In July 2022, the six New England state governors sent a letter to U.S. Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm raising concerns that the region’s energy costs would spike this winter due to a lack of liquefied natural gas (LNG), which the area has limited access to thanks to the Jones Act. This century-old, protectionist law restricts all domestic shipping to U.S.-flagged, -built, -owned, and -staffed vessels, excluding oftentimes cheaper international competitors from U.S. maritime trade.

Liquefied natural gas costs have gotten so high that it has become cheaper for New England states to import LNG from overseas than from the Gulf Coast, which produces natural gas in abundance. For example, according to a 2011 Department of Transportation Study, a Jones Act-compliant ship costs around $20,000 a day to operate, while a foreign-flagged ship only costs $7,400 per day to operate.

While pipeline permitting issues are largely to blame for New England’s limited supply of natural gas, the Jones Act compounds this problem by raising costs and limiting access to the next-best alternative.

Normally, the Jones Act hurts island states and territories, such as Hawaii, Alaska, and Puerto Rico, far more than states that are a part of the mainland U.S., but New England is unique when it comes to its energy grid. With limited pipeline capacity, New England finds itself at the mercy of maritime shippers when demand spikes for energy.

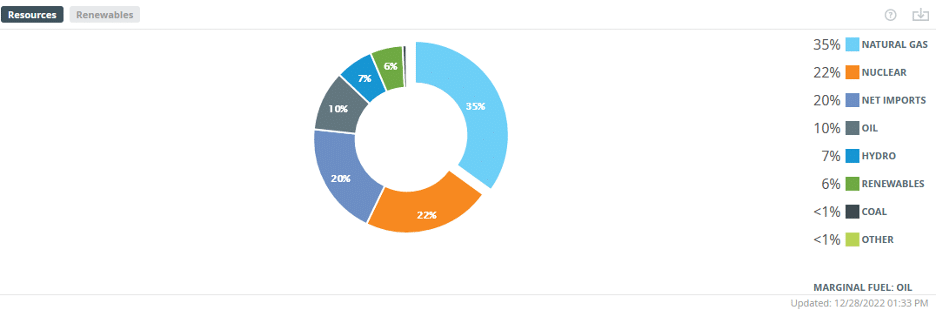

Figure 1: New England Energy Grid Resource Mix

With 35% of the New England energy grid reliant on natural gas, the region has been left out in the cold for an antiquated, protectionist law. The Jones Act is currently protecting a domestic maritime industry that does not exist. The U.S. Jones Act-compliant fleet currently has zero LNG tankers, making it impossible to meet demand with domestic capacity.

The reason for the total absence of a Jones Act-compliant liquefied natural gas tanker fleet is unfavorable economics. A Government Accountability Office report in 2015 found that U.S. carriers would cost about “two to three times as much as similar carriers built in Korean shipyards and would be more expensive to operate,” and costs associated with transport would be higher. Instead of relying on other nations’ comparative advantages in shipbuilding, the United States has effectively isolated itself from international competition in a market in which it makes no effort to compete.

Historically, when the Jones Act hinders U.S. responsiveness to crises, as it often does, temporary waivers have been the answer. For example, U.S. Sens. Angus King (I-ME) and Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH) said they were working on legislation that would “authorize the President to issue a limited, short-term Jones Act waiver,” but Jones Act waivers have become even more difficult by recent congressional actions.

In recent years, Congress has used the annual reauthorizations of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) to narrow Jones Act waiver eligibility. In the 2021 fiscal year NDAA, Section 3502 changed the Jones Act’s waiver requirements so that waivers can no longer be issued “broadly” and now must be related to an “adverse effect on military operations.”

This year, the domestic maritime industry received another Christmas gift buried deep within the 2023 NDAA: more Jones Act waiver restrictions. Under the latest National Defense Authorization Act, Jones Act waivers can be granted no earlier than 48 hours after the waiver request has been published online. It also imposed new restrictions on ships already carrying cargo, effectively requiring them to unload, apply for a waiver, wait at least 48 hours, and then be on their way.

For a law made to shore up domestic U.S. capacity in case of emergencies, the Jones Act has seemingly made matters worse. Considering the frequency with which it needs to be waived, Congress should reconsider whether the Jones Act should be a law. From being waived by President Franklin D. Roosevelt five days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 to being waived by President Donald Trump after Hurricane Maria in 2017 to President Joe Biden’s far more restrictive individual waivers following Hurricane Fiona, and the many times it was waived in between, the Jones Act has served as a hindrance, even on the grounds by which it was originally rationalized.

Repealing the Jones Act is the best solution to bolstering energy-insecure New England’s grid during crises in lieu of pipeline infrastructure. But short of outright repeal, smaller steps could be taken to lessen the negative impact of the Jones Act in times of emergency.

As Cato Institute’s Scott Lincicome and Colin Grabow wrote in RealClearPolicy, these steps would include streamlining the waiver process, undoing the waiver restrictions made by the 2021 and 2023 National Defense Authorization Acts, and granting automatic waivers for any region subject to a national emergency declaration.

Given the Jones Act’s track record for exacerbating disasters rather than mitigating them, it is in the national interest to lessen its impact on maritime commerce.