The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 70,630 drug overdose deaths for 2019 in the United States, 70.5 percent of which were opioid-related. Amid unprecedented drug-related mortality across the entire United States, Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) are the most popular interventions states enact to address opioid addiction and overdoses. Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs allow health officials and law enforcement to review the prescribing histories among doctors and patients in hopes of reducing inappropriate prescribing that might lead to addiction or death. However, the inception of PDMPs has been followed by increasing rates of opioid overdose and stable rates of drug addiction. With 19 years of mortality data, this analysis assesses whether Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs have significant effects on either opioid prescribing or mortality.

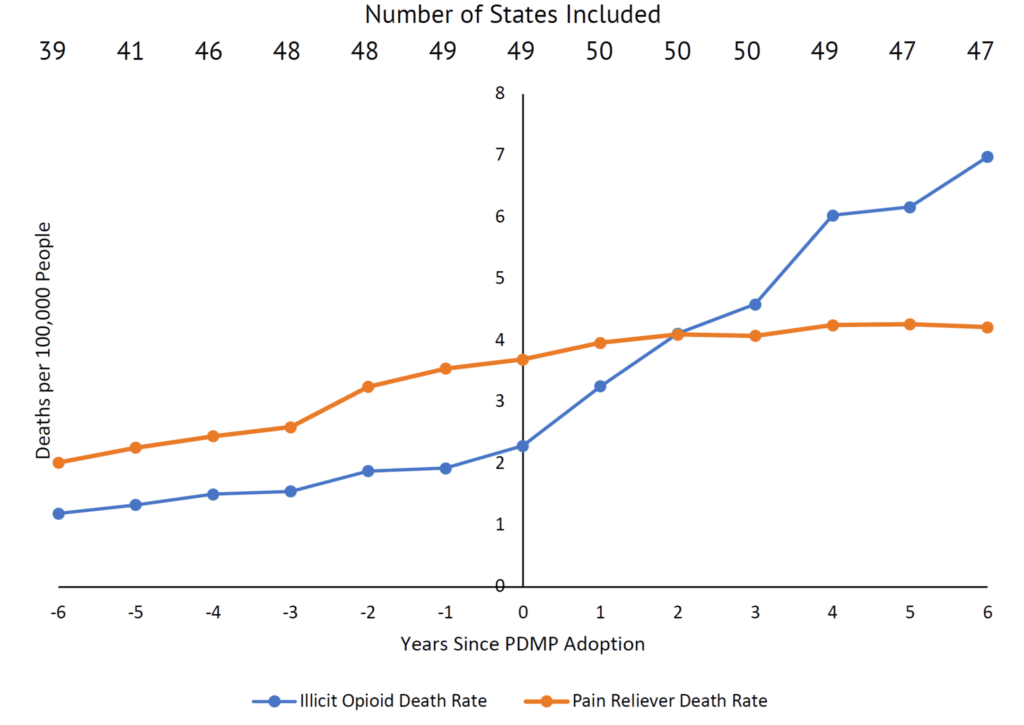

This study finds that, although Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs’ intermediary purpose to reduce prescribing has been achieved by reducing opioid distribution by 7.7 percent, they have had inconsistent effects on prescription opioid overdoses, while increasing total opioid overdoses by 17.5 percent due to increased mortality from the black market varieties by 19.8 percent.

FIGURE ES1: STATE-LEVEL DEATH RATES FROM LICIT AND ILLICIT OPIOID OVERDOSES FOLLOWING PDMP IMPLEMENTATION BY STATE

Source: “Multiple Cause of Death Data,” CDC WONDER

Since Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs fail to achieve their ultimate goal of reducing opioid overdoses, their funding should be re-appropriated to more effective mechanisms to reduce addiction and overdose rates, such as providing access to prescription-quality opioids for medication-assisted treatment (MAT).

Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) have been used in the United States since the early 20th century. Prior to 1914, natural opiates—the predecessors to modern synthetic or semi-synthetic “opioids”—were unregulated by the federal government and widely available for purchase without prescription in most of the United States.1Mark R. Jones, Omar Viswanath, Jacquelin Peck, Alan D. Kaye, Jatinder S. Gill, and Thomas T. Simopoulos, “A Brief History of the Opioid Epidemic and Strategies for Pain Medicine,” Pain and Therapy 7, no. 1 (2018), Accessed 18 August 2020 Use among the American public was quite commonplace. According to one article published in The New York Times, one in every 400 United States citizens had some type of opiate addiction by 1911, reportedly due to “the sudden emergence of street heroin abuse as well as iatrogenic [induced by medical treatment] morphine dependence.”2Edward Marshall, “Uncle Sam Is the Worst Drug Fiend in the World,” The New York Times,

www.nytimes.com, 12 March, 1911, https://www.nytimes.com/1911/03/12/archives/-uncle-sam-is-the-worst-drug-fiend-in-the-world-dr-hamilton-wright-.html, Accessed 18 August 2020; Jones et al., “A Brief History of the Opioid Epidemic and Strategies for Pain Medicine.”

In response to rising levels of Chinese immigration to the U.S., which was blamed for rising rates of opium use, states like California began outlawing the recreational consumption of various narcotics. San Francisco became the first U.S. municipality to enforce an anti-narcotics law in 1875, outlawing the operation of opium dens, which became state law in 1881. By 1907, California’s State Board of Pharmacy quietly lobbied for an amendment to the state’s poison laws, which prohibited the sale of opium, morphine, and cocaine except by a doctor’s prescription.3Dale H. Gieringer, “The Forgotten Origins of Cannabis Prohibition in California,” Contemporary Drug Problems, 1 June 1999

Eventually, the U.S. Congress passed the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act in 1914, the first federal statute regulating the production and sale of opiates and cocaine, which was enforced as a ban on the recreational sale of both products. Under this law, physicians across the U.S. were also restricted from prescribing opiates to addiction patients, and all proprietors of opium products needed to be registered with the federal government, creating the ancestor to the modern PDMP databases.

In an effort to further combat overprescribing, states slowly began to develop their own monitoring programs, the first of which was created in New York in 1918. However, these early PDMPs were rather slow in their collection speeds and used inefficient paper reports to monitor the prescription history of patients. 4History of Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs, Heller School for Social Policy and Management, Brandeis University, www.pdmpassist.org, 2018. https://www.pdmpassist.org/pdf/PDMP_admin/ TAG_History_PDMPs_final_20180314.pdf, Accessed 18 August, 2020

These programs developed throughout the mid-20th century and were rather ineffective, as “[p]rescribers were required to report to databases within 30 days, too long a time to reasonably be useful in preventing real-time ‘doctor shopping’ or over-prescribing.”5Claire Stoltz, The Effects of Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs on Opioid Use, Disability, and Mortality, Department of Economics, Harvard University, 2016 Additionally, there were no electronic databases tracking which patients had recently filled opioid prescriptions for doctors to reference.

Given the weaknesses of these early PDMPs, few states adopted any type of monitoring program over the course of the first half of the 20th century. However, the proliferation of PDMPs was greatly enabled by the ruling of Whalen v. Roe in 1977, a case that upheld the constitutionality of New York’s precursor of the PDMP under the broad police power given to the states by the Tenth Amendment. The plaintiffs of this case argued that the monitoring program constituted an invasion of patient privacy, due to its collection and storing of prescribing records. Writing for the majority, Justice John Paul Stevens held that, “[n]either the immediate nor the threatened impact of the patient identification requirement on either the reputation or the independence of patients…suffices to constitute an invasion of any right or liberty protected by the Fourteenth Amendment.”6Whalen v. Roe, 429 U.S. 589 (1977). With the constitutionality of patient prescription monitoring upheld, states were able to pursue data collection on prescribing history more thoroughly. Empowered by this ruling, many more states began to operate some form of a PDMP.

By 1990, states such as Oklahoma and Nevada began to adopt electronic reporting systems, greatly expanding the capabilities of these programs. These improvements reduced operations costs and increased the accuracy of the databases, leading other states to consider them as a viable means to monitor opioid prescribing.7History of Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs

In 2003, the PDMP seemed to be an effective way to combat opioid overdose deaths. Given that the majority of opioid deaths in 2003 were due to prescription drugs, the program’s intended purpose of limiting opioid prescribing seemed logical. In that year, Congress further increased funding for state PDMPs through the Harold Rogers Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs Grant, a competitive federal program that allows states to receive funding to “enhance the capacity of regulatory and law enforcement agencies and public health officials to collect and analyze controlled substance prescription data…through a centralized database administered by an authorized state agency.”8Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Assistance, Harold Rogers Prescription Drug Monitoring Program, www.bja.ojp.gov, 2016, https://bja.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh186/files/media/document/BJA-2016-9255.pdf, Accessed 18 August 2020

Although PDMPs are implemented at the state level, federal law enforcement such as the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has unfettered access to the prescribing records states collect. States such as Oregon and Utah have challenged this power on Fourth Amendment grounds, but federal courts ruled in favor of the DEA saying state law provides a “positive conflict…so that the two cannot consistently stand together” against Oregon in 2014 and “physicians and patients have no reasonable expectation of privacy from the DEA” against Utah in 2017.9Lisa N. Sacco, et al., “Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs,” CRS Report, www.fas.org, 24 May, 2018, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42593.pdf#page=26, Accessed 8 August 2020

Due to increased access to funding and resources under the Harold Rogers Program, by 2016, every state with the exception of Missouri had enacted some form of a PDMP (see Table 1). States vary on the extent to which types of participation in these databases are mandatory and on what types of drugs are monitored. All states with PDMPs monitor at least Schedule II-IV opioids, and the majority of states also monitor prescriptions for Schedule V opioid products, such as codeine cough syrup. PDMPs are administered by state government agencies and compile accessible information on prescribing histories, which is entered into the database by health care providers. These systems are updated on a daily or weekly basis, depending on the state.“10State PDMP Profiles and Contacts,” Heller School for Social Policy and Management, Brandeis University, www.pdmpassist.org, 2020, https://www.pdmpassist.org/State, Accessed 18 August 2020

The PDMP is now widely regarded as an effective policy mechanism that states can use to combat the opioid crisis. Given the crisis’s wide-reaching effect across the United States, policies such as this aimed at curbing opioid overdoses are now considered a priority by politicians across the political spectrum. Legislators with ideologies as differing as Senators Bernie Sanders (D-VT) and Rob Portman (R-OH) have rallied in unison to support legislation aimed at lowering overdose deaths. In a time of unprecedented political divide and gridlock, it is exceptional for any policy to garner such universal support.

For example, in October of 2018, the U.S. Senate passed the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment (SUPPORT) for Patients and Communities Act—a bill that strengthened state PDMPs by encouraging interstate sharing of data through nationwide databases such as PMPi Hub and RxCheck Hub and mandated PDMP use for all Medicaid providers—by a margin of 98-1 in the Senate, indicating the unified nature of mainstream political thought surrounding this crisis. Though all PDMPs are administered by the states, this legislation enhanced funding for state PDMPs and created a mechanism by which a patient’s prescription history could be accessed across state lines.11Mary Beth Musumeci and Jennifer Tolbert, Federal Legislation to Address the Opioid Crisis: Medicaid Provisions in the SUPPORT Act, Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, www.kff.org, 2018, https://www.kff.org/ medicaid/issue-brief/federal-legislation-to-address-the-opioid-crisis-medicaid-provisions-in-the-support-act/, Accessed 18 August 2020.

The dire magnitude of the opioid crisis has created an imperative for legislators, forcing them to act quickly in order to stem the rising level of overdose deaths. As Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) stated in 2018 while endorsing the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act: “[t]oo many lives have been lost to the opioid crisis….I am proud of Congress’s actions today to take a stand in efforts to save millions from the ravages of drug addiction.”12https://www.cruz.senate.gov/?p=press_release& id=4126, Accessed 18 August 2020.

It is this sense of urgency—legislating in response to tens of thousands of overdose deaths every year—that has created almost universal support for these interventions, with little, if any, public debate or criticism of them. The only abstention in the Senate to the SUPPORT Act was Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT), who originally publicly endorsed congressional intervention at the American Enterprise Institute, but later expressed worry that the bill would be ineffective despite its good intentions:13American Enterprise Institute, “Senator Mike Lee: Interpreting ‘The Numbers Behind the Opioid Crisis’ |

LIVE STREAM,” The Social Capital Project of the Joint Economic Committee, YouTube, 13 March 2018.

There are some very good elements in this opioid response bill, including strengthening U.S. Customs and Border Protection authority to discover and destroy packages containing illegal controlled substances. Unfortunately, the bill also includes dozens of new grant programs with little accountability for how the dollars will be spent and minimal measurement or analysis on their effectiveness. Good intentions are not enough. In the face of a crisis such as this, we cannot afford to waste precious funds on programs which likely won’t work.14Mike Lee, “Press Releases: Sen. Lee Votes Against Unaccountable Opioid Spending,” www.lee.senate.gov.September 2018, https://www.lee.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/2018/9/sen-lee-votes-against-unaccountable-opioid-spending, Accessed 18 August 2020.

This study finds that Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs fail at their major goal to reduce opioid overdoses. Although Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs successfully decrease prescription rates, they also increase the use of black market opioids. Consequently, as Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs cut off users from legal channels of prescribing and force them to switch to more dangerous illicit drugs, this unforeseen substitution to illegally purchased heroin and fentanyl is the principal reason why Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs ultimately lead to more drug overdose deaths.