In 1977, prominent Yale scholar Bayless Manning published a law review article titled “Hyperlexis: Our National Disease,” in which he assailed the alarming profusion of “new statutes, regulations, and ordinances,” many conferring criminal penalties, that were “increasing at geometric rates at all levels of government.”

Unfortunately, the decades since Manning’s prediction saw a further explosion of criminal overreach, pulling more and more people and types of conduct into the system to the point where today, one in three adult Americans has a criminal record, and U.S. incarceration rates dwarf those in most of the world. Even worse, more than one-third of people in prisons have a diagnosed mental illness, and an even larger share reports mental health concerns. And people with substance use disorders are overrepresented in the prison populations, to the tune of 49% in state prisons and 32% in federal ones.

When we arrest people who are struggling with their mental health or substance use disorder, we are not properly carrying out any valid criminal law function. We have decades of research that shows us that arresting and imprisoning people does not address the root problems they are facing, and yet that is what our churning system does, decade after decade, with few intervening to apply common sense.

Some people must be dealt with in the criminal legal system to keep us all safe and uphold the rule of law. But for too long punitive measures have been administered to huge populations categorically not suitable for criminal sanctions and interventions. Addressing the expensive, unwieldy, and ineffective overapplication of criminal legal sanctions is the way to meet the moment.

The drug war ramps up criminal sentences

Despite the already bloated criminal codes Manning decried in 1977, the 1980s and 1990s saw a juggernaut of prison-building (and prison-filling), with added fuel in the form of ever more criminal laws and amped-up penalties. These muscular, weaponized laws included “three strikes” laws (life sentences for repeat offenders, often for minor offenses), enhanced penalties, and mandatory minimums. Between 1990 and 1995, every state except Maine increased their prison populations, some by as much as 130 percent.

During this same period, the federal government used funding streams to reinforce incentives to arrest and imprison more people—such as providing funding for arrests and prison building and offering incentive grants to states that require people to stay behind bars longer. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, for example, dedicated more than $1 billion to “increased funding for law enforcement and mandated harsher penalties in federal drug cases, including life imprisonment.” It is relatively easy to pass criminal laws when people believe they deter crime because public safety arguments—usually propounded by law enforcement officials—are remarkably persuasive.

At the time these heavy-handed policies were ascendant in the ’80s and ’90s, the culture was increasingly accepting of the notion that there are people who are irredeemable—meaning there is little point in attempting rehabilitation. It turns out that we have strong evidence that people who receive education, support, training, and mental health and substance abuse treatment (not to mention stable housing) can, in many cases, stay successful and be productive in the community without committing crimes.

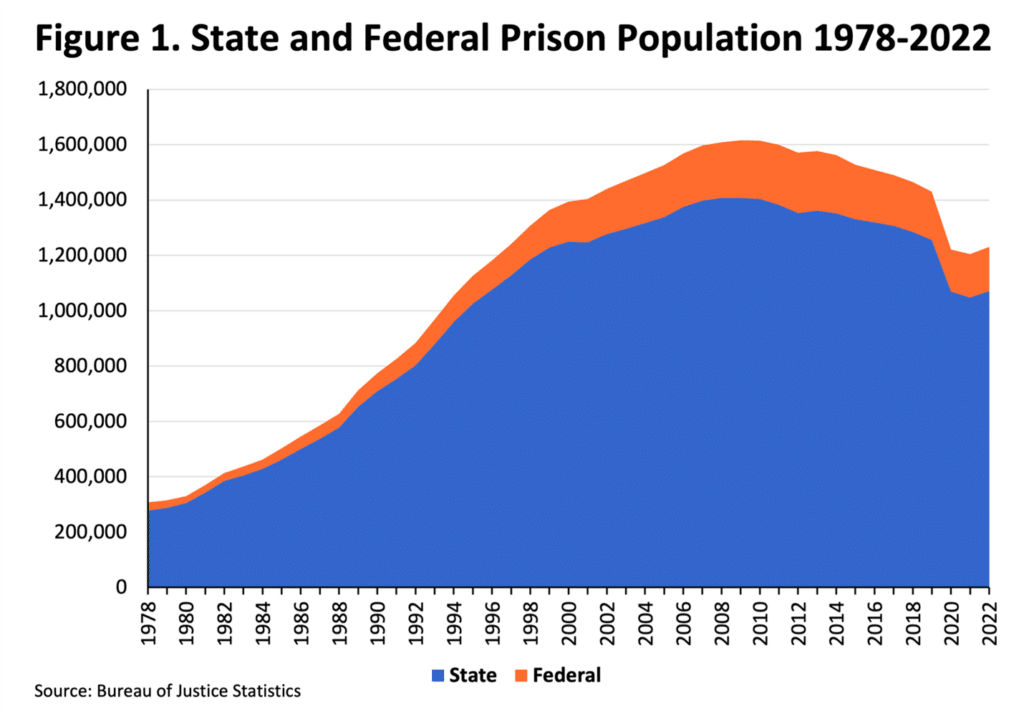

In 1980, 315,974 people were held in U.S. prisons (state and federal). By 2021, that number had ballooned to 1.2 million. From 1973 through 2009, the prison population multiplied by seven. These figures do not include federal and state jails, which hold mostly pretrial populations and people serving short sentences—these had reached 636,000 in 2021. And in 2021, there were almost four million additional people on probation or parole. From another perspective, in 2024, we incarcerate 583 per 100,000 people in the U.S., more per capita than any other country, when in the 1970s, we were about in line with many other countries. In 1980, the U.S. incarcerated just 139 people per 100,000.

By the high point in the prison boom, we had spent trillions incarcerating people for decades and mushroomed the number of people we put behind bars, earning us the distinction of being the world’s highest incarcerator. The War on Drugs was fully underway, and a heavy focus was placed on crack cocaine. Lawmakers glommed onto a myth of “superpredators” as if crack conferred some kind of enhanced capabilities to that era’s lawbreakers.

During the same timeframe, homelessness emerged as a problem, partly as a consequence of the emptying of mental hospitals that had warehoused an alarmingly large number of people (in the range of half a million at one point). As NPR explains, “In the mid-to-late 20th century, America closed most of the country’s mental hospitals. The policy has come to be known as deinstitutionalization. Today, it’s increasingly blamed for the tragedy that thousands of mentally ill people sleep on our city streets. Wherever you may stand in that debate, the reform began with good intentions and arguably could have gone much differently with more funding.”

This story of a policy change being launched with good intentions only to fail to follow through with the investments needed to make the policy successful is echoed in other experiences in our country’s history. The same narrative is true for many who enter our criminal justice system: If the right investments had been made in their success earlier in their lives, they would probably have never gotten to the crisis level that led them to commit crimes. In our short history as a nation, we have too often failed to follow through on investments of money and effort that were foreseen as necessary to truly address a problem.

For example, in housing policy, following the profusion of criminal penalties, lawmakers failed to provide ways for people—already disrupted by incarceration and the loss of income, debt from fines and fees, and other economic hits—to access safe places to live and services, such as job training and treatment for substance use, when needed. People were set up to fail, and many ended up incarcerated again.

These continuing policy failures that have morphed into long-term intractable problems come across as a lot of déjà vu to anyone who has been watching this space for decades. In order to reverse overcriminalization safely, it is necessary to decriminalize and invest in care infrastructure and build economic opportunity in communities that have been heavily overpoliced. But an essential part of the policy prescription—the reinvestment piece—was never implemented.

The long-term project of facilitating better lives for individuals and the community has to include eliminating the unnecessary, costly, and counterproductive use of prison and jail as reflexive responses to public instability. A recent five-year randomized controlled study found that supportive housing “effectively ended chronic homelessness for participants and lowered the public cost of the homelessness-jail cycle.”

Based on recent scholarship, it is a matter of criminological fact that incarceration is not conducive to reducing future crime. So we must be especially critical of the use of public spending for incarceration when compared to other forms of public spending that are tailored and responsive to the problems driving much incarceration, such as poverty and lack of opportunity, untreated mental health conditions, substance use issues, and traumas.

The increase in incarceration in the slipstream of deinstitutionalization was perhaps inevitable, as it coincided with a shift in the system’s focus from rehabilitation to punitive incarceration, and “‘dangerousness’ became the category of primary importance and the key determinant of incarceration.” During this time, the question of whether to employ incarceration did not change, merely the explanation for the incarceration.

A similar view was baked into the federal Sentencing Guidelines, which, when they were adopted in 1987, were structured so as to ensure that incarceration would be the default approach to all sentencing. The enshrinement in the guidelines all but cemented our path to mass incarceration, as federal practices often serve as models for states (though some states and localities have initiated innovative practices that are leading the way toward more scalable solutions).

Reform is needed, or in another 50 years we will still be in the same situation we are now (and were back in the days of the original Hyperlexis). Manning’s warning failed to prevent a shift toward incarceration as the default way to respond to societal problems. At this point, there is general agreement across the aisles as to the overarching wrongness of overcriminalization and even some of the remedies. As Brett Tolman, Executive Director of Right on Crime, testified: “Overcriminalization offends both sides of the aisle.”

The consequences of overcriminalization

Failing to correct for the overreach of our system is causing grave harm. Evidence is pointing away from the punitive criminalization approach: After all, if tough on crime were a winning strategy, we wouldn’t have high rates of recidivism (people getting in criminal legal trouble again after serving their sentences) and wouldn’t still be spending ever-larger portions of budgets at every level of government on crime enforcement and punishment.

In fact, our record on recidivism is dismal—a DOJ study found that “82 percent of individuals released from state prisons were rearrested at least once during the 10 years following release. Within one year of release, 43 percent of formerly incarcerated people were rearrested.” And our spending is way out of line with the rest of the world’s. “A comparative overview of government expenditures on prisons across 54 countries shows that penitentiary budgets usually amount to less than 0.3 percent of their gross domestic product (GDP),” according to Penal Reform International. The United States spends about three times that amount of our GDP each year on incarceration, estimated at more than $182 billion annually.

Overcriminalization also undermines the legitimacy of our system. According to Patrick Purtill, director of legislative affairs for the Faith & Freedom Coalition, the current system “tilts the playing field too far in favor of the prosecutor. … Ninety-eight percent of cases in federal court end with a plea, and there is substantial evidence that innocent people are coerced.” Purtill further points to overcharging as a problem because there are so many options for prosecutors, whose success on the job is typically evaluated based on how many convictions they obtain.

Purtill added that originally criminal laws were only passed to hold people accountable for “inherently blameworthy crimes” like murder or assault or taking other people’s property, but the proliferation of laws in the tough-on-crime era has criminalized so many forms of conduct that there is no longer a meaningful correlation between breaking laws and being a blameworthy person or a scofflaw. We should not want a complicated criminal code or one that ensnares a large portion of our population. We should aim for something quite easy to understand and follow, and that doesn’t criminalize common behavior.

Overcriminalization also hurts our ability to effectively address violent crime by criminalizing non-violent and even non-blameworthy behaviors. Consider how drug arrests—because they almost always involve a suspect in custody—require fast processing of the confiscated contraband. Accordingly, when drugs are brought to crime labs, they often jump the line over unsolved murders and untested rape kits. This contributes to slower investigations and lower solve rates of violent crimes. For example, in the mid-1960s, more than 90% of murders were solved. By 1990, that percentage fell into the 60-percent range.

Solve rates have continued to decline. By 2020 the national clearance rate dropped to about 50 percent for the first time ever. There is good reason to attribute some of our failures to solve murders and other violent crimes to the dilution of purpose that the last 50 years have wrought in our criminal law.

Another downside of excessive criminalization is that it creates huge bureaucracies, is expensive to run, and gums up the works of the economy. The “buildup of crimes slows economic growth,” says Patrick McLaughlin, senior research fellow and director of policy analytics at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. One study pegs spending incarcerating people in the US at 6% of GDP and estimates that for every dollar spent on incarceration, we generate $10 in social costs. Scholars have estimated that mass incarceration has increased poverty nationwide by 20 percent.

What to do

Given the length of time we have been grappling with this problem, we know about fairly sophisticated ways to address it. In the ’70s and ’80s, we didn’t know a lot of things we do now, like how brain development impacts crime and the harms of incarceration. Now, we have a wealth of data over decades that tells us what works and doesn’t work to hold people accountable. This entails taking the many people whose conduct can be safely addressed without imposing incarceration and instead providing rehabilitative programming, treatment, job, and housing support, and other interventions that respond to the criminogenic needs of the individual in the community. Such a response allows them to maintain stability in housing, jobs, childcare, and other parts of life that would be interrupted by prosecution.

But instead, we keep ratcheting up the punishment side without following through on prevention and addressing root causes. Incarceration sentences are imposed in the vast majority of cases for which incarceration is an option under the law. Only a sparse and largely siloed fraction of federal and state jurisdictions formally pursue any alternatives to incarceration—in fact, in 2023, 92.4 percent of all federal cases that ended in a sentence included an incarceration term as part of that sentence. The judges and prosecutors that regularly dispense non-carceral sanctions uniformly report that these programs are suitable for much larger swaths of people currently being consigned to confinement. Somehow prison went from being an option to being the presumption. We need to go back to first principles and get clear about how to realize our vision.

Reversing the presumptive resort to the punishment and incarceration model will mean interrogating even the things we have done for a long time reflexively. For example, not everyone whose conduct leads to incarceration today needs any punishment at all, let alone a prison sentence.

There are numerous ways to strip down our system to the essentials. Some low-hanging fruit, of course, is to get rid of conflicting and silly relic laws that have stayed on our books—laws along the lines of writing checks for less than $1 or owning a ferret. Criminal laws are not the kinds of things you want to be littered around and not being used. They are blunt, heavy-handed instruments.

But to make a difference, it will be necessary to wrestle with the extent of criminalization of behavior that is not inherently harmful, like drug possession, sex work, or (in some jurisdictions) camping in a public place such as a park. A law prohibiting that conduct in Grants Pass, Oregon, was just upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court, even where people were homeless without available shelter space.

Another example of overuse of the system for non-criminal conduct is the huge number—fully one-quarter of prison admissions nationwide—of people held in our prisons and jails for non-criminal, “technical” violations of parole or probation.

For people sentenced to prison, there should be a process for reviewing all criminal cases after a set number of years (or a percentage of the sentence), letting a new judge reassess the sentence in light of present circumstances, including rehabilitation post-sentencing. These so-called “second look” laws are proliferating at the state level as a way to clear prisons of longtime residents whose continued incarceration serves no valid objective, instead costing states hundreds of thousands of dollars and extending unnecessary family separations.

Another helpful tool would be to provide for a periodic automatic “sunset” review for at least a subset of criminal laws. This, of course, would not solve the problem alone but would attune legislators to the idea that these laws should only be retained if they are working as intended to address penological functions like deterrence, rehabilitation, and protecting the public.

Instead of criminalizing poverty and applying the crudest and most costly tool we have at our disposal, a demonstrably better approach would create rehabilitative and restorative and preventative spaces, such as supportive housing; boosts in educational opportunity and attainment; and guarantees of access to mental health/substance abuse treatment to all seeking it, as well as health care, so communities can address many problems before they can lead to criminal system involvement.

A libertarian view on crime and punishment argues that “[T]he proper role of government is limited to restraining the use of force and fraud in the conduct of human affairs, thus preserving the maximum scope for freedom of action for all persons governed by the legal order.” This view has been roundly rejected by the United States, as can be seen by the prevalence of carceral responses that emerged during the mid-twentieth century.

Nevertheless, the case for parsimony in our use of criminalization, incarceration, and even punishment itself, is gaining ground in the most thoughtful criminal law policy circles. In the seminal 2023 book, Parsimony and Other Radical Ideas About Justice, editors Jeremy Travis and Bruce Western define parsimony as the principle “that the state is entitled to deprive its citizens of liberty only when that deprivation is reasonably necessary to serve a legitimate social purpose.”

We should fully oust (at least some) non-violent crimes from the criminal pantheon; most notably, all drug possession laws. The logical endpoint has to be shifting away from responding to disruptions in public safety and toward treating public health problems and “crimes” that stem from economic desperation.

The unrealistic expectation of eliminating all crime

The drastic response to crime in the ’80s and ‘90s ushered in a politics in which both major political parties supported amped-up penalties and endless addition of criminal sanctions to broad categories of behavior. In such an environment, it becomes difficult to initiate reform unless that reform could virtually eliminate crime. While that viewpoint thawed measurably beginning in the early years of this century, the past five years have seen a political regression back toward this stance. In recent years, criminal legal reforms, especially pretrial reforms, have been blamed for almost every violent crime in major cities, even when the data squarely refute that connection and cities that did not undertake these reforms saw similar jumps in crimes.

Even today, many legislators worry about blowback if they support any reductions in the use of punitive incarceration, and this skews policymaking toward overcriminalization and over-incarceration. If we have a chance to move the conversation to robust solutions, we need to collectively free lawmakers from the prison of that hackneyed “tough-on-crime” model.

Policymakers across the political spectrum today would agree that some penalties adopted in the prison-building decades went further than was needed to serve valid public goals and that there is no logic nor utility to imprisoning people for life for nonviolent crimes such as possessing small amounts of drugs for personal use. That said, it is a chilly climate for even modest reforms in most legislatures—indeed, many jurisdictions have been rolling back reforms and ratcheting up penalties again with barely revamped and warmed-over rhetoric from the superpredator era. Policymakers across the political spectrum contributed to this oversized monster of overcriminalization, and it will likely take bipartisan efforts to curb its excesses.

Even as lawmakers dismiss the solutions, people in American communities understand that incarceration is not always the best approach and that we are criminalizing more people and incarcerating them for longer than was ever intended. In 2022, 75% of victims of violent crime said they would prefer non-carceral treatment or restorative justice to prison. In another more recent poll of all likely voters, 78 percent support criminal justice reform, remaining roughly flat from 2022. According to another study, 77% of American adults believe that alternatives to incarceration are the most appropriate sentence for non-serious offenses, as opposed to prison or jail. And in a 2024 poll, six in 10 respondents said they would not penalize—and would instead be more likely to vote for—politicians who supported reform.

In rolling back the excesses of the current system, our biggest danger is the baseless fears promulgated by entrenched law enforcement and other officials opposed to reform. And politicians are loathe to step in based on those same stoked fears.

Can we find a way to let go of our fears and embrace the overcriminalization discussion that is truly, monumentally before us? If not, we will continue to give up on larger and larger percentages of our people, removing them from society and the opportunities to productively reenter that society later. In other words, when it comes to making our criminal justice system better, we have nothing to fear but fear itself.