As the U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C., considers USA vs. Google, a federal anti-trust lawsuit to determine whether Google’s status as the default search engine on Android and Apple devices is illegally anti-competitive, there may be emerging evidence that could help settle the case in Google’s favor.

The federal anti-trust case revolves around the contracts that Google negotiates with Apple and Android device manufacturers. These contracts make Google the default search engine ‘out of the box’ when users first turn on a new device they’ve purchased. The government argues these contracts lock in Google as the market leader, prevent competition, and limit user choice.

In 2018, during a similar inquiry into Google’s default status, the European Union ordered Google to offer a ‘choice screen’ where users could choose which search engine they wanted as their default when they first booted up their devices. The theory was the same one argued in the USA vs. Google case, namely that Google’s automatic default status on Android devices and Apple’s safari secured Google’s dominant position by insulating them from competition. The Department of Justice argues that by occupying the default position, Google forgoes competition because the default settings are so “powerful” in persuading users which option to choose. Google countered that they occupy the largest market share because they offer the best product and that providers, like Android and Apple, and most browser users choose Google over other options when given the choice.

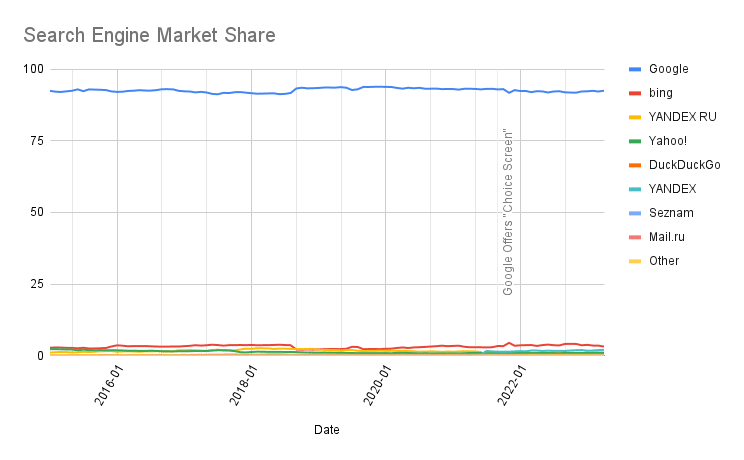

If the European Union’s theory is correct, and users are funneled into using Google, one would expect relative search engine market shares to change after users are offered a choice screen. Google began offering users the choice screen roughly around Sept. 2021, and search engine market share data is available through March 2023, approximately 18 months for the theorized impact.

While there is no settled methodology for determining causality in this situation, it seems reasonable to expect that some users would have changed search engines after 18 months of having the option, presenting a reasonably well-preserved natural experiment.

However, the European data show that search engine market shares remain unaffected by the choice screen. Google has maintained a roughly 92% market share in Europe before and after the European Union mandated the choice screen in Europe.

The month after the choice screen was implemented, Bing increased its European market share from 3.34% to 4.48%, only to return to 3.46% the following month. Users switched to Bing when offered the choice screen but quickly reverted to Google after less than a month. This suggests that users choose between options but that Google is the overwhelming favorite when they choose.

A fundamental flaw in the Justice Department’s argument is that even without a startup choice screen, U.S. consumers can still change their default search engine at any time they choose, sometimes in as few as four clicks. The claim that default status “locks in” Google is a theoretical argument based on psychological research. The European Union’s choice screen hasn’t significantly increased market shares for other search engines because users can change their default search engine after starting up their devices. Most users appear to choose Google over other search engines.