On Monday, Chicago City Council will discuss Rahm Emanuel’s proposed ordinance to impose new taxes and regulations on the sale of tobacco products. While no doubt well intentioned, it is unlikely that the ordinance will do much to improve the health of the city’s residents. Nor is it likely much to increase revenue for the city. However, it will almost certainly generate an increase in criminal activity, including an escalation of gang violence and related problems. If the Mayor actually cares about the health of the people of Chicago, he would instead eliminate the tax recently imposed on e-cigarettes.

The ordinance contains two main elements. The first is a prohibition on the sale of tobacco to anyone under 21. The second is an increase in taxes on various tobacco products in order to establish “price floors” that ostensibly would make them in-line with the price of a pack of cigarettes, taking into account the relative risk of those products. A press release announcing the proposals quotes Mayor Emanuel asserting that “These reforms introduced today will help today’s youth make healthy choices and refrain from the harmful effects of a tobacco habit.” But raising the age at which people can legally obtain tobacco to 21 doesn’t help young adults make healthy choices at all; it simply remove choices. It disempowers and infantilizes those young adults who comply and it criminalizes those who disobey.

Some young adults, especially those who already smoke, will almost certainly purchase tobacco products elsewhere – such as Hammond, Indiana, which borders Chicago, where it remains legal to sell tobacco to anyone aged 18 and over. But if these young adults return to Chicago with tobacco in their possession, they will become criminals. According to the Ordinance’s revision to section 4-64-200 (b) of Chicago’s municipal code, it will be unlawful for anyone below the age of 21, “to possess any tobacco product … except (i) in the presence of and with the knowledge and the consent of the individual’s parent or legal guardian, while on private property that is not open to the public, or (ii) at the direction of the individual’s employer when required in the performance of the individual’s employment duties.”

So, a 19 year-old soldier on leave at his own home with his wife and child will have to invite his parents over in order to be able to have a cigarette. There’s something not quite right about that.

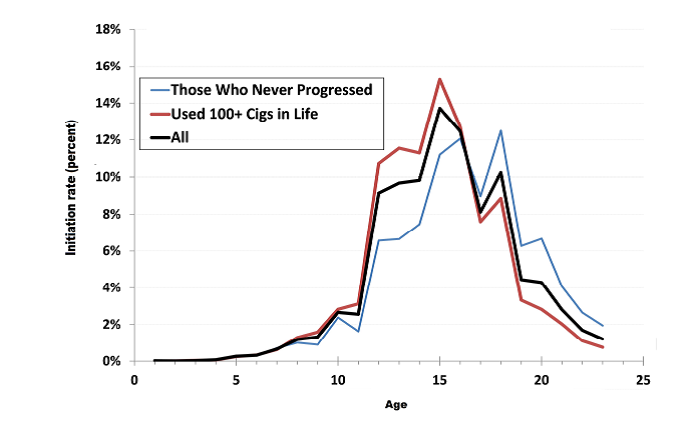

Leaving aside the specious claim that the ordinance will help young adults to make healthier choices; it is unlikely to have a positive impact on health at all. One of the main claims by those who push for raising the age of consent for tobacco to 21 is that it will reduce smoking initiation and thereby prevent the mortality and morbidity that comes from being a smoker. But the main study used to support this contention, undertaken by the Institute of Medicine at the request of the Food and Drug Administration, shows that most smokers aged 26-34 started smoking before they were 18, as this graph from the IOM’s study shows:

Moreover, as the study observes, “Those who ended up smoking more heavily have a distribution of ages of initiation that skews slightly younger, with more initiating at ages 12-16 and fewer initiating after 17. The largest difference is at age 13; 9.7 percent of all smokers initiated at age 13, but 11.6 percent of those who progressed did so.”

Nevertheless, the study concludes that raising the legal minimum age of smoking to 21 would significantly reduce smoking initiation. How can that be, you might ask? The answer is that the study assumes that raising the legal minimum age to 21 will disrupt the supply networks in schools and hence reduce the availability of cigarettes to people aged below 18. If the legal minimum age were raised nationally to 21, such an effect is possible. But in the case of Chicago, 18-year olds will still be able to obtain cigarettes legally in Indiana, so it seems unlikely that the networks of supplies in schools would be much disrupted.

There is another important factor to consider: large scale smuggling. Chicago currently has the highest cigarette prices in the country, mainly due to very high state and local taxes. As a result, there is already a strong incentive for criminal organizations to buy cigarettes in, for example, Indiana or Missouri, where they are much cheaper, smuggle them into the Chicago and sell them illegally. The past few years have seen a dramatic increase in the incidence of such smuggling. By raising the minimum age to 21, Chicago would create further incentives to smuggle cigarettes into the city, thereby exacerbating the problem.

Encouraging the creation or expansion of criminal supply networks may not be an intended effect of Mr Emanuel’s proposal, but it is a near-certain consequence. That is very worrying, because such criminal supply networks tend to be very violent: since all agreements are illegal and cannot be enforced in courts of law, the rule of law is replaced with the rule of man – and enforcement comes in the form of gangs with guns.

Once criminal supply networks are established, it can be extremely difficult to break them. Moreover, as alcohol prohibition the more recent “war on drugs” attest, the attempt to break up such networks often results in an escalation of violence.

The ordinance does attempt to address one perverse element of the current set of taxes on tobacco products, namely the relatively lower rates of tax imposed on loose tobacco. These rates incentivize people to roll their own cigarettes. But an alternative way to eliminate the price differential would be to reduce existing taxes on cigarettes. That would have the beneficial effect of reducing smuggling and the associated costs of criminal activity and enforcement. It could also likely be done in a revenue neutral way.

Another seemingly well-intentioned but ultimately misguided element of the ordinance is its introduction of a higher floor price for smokeless tobacco – to $4.00 per ounce. The ordinance asserts that “This price floor is based on a low-price form of smokeless tobacco, moist snuff, of which a 1.2 ounce can is roughly equivalent to a package of cigarettes, in terms of tobacco quantity. To make the price floor of smokeless tobacco equal to that of combustible tobacco, the floor would be set at $11.50 for a 1.2 ounce can, or $9.58 per ounce. However, smokeless tobacco products carry a significantly lower health risk than combustible products. Thus, a lower price floor is appropriate.”

The ordinance is correct that moist snuff (snus) carries a significantly lower health risk than combustible products. But the proposed floor price implies that snus is about one third as harmful as cigarettes, whereas the evidence suggests that it is far less harmful than that: A 2004 study based on the opinions of experts evaluating the available evidence concluded that snus carried between 5% and 9% of the mortality risks of cigarettes. Meanwhile, a 2007 study found that “There was little difference in health-adjusted life expectancy between smokers who quit all tobacco and smokers who switched to Snus.” That’s right: switching to snus confers almost as much benefit as quitting smoking. Thus, if snus were taxed at a level proportional to the risk it carries, that tax would be far lower than the amount proposed.

At the same time, if the City council is genuinely concerned about the health of young adults, then perhaps it should consider repealing the recently introduced tax on e-cigarettes, which studies suggest pose an even lower risk to health than snus. A report from Public Health England – an agency of the UK government – recently concluded that e-cigarettes are 95% safer than conventional cigarettes. Evidence also suggests that for smokers who aren’t able to quit, e-cigarettes offer an effective and acceptable alternative. Given the potential health benefits that would result from smokers switching to e-cigarettes, it would seem inappropriate to tax the products at all. And the city should end its probably fraudulent campaign against vaping.

The problem for Chicago is not that the good people who live there are addicted to nicotine. It is that the City is addicted to revenue from nicotine products. A recent report suggests that Emanuel wants to use revenue from the increase in tobacco taxes to fund the public school system. But if the taxes really do reduce smoking significantly, this revenue stream will be unsustainable. If the City wants to improve the health of its citizens it would reduce the taxes on all nicotine products, especially those such as snus and e-cigarettes that pose the least risk to health. And it should find other, more sustainable ways to pay for its public schools and other services.