State and local governments take on the bulk of responsibility for taxing residents to fund public education. Due to the fact that local tax revenues are predominantly comprised of property taxes, property-poor school districts across the country often struggle to raise funds for their schools. This is especially detrimental to some of the country’s most economically disadvantaged students who live in these areas.

Although states have adopted a variety of approaches to equalize education funding, such pursuits often fall short of putting students on a level playing field. But one successful education finance reform model for state policymakers to look toward is Vermont’s statewide property tax.

Following the landmark 1997 court case of Brigham v State of Vermont, the state’s legislature passed Act 60, followed by Act 68 in 2003. These reforms radically transformed how Vermont funds its school districts and placed an increased emphasis on a state-based property taxes as opposed to local taxes. Although the education funding reforms were driven by a combination of unique political and economic factors that existed in Vermont at the time, they nonetheless offer a valuable case study for other states pursuing the goal of achieving school finance equity between school districts of varying property wealth.

Background

Vermont’s 1777 state constitution contains an education cause, which requires the state legislature to establish schools in every town in order to educate local children. Because the clause came without detailed guidance on implementation, municipalities were left to work out how to fund, staff and operate schools on their own. This connoted substantial reliance on local property taxes. Even though a state-based property tax aimed at redistributing revenue between more and less affluent towns was enacted in the 1890s, the redistribution mechanism was badly structured and further attempts at reform continued well into the 20th century.

In 1988, the state legislature adopted the “Foundation Aid” formula, which established a minimum-mandated amount of funding for each of Vermont’s pupils and provided state aid to cover the difference between the foundation cost and the tax revenues that each town could raise at a given base tax rate. Similar approaches exist elsewhere, including in Arkansas.

However, problems continued to persist during times of economic crisis like the early 1990s. Since state revenues, such as sales tax receipts, tend to sink during economic downturns, local property taxes were forced to pick up the slack— leading to the same inequities that the 1988 reform was intended to mitigate. State legislators had to grapple with the challenge of devising a new funding reform which could prove resistant to economic downturns.

Brigham v State of Vermont

In 1997, the Vermont Supreme Court ruled that the state’s failure to remedy funding inequities constituted a failure to provide adequate education to some students, thereby violating the Vermont Constitution’s Common Benefits Clause. It’s generally hard to win access to government services as a fundamental right based on such equal protection guarantees, since this would typically force the court to delineate the extent of such service guarantees for each government function. However, the petitioners were successful due to the state constitution’s unique Education Clause that explicitly provides for school education. The verdict provided the final impetus that legislators needed to take action to divorce the connection between local property wealth and education spending, and to promote education finance equity.

Act 60

Act 60, also known as the Equal Education Opportunity Act, was passed by the Vermont legislature within a few months of the Brigham decision. It introduced a two-tier system for local and state funding aimed at separating property wealth and education funding and was implemented over a four-year phase-in period from 1998 onwards. State aid was bolstered through a state-level property tax that applied to both homestead properties, i.e. those occupied by their owners, and non-homestead property. To shield low-income property owners from the impact of the reforms, an income adjustment feature was implemented to lower their property tax liabilities.

The new foundation aid formula for determining the amount of state aid a district is entitled to set a base amount of per-pupil funding, with weights added for every pupil classed as economically disadvantaged, an English language learner, and other groups deemed disadvantaged. There were also varying weights for primary and secondary school students.

Districts were permitted to spend more than the state aid amount, if they voted to finance increases through local property tax revenue and not state funding. Additionally, extra property tax revenue exceeding a certain threshold set by the state is subject to an additional state tax. Essentially, when property-rich districts raise excess dollars, the state mandates some of these funds to be diverted to a “sharing pool” and made available to property-poor districts. The law does ensure that towns planning to spend the same amount would pay the same rate of extra property tax, regardless of their property wealth.

Impact

Within the first year of the reform taking effect, 89 percent of Vermont residents witnessed reductions in their net state and local property tax liabilities. Local property tax bills fell in 32 percent of towns, remained unchanged in 51 percent of towns, and rose in 17 percent of towns.

Despite property tax reductions for some taxpayers, total school funding levels did not drop, in part, because some segments of high-wealth towns were now contributing significantly more than they did previously. When Act 60 was implemented, there were 23 school districts that received less funding than they did previously, partly due to these districts being unable to retain the amount of local tax revenue than they did before. Meanwhile, a whopping 229 school districts received greater funding than they had before Act 60. The education funding reforms were embraced and commended by many towns that benefitted.

However, Act 60 remained controversial and provoked a backlash from some Vermonters. Residents of property-wealthy ski towns disliked the reforms when they experienced sharp spikes in their property tax bills and their local schools could no longer benefit from raising generous per-pupil education funding at low property tax rates. Some districts even witnessed declines in their education funding as they were now forced to share local tax revenues with less property-wealthy school districts. Non-Vermonters with vacation properties in Vermont were also impacted by higher property tax bills, despite having no voting rights on their local or state property tax rates, as were non-wealthy farmers who simply owned many acres of land near wealthy towns. These stakeholders lobbied against the act, filing lawsuits against the state, circumventing the “sharing pool” by creating a separate local fund for raising their desired per-pupil spending amount, or simply by withholding excess local revenue from the state.

Act 68

To address the above concerns, and to dissuade other towns from circumventing the sharing pool through separate local or private funds, Vermont’s legislature passed Act 68 in 2003. The new law increased the per-pupil base spending amount and abolished the education portion of local property taxes entirely, opting for a single, statewide property tax regime.

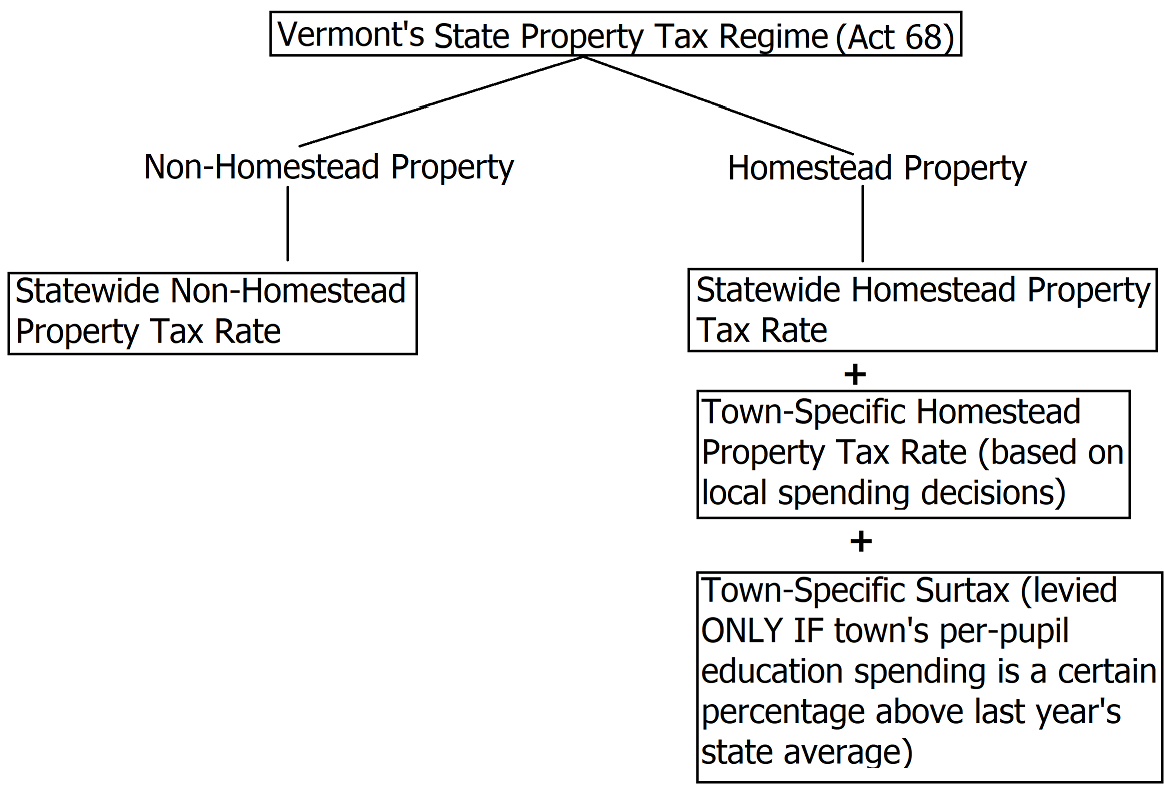

To address the issues faced by non-homestead property owners, including out-of-state vacation property owners, a separate tax rate was implemented statewide, with no connection to local spending decisions in which these owners typically have no vote. For homestead property owners, two rates were implemented. The first was a single statewide property tax rate and the second was a town-specific tax rate that depended upon the amount above the state-specified spending amount which the town votes to spend on education. These changes ensured that spending amounts on education did not vary by local property wealth.

Finally, a surtax was levied on towns spending more than a certain percentage above the previous year’s per-pupil spending average, thereby discouraging property-wealthy towns from approving radically more generous education spending than their less wealthy peers.

By cementing a single, statewide revenue pool for school finance and implementing adjustments to tax rates based on stakeholder concerns, Act 68 built upon Act 60 and succeeded in increasing inter-district funding equity. This has since been confirmed by a review of Vermont’s school finance system which found that the state meets or exceeds benchmark standards for U.S. state funding equity, that per-pupil funding is largely divorced from local property wealth, and that even schools with a high proportion of low-income students can produce significant improvements in learning outcomes over time. The Wall Street Journal reports that in the years following the 2008-09 financial crisis, Vermont bucked the national trend at the time by increasing its per-pupil spending amount despite the recession.

Lessons Learned

Vermont’s successful transition away from local property taxes and to an equitable statewide property tax for school finance offers a number of takeaways for policy-makers considering similar policies for their own jurisdictions. Act 68 successfully addressed the concerns of various stakeholders without abandoning the main principles of inter-district spending equity independent from property-wealth. In addressing these concerns, it compensated for the perceived lack of community consultation preceding the hasty passage of Act 60. The reforms were also made possible by Vermont’s longstanding history and constitutional provision of prioritizing education funding equity at the state policy level.

Importantly, however, a number of factors specific to Vermont were also instrumental to driving reform. In addition to the Vermont Constitution’s unique education clause that drove the impetus for change through the Brigham verdict, the post-1996 Vermont government was also uniquely suited to passing ambitious reform as a single party controlled the House, Senate and governorship. For state governments with divided control between parties, a greater degree of inter-party consultation would be necessary and would ensure that more stakeholders’ concerns are taken into account prior to passing laws that are potentially unpopular in some communities. Additionally, Vermont’s relative demographic racial homogeneity meant that reforms could focus solely on economic equity without the need to consider equity in minority communities, a concern that states with a more heterogeneous population will likely need to address should they pursue similar funding reforms.

It is long past time to address education funding inequity that affects communities across the nation. Policymakers seeking to implement meaningful reforms in this area should look to Vermont’s pursuit of funding equity and see that true progress can be made.