the new federal bridge program rewards failure

- House committee disappoints on automated vehicle innovation

- Who gets RAISE grants, and why?

- Semantics of mileage-based user fees

- News notes

- Quotable quotes

FHWA Guidance on Highway Expansion Sparks Backlash

Last month’s newsletter article about Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Acting Administrator Stephanie Pollack’s guidance memo urging state departments of transportation (DOTs) to give the lowest priority to highway capacity expansion (and promising tough environmental reviews if they do select such projects) has stirred up a hornet’s nest. In recent weeks I’ve heard from state transportation officials from red and purple states who are outraged by this attempt to rewrite the formula-funded majority of the bipartisan infrastructure law. The Wall Street Journal published a hard-hitting editorial on Jan. 30, “Highway Funding Bait-and-Switch,” which pointed out that such anti-highway policies were included in the House surface transportation reauthorization bill last summer, but that bill was replaced by the bipartisan Senate bill, which became law.

In addition, a group of 16 Republican governors recently released an open letter to President Joe Biden and the U.S. Department of Transportation, writing, “Excessive consideration of equity, union memberships, or climate as lenses to view suitable projects would be counterproductive. Your administration should not attempt to push a social agenda through hard infrastructure investments and instead should consider economically sound principles that align with state priorities.” A clear example would be “an attempt by the Federal Highway Administration to limit state widening projects, which would be biased against rural states and states with growing populations.” Signers of the letter were mostly from rural states, but Republican governors fast-growing Georgia, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Utah were also among them while other notable fast-growing states with Republican governors—Arizona, Florida, and Texas—did not sign on to the letter.

During her Senate confirmation hearing as Office of Management and Budget (OMB) director last week, Shalanda Young told senators that she was not aware of the FHWA guidance letter and would look into it. Eno Center for Transportation’s Jeff Davis pointed out that most such policy proposals are supposed to be submitted to OMB for review prior to being issued. He also noted that dismayed senators could ask the Government Accountability Office to look into whether the guidance letter is subject to being overturned via the Congressional Review Act.

What kinds of projects are on tap in fast-growing states? Here is a sampling.

Replacing Bottleneck Interchanges

Each year, the American Trucking Associations releases a list of the 100 most congested interchanges for truck travel—mostly where urban Interstates connect with other major highways. Many of these interchanges handle as much as double the traffic they were designed for many decades ago. Among those in current transportation plans are:

- Florida: The huge Golden Glades interchange in Miami, where I-95, Florida’s Turnpike, the Palmetto Expressway and U.S. 441 all interconnect.

- Georgia: Several major interchanges on the I-285 Perimeter, the ring road around central Atlanta.

- South Carolina: Malfunction Junction (aka the Carolina Corridor), where I-20, I-26,and I-126 intersect. The first phases of this $1.7 billion project are already under way.

These projects would reduce congestion, and hence greenhouse gas emissions, and benefit cars, trucks, and buses alike.

Widening Expressways Overloaded Due to Growth

These widening projects are needed not only in fast-growing Sunbelt states but also in blue states like Illinois where suburban growth has overloaded expressways originally designed for commutes to downtown areas.

- Illinois: The state DOT has large-scale support to rebuild the aging Eisenhower Expressway (I-290), including the addition of express toll lanes and replacement of many structurally deficient bridges.

- North Carolina: Work is under way to complete the planned Outer Loop around I-540 in Raleigh. In this case, the project is being developed using toll finance.

- South Carolina: SCDOT’s 10-year plan includes widening I-85 in Greenville and Spartanburg counties, again due to recent and projected growth.

Bridge Replacements

Many major bridges have outlived their original design lives, and some of these bridges have fewer travel lanes than the highways on either side, meaning the bridge itself has become a bottleneck. These projects include:

Alabama: Replacing the Mobile River Bridge with a higher span to provide improved clearance for cargo vessels passing underneath.

Kentucky: Replacing the obsolete Brent Spence Bridge, to be partly funded by tolls.

Louisiana: Replacing the Calcasieu River Bridge on I-10 with a six-lane toll bridge.

Oregon: Replacing the obsolete I-5 bridge across the Columbia River between Portland and Vancouver, WA.

Missing Links

A number of freeway systems have missing links that were not built for a variety of reasons, including local opposition, but whose absence has led to congestion and emissions in the non-freeway locations. One example is the missing link in Ft. Lauderdale, where the Sawgrass Expressway was supposed to extend several miles further east to connect with I-95. Political support for it has developed as the region has grown, and this project is now in the design phase by Florida DOT.

State DOTs with well-defined needs for projects like these are not going to give up, just because FHWA has implied that it may make their lives difficult. And although projects like these are mostly in red states, there are enough of them in other states to make possible 2023 congressional action to rein in FHWA on its anti-expansion game plan.

How the New Federal Bridge Program Rewards Failure

In the new bipartisan infrastructure law, Congress included $27.5 billion over five years for bridge repair and replacement. According to the federal bridge inventory, the number of bridges in “poor” condition (structurally deficient) was 43,578 in 2021, down 3.2% from the year before. That’s because some state transportation departments, with support from their legislatures, are taking their bridge conditions seriously. Other states, however, are not. In many cases, the fault lies largely with state legislatures, not DOTs. In other words, as I’ve written before, we don’t really have a national bridge problem: we have a number of state-specific bridge problems.

As Reason Foundation’s Baruch Feigenbaum noted in his incisive analysis of the recent bridge collapse in Pittsburgh, “Pennsylvania is one of five states that reported more than 15% of their bridges to be structurally deficient…the problem isn’t that Pittsburgh lacks the funding to fix bridges. Rather, the problem is the way the city spends so much of its annual budget on other things and chooses to spend so little of its money maintaining its roads and bridges.”

A useful overview from the American Road & Transportation Builders Association (ARTBA) lists the states with the largest fraction of bridges in “poor” condition (as defined by a widely accepted numerical rating system). Here are the 10 worst states, by this measure:

| West Virginia | 20% poor condition |

| Iowa | 19% |

| Rhode Island | 17.5% |

| South Dakota | 17.3% |

| Pennsylvania | 13.8% |

| Louisiana | 12.8% |

| Maine | 12.6% |

| Puerto Rico | 12.1% |

| North Dakota | 11.2% |

| Michigan | 11% |

The new Bridge Formula Program (BFP) allocates money to each state via a formula, which is based 75% on the total cost of replacing every bridge rated “poor” in a state and 25% on the total cost of replacing every bridge rated “fair” in that state. In other words, the more that a state has neglected its bridges, in terms of a huge repair backlog, the more the bridge program rewards it. In a well-researched piece for National Review, Dominic Pino ranks all 50 states (plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico) on their unit costs of bridge replacement (cost of replacing bridges rated poor divided by the deck area of those bridges), finding that a disproportionate share of the BFP funding will go to high-cost states, such as California, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Connecticut. California alone is allocated 16% of the total bridge funding. Texas, with relatively low bridge replacement costs and bridges in much better condition, gets far less. Here are the 10 largest allocations of BFP money for FY 2022:

| California | $849 million |

| New York | $378 million |

| Pennsylvania | $327 million |

| Illinois | $275 million |

| New Jersey | $229 million |

| Massachusetts | $225 million |

| Louisiana | $203 million |

| Washington | $121 million |

| Michigan | $113 million |

| Connecticut | $112 million |

State and local governments own nearly all of America’s bridges. To be sure, most of them could be investing more in proper stewardship of these important assets. But this new $27.5 billion federal bridge program serves as bailout, as Pino notes, that “rewards states that waste more money with more federal aid.” And perhaps worse, every one of those federal dollars comes with costly strings attached, in particular Buy America provisions and Davis-Bacon prevailing wage requirements. Those extra costs do not apply when states use their own highway funds for bridge repair and replacement.

One-time windfalls like this federal bridge program implicitly encourage state legislatures to devote the majority of their highway funds to projects with ribbon-cutting opportunities (generally many small new-capacity projects). Legislators can then try to excuse their neglect of ongoing maintenance by reviewing history—every decade or so, in hopes that some kind of federal bailout comes along that can compensate for their years of neglect.

House Committee Disappoints on Automated Vehicle Innovation

By Marc Scribner

On Feb. 2, the House Transportation and Infrastructure (T&I) Committee’s Subcommittee on Highways and Transit held a hearing on “The Road Ahead for Automated Vehicles.” Technology has changed since the last T&I hearing on automated vehicles (AVs) nearly a decade ago, but the members and non-developer witnesses appearing on the panel generally failed to reflect—or at least reflect accurately—the changes in the AV landscape. With Congress out to lunch and an administration at best indifferent to AVs, the near-term prospects for a comprehensive federal automated vehicles policy framework remain slim.

The hearing’s eight witnesses made for an unwieldy proceeding. Only two of them represented developers of the technologies that were the subject of the hearing, with the remaining witnesses representing “stakeholder” interests with various hobby horses and axes to grind. These included two labor union representatives, John Samuelsen of the Transport Workers Union, and Doug Bloch of the Teamsters, who unsurprisingly expressed general opposition to automation. They urged legislators to prioritize the perpetual employment of their dues-paying members over all other considerations, including safety, with Samuelsen bluntly saying, “No level of vehicle automation should ever replace them.”

Samuelsen also made an historical reference that didn’t seem to register with any members in attendance, even though it highlighted the main reason why U.S. transit agencies cannot adopt automation. He mentioned that “the New York City subway ran a fully automated train across Manhattan from 1962 to 1964.” Train automation proved very popular with New Yorkers, but was scuttled largely due to union opposition during a turbulent time for transit in America.

The transit industry was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy in the early 1960s. The federal government sought to finance municipal takeovers of these private companies to preserve transit service in cities. In exchange for the support of powerful transit unions, lawmakers added Section 13(c) to the Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1964. This provided transit unions and their members with iron-clad job protections that exist to this day (49 U.S.C. § 5333(b)).

The inflexibility of Section 13(c) is why it is very difficult for U.S. transit agencies to reduce labor costs in general (see the Biden administration’s rekindling of a dispute over California’s modest 2013 public pension reforms, for example) and functionally impossible through automation, even if automation would improve transit safety, reliability, and access. As a practical matter, unless Section 13(c) is significantly weakened or repealed by Congress, U.S. transit agencies are unlikely to adopt life- and cost-saving automation.

On the other side, Nat Beuse from Aurora brought the perspective of both an AV developer and a former motor vehicle safety regulator. Before entering the automated vehicle industry in 2019, he was a senior official at the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) for nearly 20 years. Beuse reminded the panel that AVs, like any other motor vehicle, are subject to many federal, state, and local regulations. He also emphasized that Aurora’s AV testing protocols allowed any employee to request a halt to automated vehicle operations, and that the company runs millions of simulations each day before attempting to validate its software on public roads. He urged Congress to ensure that laws and regulations for AVs are technology- and business model-neutral.

The other AV industry representative was Ariel Wolf, who leads the newly renamed Autonomous Vehicle Industry Association. He was clear in drawing an important distinction between advanced driver-assistance systems, such as Tesla Autopilot, and the automated driving systems under development by Wolf’s members. When Rep. Hank Johnson (D-GA) conflated Tesla’s approach with that of the entire industry, Wolf responded, “Tesla is not a member of our association because it’s not an autonomous vehicle. It’s a driver-assistance technology.”

Wolf’s trade association until January was called the Self-Driving Coalition for Safer Streets. Tesla refers to its most advanced automation features as “Full Self-Driving Beta.” Tesla’s approach has been criticized as reckless by those inside and outside the AV industry, and the term “self-driving” has been tainted in the eyes of many.

In questioning Wolf, Rep. Johnson mentioned a recently deployed feature within Full Self-Driving Beta that is designed to allow users the option to slowly roll through all-way-stop intersections under certain low-risk conditions. Technologist Brad Templeton makes a good case for this feature’s existence, but the problem is that rolling stops are illegal in every U.S. jurisdiction. So, Tesla voluntarily agreed in January to disable the rolling stop feature through an over-the-air update.

Tesla ultimately gained nothing through its rolling stop release other than needlessly antagonizing Biden administration officials, who have unfortunately shown much less interest in the large potential safety benefits of AVs than their predecessors in the Trump, Obama, and Bush administrations. In June 2021, NHTSA issued a sweeping Standing General Order requiring all AV developers to report crashes to the agency, which was almost certainly in response to Tesla’s behavior alone. It is no wonder the rest of the AV industry is seeking to distance itself from Tesla.

The four-hour hearing offered disappointingly little in terms of policy substance. For those who have followed federal AV hearings in Congress during the last decade, the overwhelming feeling was one of déjà vu. Outgoing T&I Chair Peter DeFazio (D-OR) correctly noted, “It’s going to be an extraordinary challenge for regulators” if the U.S. is to realize the “whole host of benefits just waiting out there.” But this sentiment has been expressed for years with no action to back it up. States and federal regulators are now charting their own automated vehicle policy paths without any meaningful guidance and oversight from Congress. This isn’t likely to change in 2022, but maybe there is hope in a new Congress in 2023.

Who Gets RAISE Grants, and Why?

By Baruch Feigenbaum

RAISE is the acronym for a federal grant program, Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity. Since the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 created the Interstate Highway System and provided federal funding for surface transportation, the majority of funding has been awarded based on complex formulas. Over the last 30 years, leaders of the funding and transportation committees have become very skilled at writing formula funding that benefits their districts and/or states. I was thrilled when the George W. Bush Administration created the Urban Partnership Agreement (UPA) and Congestion Reduction Demonstration (CRD) grants that awarded six projects funding based on quantitative metrics.

Any projects that receive federal transportation discretionary funding should meet the following four basic criteria:

- The project is evaluated based on a cost-benefit analysis.

- The project funds interstate infrastructure.

- The grant funds a transportation project.

- And, the project is not chosen for political reasons.

Unfortunately, discretionary grant programs from the Obama and Trump administrations were often designed more for political and policy reasons. How do the new RAISE grants rate? My intern Mae Baltz and I created a speadsheet heet that included all 763 grant applications. We examined how the 90 projects that were awarded funding differed from the 673 projects that did not receive funding. We categorized each project into national interest or local interest, transportation-related or not transportation-related, and whether or not the project is in a congressional district of members serving on a transportation or funding committee (the House Transportation and Infrastructure, House Ways & Means, Senate Banking, Senate Commerce, Senate Finance, Senate Environment and Public Works) or not in one of those districts. We also examined the federal share of funding and the type of applicant.

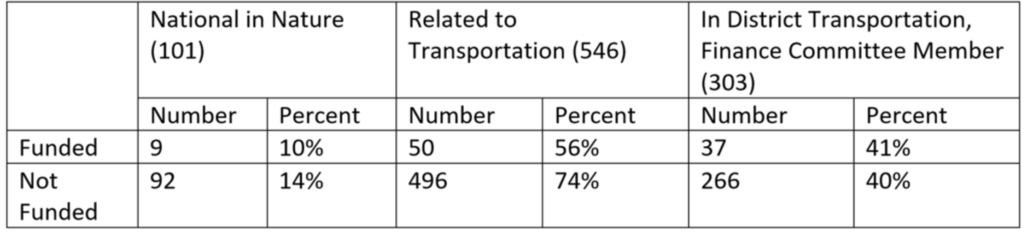

As the summary table shows, Reason Foundation fount that of the 90 projects funded with RAISE grants in 2021, only nine projects (10%) were national in nature.

Of the 90 projects funded by RAISE grants, only 50 projects (56%) were related to transportation.

The other projects funded were primarily focused on environmental remediation, economic development, or other factors. Of the projects not selected for the grants, 496 (74%) were related to transportation.

Reason’s review of the 90 projects funded found that 41% of RAISE grants projects were located in congressional districts represented by members of a transportation or financing committee.

Only 15 of the 90 projects funded (17%) by RAISE grants were projects submitted by state governments. While state governments don’t have the monopoly on good transportation ideas and projects, they do own the vast majority of the nation’s transportation infrastructure, including, most notably, Interstate highways that are in desperate need of reconstruction.

Breakdown of 2021 RAISE Grants

Source: Calculated by Reason Foundation’s Feigenbaum and Baltz using data from RAISE grants website

Not only did the projects that were funded with RAISE grants seldom meet the four basic criteria above, the projects that were not funded were more likely to meet those four criteria. In other words, the U.S. Department of Transportation was more likely to fund projects that were local, that were not related to transportation, and were located in the district of a politically-connected member of Congress.

What types of projects were funded? I’ve chosen a sampling of questionable projects based on the original intent of the program:

- $21 million to Little Rock, AR, to build a recreational trail to increase tourism and create economic stimulus

- $11 million for a multimodal transit center in Yuma, AZ, where less than 0.5% of commuters (or 1 of every 200) use mass transit

- $17 million to make Washington Street in Denver “livable” by adding streetscaping and energy efficient lighting

- $3 million to Trinidad, CO, to subsidize the La Junta passenger rail line, a line which received $15 million during the TIGER Grants

- $22 million to build recreational trails along the Atlanta BeltLine

- $10 million for New Jersey to revitalize Atlantic City—something the state has been spending money on without success for 40 years

- $25 million for Johnstown, PA to, in the words of the application, “Connect our history to the modern renaissance of art in the Johnstown community”

There were some good projects funded. South Dakota, for example, received $22 million for a freight rail expansion project and Bangor, ME, received $2 million to improve the I-95/SR 15 interchange. But there were almost as many projects studying the removal of Interstate highways as projects that improved highways.

The last three presidential administrations have shown that the executive branch frequently does not allocate discretionary federal grants to their highest and best uses. A program originally intended to improve mobility is getting further and further away from its purpose.

Going forward, the Congressional Budget Office and Congressional Research Service need to investigate where and how these discretionary grants are being awarded. And members of Congress need to use oversight power more effectively to determine why the executive branch is directing this taxpayer funding to non-transportation projects and why so much of it ends up in the districts of members on transportation and/or finance committees.

Semantics of Mileage-Based User Fees

Last month, the Government Accountability Office published an overview of the ongoing federal program that assists state transportation departments (and sometimes coalition of state DOTs) to test and evaluate ways of charging highway users by the mile instead of by a tax on gallons of motor fuel used. It’s GAO-22-104299, released last month.

For someone wanting to get up-to-speed on which states and coalitions have carried out pilot projects, the different methods they have tried out, and what they have learned, the report is an excellent overview. For example, I learned that only 11 of the 50 states have not either carried out a pilot project or been part of a multi-state coalition without directly operating such a program itself. The also-rans are Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia in the South plus Illinois, Iowa, Indiana, Michigan, South Dakota, and Wisconsin in the Midwest.

The report also includes some researchers’ speculations about addressing equity by having mileage fees that are somewhat proportional to income (which has never been seen as a need with per-gallon gas taxes) or that differ between urban and rural drivers, even though the latter have been found in study after study to be made better off in a shift from gas taxes to MBUFs, since rural users on average drive older and lower-mpg vehicles.

But my biggest concern is the language used in the section discussing privacy. At several points in that discussion, the text refers to GPS systems “tracking” people’s miles driven as the main privacy concern of motorists. Mass media have carelessly used that word, too. And even the academics at the Mineta Transportation Institute, in their public opinion surveys about mileage-based user fees, describe them as a system that would track their miles driven.

That wording reflects the widespread misunderstanding of what GPS is and does. The GPS in a device plugged into the on-board diagnositics port under your dashboard tells you where you are at any time. It does not tell this to anyone else—unless it is connected to a communications device to send that information elsewhere. In most mileage-based user-fee pilot programs, the mileage total is recorded by the device. That total can be reported to a designated service provider if and only if you agree to that being done. And that reporting can be as infrequent as once a month, reporting the total miles driven, not the details of when and where. In some situations (e.g., if you often travel across a state border), it may be necessary to record totals separately for each state—something that is being worked out between several western states in one of the multi-state pilots.

Recording and then reporting mileage totals is not “tracking” in the sense people imagine when they hear the term. They are likely to think something like, ‘big brother is in my car.’ That term tracking often fuels the privacy concerns that are probably the single most important obstacle to gaining public support for the needed shift from per-gallon taxes to per-mile charges. Everyone involved with efforts to bring about this change should remove the word “tracking” from their vocabulary when writing and talking about mileage-based user fees.

Mississippi River Bridge in Baton Rouge to be P3 Project

Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards has endorsed using a long-term public-private partnership (P3) to finance, develop, and operate a $900 million new bridge across the Mississippi in Baton Rouge. It would supplement existing bridges, including one on I-10, relieving major traffic congestion in that metro area. The governor proposed using up to $500 million in surplus state funds to cover half or more of the estimated cost of building the bridge. Louisiana Transportation Secretary Shawn Wilson is planning to begin the process via a pre-development agreement that would augment the needed environmental study.

First Kansas Express Toll Lanes Moving Forward

December 2021 saw the release of the environmental assessment of the planned addition of express toll lanes to 10 miles of U.S. 69 through Overland Park, Kansas. The study found minor impacts to wetlands plus increased noise exposure, calling for noise walls along certain stretches. The study was conducted jointly by the Kansas DOT and FHWA. The comment period closed on Jan. 22. Construction is expected to begin in mid-2022, with the toll lanes opening by 2025.

Sticker Shock Over Caltrain Electrification Estimate

Caltrain is the commuter rail line that connects Silicon Valley to downtown San Francisco. The agency announced that its latest cost estimate to electrify this line (replacing diesel locomotives) has increased to $2.44 billion. That sum covers 52 miles from San Jose to San Francisco. The increase results from an agreement with contractor Balfour Beatty to settle increased costs due to commercial issues and a schedule change. The project is aiming to be completed by Sept. 2024.

Brightline Hopes to Start Los Angeles to Las Vegas Line by End of Year

The Las Vegas Review-Journal reported that Brightline expects to break ground on the route between Las Vegas and Rancho Cucamonga by the end of 2022. Over the past year, Brightline has reached a right of way agreement to run the line alongside I-15 for most of the way, where it will terminate at a planned new station in Cucamonga, where passengers can connect to an existing commuter rail line. The 260-mile Las Vegas to Los Angeles trip is estimated to take 3 hours, an average speed of 87 mph. The current cost estimate is $8 billion, but no details of the planned financing have been announced.

TuSimple Expands Autonomous Trucking Operations in Texas

The autonomous trucking company announced an agreement with commercial developer Hillwood for a million square foot facility in Hillwood’s planned 27,000 acre AllianceTexas development. The facility is intended to be a depot for Level 4 autonomous trucks. The location is just off I-35, near Ft. Worth’s Alliance Airport and facilities of TuSimple’s main freight partners, UPS and DHL.

New I-5 Bridge Between Oregon and Washington Moving Forward

Discussions are under way on both sides of the Columbia River in the latest attempt to replace the aging and obsolete I-5 bridge. The I-5 Bridge Replacement Program staff are doing workshops with citizens, reviewing design alternatives such as two separate bridges (northbound and southbound) or a single double-deck bridge. Tolling appears to be a given, to cover a portion of the estimated $4.8 billion price tag. The current plan is to begin tolling as early as 2025, long before the new bridge is constructed.

Miami Causeway Project May Be Revived as a P3

The Miami-Dade County Commission voted to cancel the current request for proposals and start over on a potential P3 to modernize and enhance the Rickenbacker Causeway linking Miami with affluent Key Biscayne. A consultant value-for-money analysis found that a design-build-finance-operate-maintain (DBFOM) public-privage partnership would “minimize the county’s financial risks and financial obligations.” The next step is to seek a consultant for a project development & environmental (PD&E) study of the project, for which the county will be seeking partial federal funding. Once the project has been designed, the county would be prepared to resume a P3 procurement process.

Kansas Turnpike to Go Cashless by 2024

The Kansas Turnpike Authority is moving forward with replacing transponder-only lanes at toll plazas with full overhead gantries for all-electronic tolling. Those without transponders (called KTags) will be billed based on their license plate numbers. CEO Steve Hewitt told KVOE News last month that cashless tolling will go live up and down the highway at the same time in 2024.

$118 Billion Additional Bailout of the Highway Trust Fund

In a little-noted provision of the bipartisan infrastructure law, Congress approved borrowing another $118 billion to cover the projected shortfalls in the federal Highway Trust Fund over the next five years. Thus, users of all federal-aid highways will be paying an even smaller share than before in highway user taxes that were originally the sole funding source for the federal highway program. Users-pay/users benefit continues to morph toward taxpayers pay, highway and transit users benefit. Prior to this new bailout, since 2008 Congress had bailed out the HTF to the tune of $270 billion.

Walmart and FedEx Go All-in for Electric Delivery Fleets

GM electric truck division BrightDrop had an excellent January. Its first customer, FedEx, increased its original order for 500 delivery vehicles to 2,500. And Walmart topped that with a first-time commitment to purchase 5,000 electric delivery vans. BrightDrop’s first actual deliveries took place in December: five electric delivery vans for FedEx. BrightDrop estimates that these vehicles will save owners $7,000 per year in operating and maintenance costs, compared with internal combustion engine vans.

Alternative Proposal for LaGuardia Airport Rail Line

AmeriStar Rail (ASR), a startup company, has made an unsolicited proposal to New York state for an alternative to the currently planned two-link rail service from Manhattan to LaGuardia. Last Octover, the Port Authority suspended work on the FAA-approved Airtrain plan, which has local opposition, to give the new governor, Kathleen Hochul, time to review the plan. Last year ASR made an unsolicited proposal to take over Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor operations.

Kansas Studying Mileage-Based User Fees

Kansas DOT Secretary Julie Lorenz told the Topeka Capital-Journal that the expected long-term decline in fuel tax revenues will require eventually replacing fuel taxes with per-mile charges. Interestingly, she suggested that it may be best to have drivers on busy, congested highways pay a higher rate than those on local and rural roads, suggesting that we should be “thinking about transportation as a utility.”

St. Louis Faces Trolley Problem

What if you accept federal money to build a streetcar and then shut it down as not worth the money? That’s what St. Louis faces, with its federally-subsidized streetcar that’s been offline since Dec. 2019. But federal law requires that transit grant money be repaid if the project is not in operation. See Christian Britschgi’s report, “St. Louis Taxpayers Paid a Lot to Run a Money-Losing Streetcar. It Could Cost Them Even More to Shut It Down,” on Reason.com.

Michigan Proceeding with One-Mile of EV-Charging Road

Michigan has awarded a $1.9 million contract to Electreon to design and test-operate dynamic and stationary electric vehicle charging via a system embedded in up to one mile of roadway. It is billed as the first “electric road system” in the United States, according to a news release from Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s office.

Pennsylvania Diverted $4.2 Billion from Bridges to State Police

Instead of devoting its highway user taxes to roads and bridges, a 2019 audit found that $4.2 billion had been diverted to funding the state police. Reason.com’s Eric Boehm provides more details.

“Better Infrastructure Spending Needs Better Institutions”

A recent op-ed by Emil Frankel, a former state transportation director and senior official at U.S. DOT, makes a good case for methods and procedures to be in place at both state and federal levels of government, to ensure that projects selected for new federal funding are actually sound investments.

Overcoming Opposition to New Tolling

In a new one-pager aimed at public officials, I have suggested ways to address four main concerns about new tolling often raised by highway user groups.

“I was one of those who was part of the bipartisan negotiating team that put together the infrastructure bill. Our largest single investment was in highways. You can imagine our surprise when we see the Department of Transportation indicating that highway money can’t be used for increasing the capacity of highways. This direction flies in the face of our intent, and our needs. I recognize that there are some states that aren’t growing and may not need additional capacity—New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Rhode Island, and so forth. But there are other states that are growing fast—South Carolina, Florida, my state of Utah, fastest-growing state in the nation over the last decade. We need to increase the capacity of our highways or we’re gonna not see the economic growth which we projected as being part of this bill.”

—Sen. Mitt Romney (R-UT), in Jeff Davis’ “OMB Nominee Declines to Endorse New FHWA Policy Guidance,” Eno Center for Transportation, Feb. 3, 2022

“There are no transit routes now across the American Legion Bridge. This project will really change that, enabling our transit system to connect Maryland residents to Tysons or Virginia jobs, and vice versa. . . . This can be game-changing. In Virginia, there was no incentive to ever take a bus, because you sat in the same traffic as everybody else. Bus trips and carpooling in the Virginia express lanes have increased over 105 percent, on average, across the network since opening. I think the Virginia system has been able to show some of the naysayers how an express lanes network can fit into the broader transportation solution. Also we have pledged $300 million in transit services over the life of the Maryland project, to ensure transit is a core part of this project.”

—Pierce Coffee, in Katherine Shaver’s “Transurban Leader Calls Maryland’s Beltway, I-270 Toll Lanes ‘Transformative,’” The Washington Post, Dec. 30, 2021

“Over even a medium-term time frame, the increasing adoption of hybrid, electric, and autonomous vehicles will almost completely sever the connection between VMT and greenhouse gases. Those who are attempting to redesign cities, projects that will take decades or even centuries, merely to reduce the use of gasoline-powered cars, are thus engaged in a futile exercise that will only become more futile with time. It would be like trying to redesign cities in 1900 to reduce horse manure. The technology will change faster than the city will.”

—Judge Glock, “Sprawl Is Good: The Environmental Case for Suburbia,” Breakthrough Journal, Winter 2022

“Rarely in American history have states been in less need of federal aid. But they’re going to be getting more as portions of the $1.1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure law continue to roll out. The Bridge Formula Program is only one of many programs in the bill that will send money to states to fund the infrastructure they own and maintain—infrastructure they should be incentivized to fund on their own. Instead, inefficiency gets you more federal funding, while efficiency goes unrewarded.

—Dominic Pino, “The Bipartisan Blue-State Bridge Bailout,” National Review, Jan. 22, 2022