As the Mississippi River’s water level drops to unnavigable levels for the second time in two years, lawmakers must look for cost-effective ways to make the river navigable.

As it stands, aside from diverting all of the water from spillways to the Mississippi River, the only means of keeping the river navigable by commercial barges is constant dredging, which removes sediments and debris from the bottom of the river to increase the depth and ensure the safe passage of boats.

In the United States, dredging is artificially expensive thanks, in part, to the industry being insulated from foreign competition by the Foreign Dredge Act of 1906, and federal lawmakers ought to reexamine if this law is worth retaining.

In late 2022, the Mississippi River reached a record low of 10.81 feet below base level. This low level, resulting from a multi-year drought, led to emergency dredging to ensure that the water level was sufficient to accommodate commercial barge traffic. During that crisis, experts warned that the extreme drought and flood cycle would occur again.

Now, those experts are being proven right. The depths of parts of the Mississippi River are once again dropping to critical levels. Barge flotillas are being reduced in length and width to avoid running aground on the narrowing channels of the Mississippi. The biggest problem is near Memphis, Tenn., as shown in Figure 1 below.

The graph shows the “stage” of the Mississippi River. A river’s stage is determined based on historical factors from the United States Geological Survey, effectively showing a historic water level for a river. A negative stage means the river itself is lower than historical data suggests it should be. With the water 10 feet below stage, the risk of grounding will continue to increase as the water level decreases.

Figure 1: Water Level in Memphis, Tennessee

Source: “Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service,” National Weather Service, Sept. 2023.

Water level projections are at a dangerous threshold, and National Weather Service projections show no reason for optimism. The levels near Memphis are projected to remain 10.6 feet below base level until Oct. 9, when levels are projected to recover slowly.

The U.S. inland waterways system, especially the Mississippi, is critical for agricultural exports, particularly grain, which has experienced market shocks since Russia invaded Ukraine and the Russian blockade of Ukrainian seaborne grain exports.

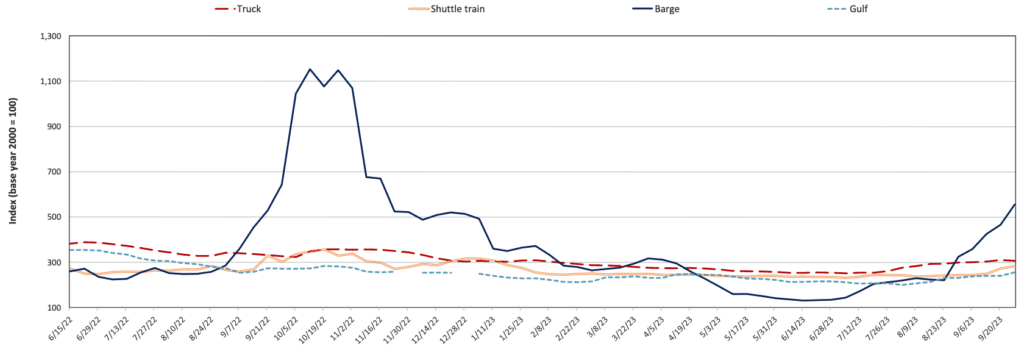

In the wake of this market disruption, U.S. exports have become more essential than ever. Barges are typically the most efficient means of moving masses of grain, with one hopper barge carrying as many as 16 rail cars or 70 truckloads. Any negative impact on barge shipping can have a massive effect on the price of moving grain, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Grain Price Indicator for Different Modes

Source: “Grain Transportation Report,” Agricultural Marketing Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Sept. 28, 2023.

In mid-Feb. 2023, as the previous drought eased and water levels returned to their base level, grain prices declined to normal levels for barge shipping. With the latest drought, grain prices are rising again.

The good news is that much of the winter’s wheat harvest is already completed (as harvest season ends in August). However, many other grains, like soybeans and corn, are harvested in September and October. Increased demand for shipping plus a bottleneck in the Mississippi River in Memphis could jeopardize the cost efficiency of U.S. grain exports for the season.

As for potential solutions? Simply hoping for rain is unlikely to solve the problem. A better option would be enhanced dredging. The United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) spent much of the 2022 crisis months dredging the riverbed of the Mississippi. Typically, USACE keeps one dredger at work 24/7 throughout a dredging season. Starting in Sept. 2022 and ending in Feb. 2023, 2022’s low levels required two-to-three dredgers in constant operation in the St. Louis District, bringing additional dredgers in from other districts.

Based on estimates by Lou Dell’Orco, chief of operations and readiness at USACE’s St. Louis District, the price of keeping three dredgers in constant operation was “$10 million a month.”

If, as experts warn, droughts and floods become more common, policymakers should look for ways to lower the cost of sustained dredging and increase U.S. dredging capacity to respond to these crises.

One of the laws that make both goals difficult is the Foreign Dredge Act of 1906. This law bans foreign dredgers from U.S. waters, functioning similarly to the Jones Act’s shipping restrictions. While European dredgers and dredge fleets have gotten bigger and better, the U.S. continues to rely on a smaller, older fleet of U.S.-flagged, -built, and -crewed vessels, isolating U.S. dredging firms from cheaper international competitors.

A Tulane Institute for Water Resources study found that “the combined capacity of the U.S. [hopper dredge] fleet is less than a single EU [European Union] dredging vessel.”

This insulated dredging market increases costs in the United States. Per USACE data, in fiscal year 2005, 255 million cubic yards of material were dredged by both the Army Corps and domestic dredging firms at a total cost of $957 million. In fiscal year 2022, only 233 million cubic yards of material were moved at a total cost of $1.864 billion. This near-doubling of costs to taxpayers isn’t due to the costs of additional work. In 2005, new dredging work totaled $328 million, and in 2022 new work rose only to $391 million. The cost of maintenance dredging, however, has more than doubled over the last 17 years.

As Colin Grabow, a research fellow at the Cato Institute, wrote, “A coastal restoration project at Whiskey Island, La., cost $118 million to move 15.8 million [cubic yards] of sand.” Meanwhile, “a project in the Netherlands moved 28.1 million [cubic yards] of sand at a cost of $55.5 million.”

While a full repeal of the Foreign Dredge Act seems unlikely right now, a waiver process could be established to permit cheaper foreign dredges to act in a limited capacity in U.S. waters. Conditions could be set so that waivers could be issued when existing U.S. capacity is in full use, and there is still a backlog of maintenance dredging requirements throughout the United States, or in unique times of crisis where rivers like the Mississippi or other navigation- and shipping-critical corridors are too low.

Larger, less expensive European dredgers, even if they are not the right dredgers for the Mississippi, could work on other projects and free up smaller, specialized U.S. dredging vessels for the Mississippi.

If the Army Corps of Engineers could entertain bids from international dredging firms, and an international firm won, the firm could request a waiver through this new process. The waiver would allow the foreign vessels access to U.S. waters and permit them to dredge material in the United States.

Usually, this would also require a limited waiver of the Jones Act, which forbids the U.S.-port-to-port movement of goods (and valueless material, such as dredged material), but the Dutch firm Van Oord estimated it could execute contracts in the U.S. (like port deepenings) for 60% of the current costs and three times faster than today’s U.S. timelines (thanks to their larger, higher-capacity dredges), even using mostly U.S. crews and support vessels.

Waterborne transportation remains critical for the country, but agricultural shippers and port authorities have the most to gain from this waiver process. Freeing up U.S. dredgers and bringing in cost-effective European dredgers could help lower prices for ports looking to sustain and expand navigable channels. It appears the droughts hitting the Mississippi in recent years are not going to disappear. Shippers, the Army Corps, and Washington lawmakers and regulators must work together to create a modern, sustainable inland waterway system.