Nebraska’s municipalities are somewhat of an outlier nationally as most cities and counties across the state offer either a cash balance plan or defined contribution plan to public sector workers. Two striking exceptions to this are the cities of Omaha and Lincoln, each of which offers defined benefit retirement plans for public safety workers. Omaha runs a defined benefit plan for its civilian employees too (though new hires for the next few years are being offered a cash balance plan as a part of a collective bargaining agreement). Unfortunately, Omaha and Lincoln are not exceptions when it comes to the accumulation of unfunded pension liabilities.

As of last year, Omaha is reporting a combined $835 million in unfunded liabilities and 50% funded ratio for its Police and Fire Retirement System (PFRS) and Employees’ Retirement System (ERS). Lincoln meanwhile reports its Police and Fire Pension Fund (PFPF) is 71% funded with $82 million in unfunded liabilities.

Unfortunately, these numbers — as bad as they are for city governments — don’t accurately state the full depth of the problems for the two largest Nebraskan cities. Omaha’s unfunded liabilities are likely more accurately valued at $2 billion with a 29% funded ratio, while Lincoln is facing unfunded liabilities closer to $190 million making it just 52% funded.

These are just the initial findings from two separate policy studies co-authored with my colleagues Truong Bui and Daniel Takash, one each for Omaha and Lincoln on their individual, but related challenges.

- Read the City of Omaha pension debt report here.

- Read the City of Lincoln pension debt report here.

Both cities have faced similar challenges with underperforming investment returns.

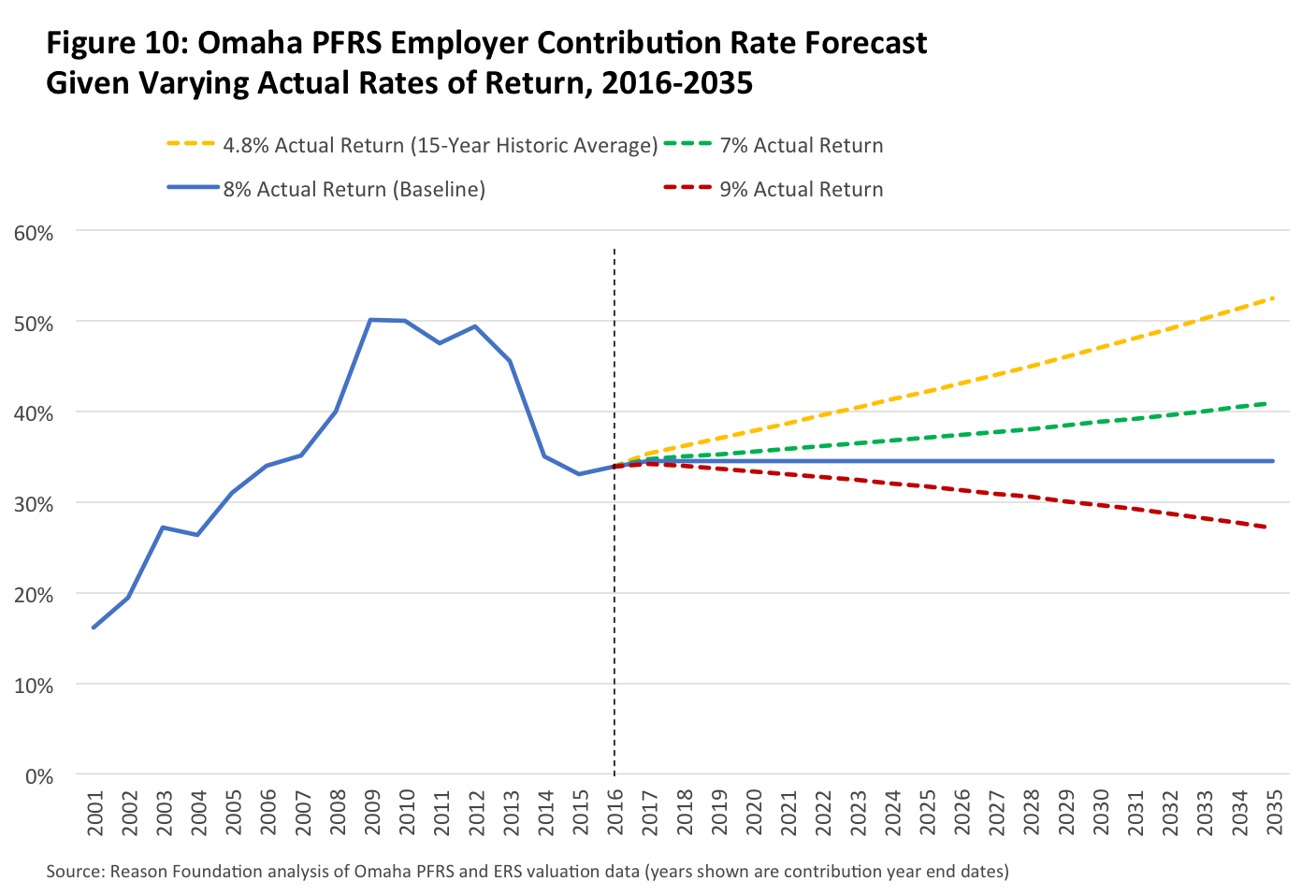

Omaha PFRS and Omaha ERS have long assumed 8% rates of return. However, the 10-year and 15-year average returns for each plan’s investments have only been between 4.5% and 4.8%. Even going back 20-years (which starts to reflect asset portfolio allocation that isn’t particularly relevant to forecasting future returns on today’s allocation) Omaha ERS only has averaged a 6% return.

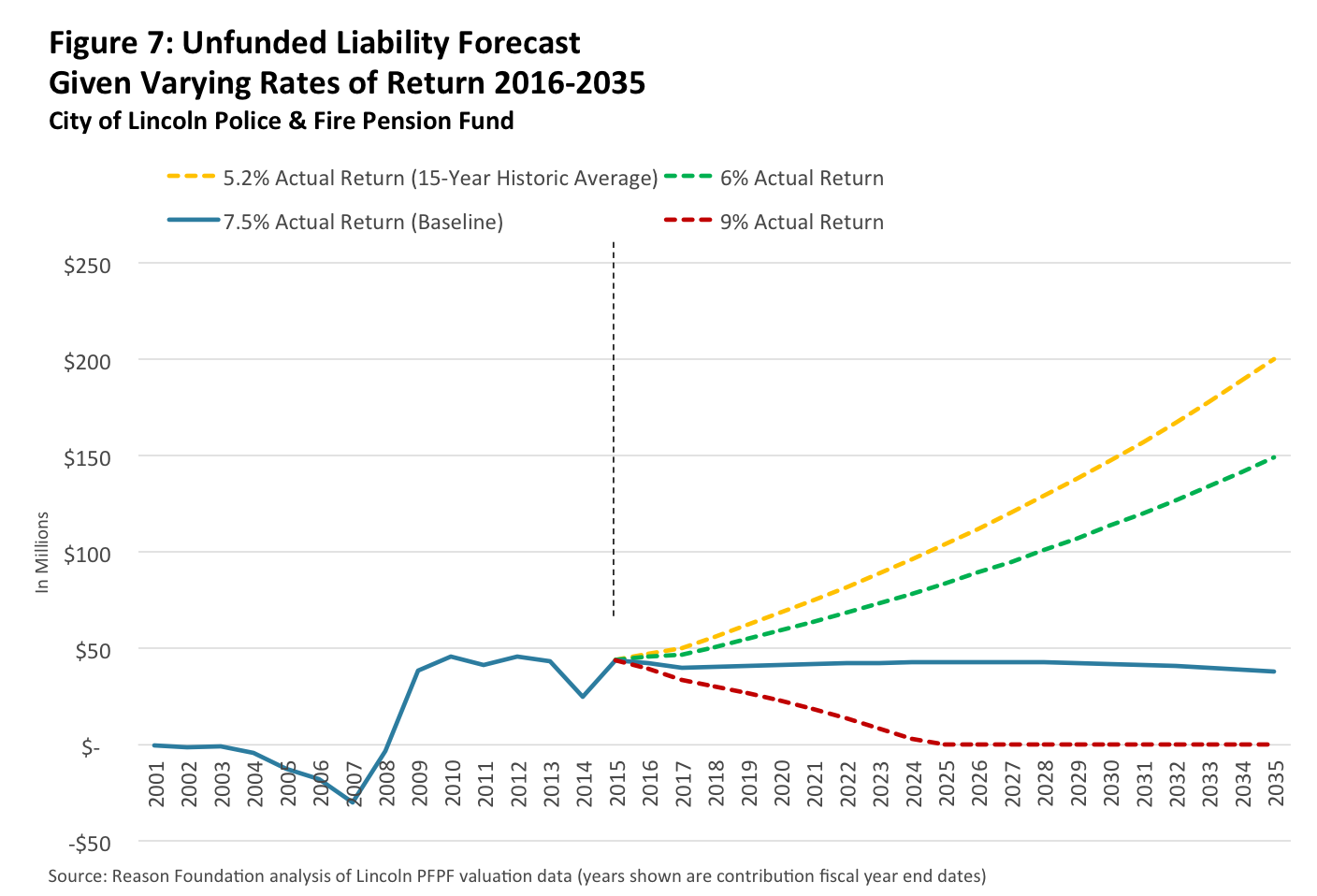

Lincoln PFPF similarly has underperformed with a 4.1% 10-year average and 5.2% 15-year average compared to assumed returns that have ranged from 6.4% to 7.5% over the past few decades.

These missed investment returns are the largest driver of unfunded liabilities, but not the only cause. Neither city has consistently paid 100% of the actuarially determined contribution rate. And even if they had, the discount rates being used to value accrued liabilities — and thus calculate unfunded liabilities and amortization payment rates — have been undervaluing those promised pensions consistently since the mid-2000s. The actuarially determined employer contribution rate is thus tacitly underfunding the city plans too.

A more unique problem for Lincoln has been the funding process for the city’s 13th Check, plus a misguided decision last fall to increase the assumed return back up to 7.5% after it had fallen to 6.4%. In Omaha, labor agreements going back to 2010 have attempted to solve problems with the city’s public safety plan, but benefit cuts and increased employer contributions haven’t meaningfully addressed the underlying challenges causing the unfunded liabilities in the first place.

Even the recent decision to create a cash balance plan for Omaha ERS is a few steps short of complete reform for the civilian employee plan because the cash balance plan could be reversed by a future collective bargaining agreement and the existing defined benefit plan is still assuming an unrealistic rate of return.

Our reports on Omaha and Lincoln, which are co-published with the Nebraska-based Platte-Institute, show in actuarial forecasts what the cities can expect to see in the coming years without meaningful changes to funding policy and plan design for new hires.

For example, if the investment performance trend in Lincoln continues, the public safety retirement fund’s unfunded liability is likely to quadruple over the next 20-year. (See the nearby Figure 7 from the Lincoln pension report.) Of course, this forecast uses the city’s discount rate to value liabilities — meaning the actual growth in unfunded liabilities is likely to be an even higher dollar amount.

Omaha’s public safety plan meanwhile should expect to see the city’s contribution rate grow from around 33% of payroll to more than 52% of payroll over the next two decades if their investment return continues along historic trends without any changes to assumptions. (See the nearby Figure 10 from the Omaha pension report.)

To see the details behind these analyses, as well as a detailed set of policy proposals to fix the existing defined benefit plans and create better retirement plans for future employees, see the full papers and check out Platte Institute’s coverage as well.