In the early morning hours of March 26, the 1,000-foot container ship MV Dali lost power as it was exiting Baltimore Harbor via the Patapsco River and struck a support pier of the Francis Scott Key Bridge, causing a catastrophic failure. Six construction workers had been on the bridge performing routine maintenance and were killed. The wreckage of the collapsed bridge blocked shipping channels to the Port of Baltimore.

While restoring maritime access to the port is the main immediate concern, recovery efforts will soon turn to replacing the Key Bridge. As policymakers work to understand and guide recovery, they should seek to minimize red tape that would unnecessarily increase construction costs and delay project delivery.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is leading efforts to clear the wreckage in phases, gradually allowing deeper-draft vessels to resume operating in and out of the port. Restoring access to the port is the top priority given its economic importance, with its closure to marine traffic estimated to cost $15 million per day in lost economic activity.

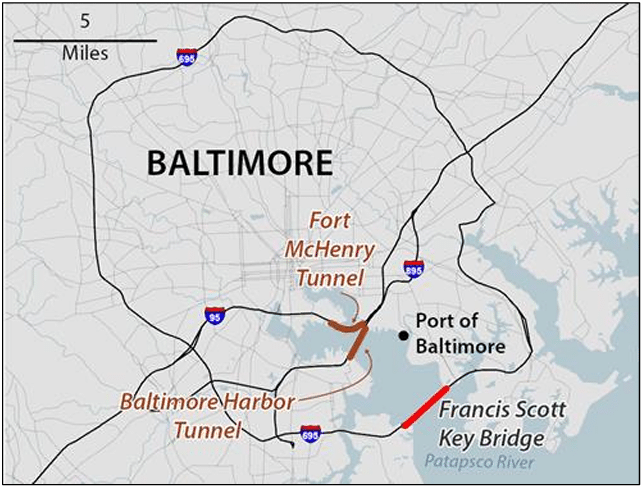

Although it served as a southern segment of the I-695 Baltimore Beltway eastern loop, the Key Bridge itself carried less highway traffic than nearby tunnel crossings (see Figure 1). According to Maryland Transportation Authority toll transaction data (see Tables 2-2 and 2-3 of the CDM Smith report), in 2023, the bridge carried 30,370 cars and 3,748 commercial vehicles per day.

For comparison, the I-95 Fort McHenry Tunnel just upriver from the Key Bridge carried more than three times as many cars and trucks. Together with the I-895 Baltimore Harbor Tunnel, which carried twice as many vehicles as the Key Bridge, these two alternative river crossings will be able to absorb most of the diverted bridge traffic without large increases in congestion.

Figure 1: Map of Baltimore Harbor Crossings

Source: Congressional Research Service (2024)

However, the Key Bridge served as an important route for oversized trucks and those carrying hazardous materials that are prohibited from using the Fort McHenry Tunnel. The Harbor Tunnel has even more stringent size restrictions that prohibit standard semi-trucks, in addition to also forbidding any vehicles carrying hazardous materials.

Until the bridge is replaced, trucks barred from using these tunnels will need to detour around the western loop of I-695, adding about 30 miles per trip. The longer trip around the north of Baltimore increases travel distance and time, which in turn increases population exposure to the risks posed by hazmat trucks. This should add further urgency to restoring a Patapsco River crossing that can accommodate these vehicles.

As policymakers turn their attention to replacing the Key Bridge, they will need to answer important questions about construction time, cost, and financial responsibility. Some factors will be outside the control of policymakers, but most are within their control.

The primary outside factor that will dictate construction time and cost is how much of the reinforced concrete bridge foundation is salvageable and suitable for reuse by a replacement bridge. Determining the extent of damage to the Key Bridge substructure will require underwater inspection, which cannot be conducted until the wreckage has been cleared. If large portions of the Key Bridge foundation can be reused, this could significantly reduce construction costs, delivery time, and environmental impacts, according to a 2018 report on reusing foundations published by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA).

Construction cost and time factors entirely within the control of policymakers are largely tied to policies governing financial responsibility. Maryland is seeking federal assistance to replace the Key Bridge. The U.S. Department of Transportation has already authorized $60 million in “quick release” funding under the Emergency Relief (ER) program.

Preliminary cost estimates for rebuilding the Key Bridge range from $400 million to more than twice that. Under current law (23 U.S.C. § 120(e)(4)), the federal government could cover up to 90% of the cost of bridge replacement if costs exceed Maryland’s annual federal-aid highway funding apportionment, which, in the 2024 fiscal year, is $828,287,771. Otherwise, the Key Bridge project would be eligible for an 80% federal share under the emergency relief program.

Congress authorizes $100 million per year in ER program funding, which currently has a $1.9 billion unobligated balance. Hours after the bridge collapse, President Biden said, “It’s my intention that [the] federal government will pay for the entire cost of reconstructing that bridge, and I expect to—the Congress to support my effort.”

It is important to note that the Key Bridge was financed and maintained with toll revenue, not federal aid or state grants like most bridges on the National Highway System. As such, federal prevailing wage requirements under the Davis-Bacon Act and Buy America domestic content requirements, both of which are designed to limit contracting competition and increase construction costs, did not apply.

However, FHWA’s Emergency Relief Manual makes clear that toll facilities that were not federally funded but are receiving ER funding must comply with typical federal-aid funding requirements. These include the Davis-Bacon Act, which the president may suspend “during a national emergency,” as well as Buy America, which can be waived at the discretion of FHWA in narrow circumstances.

President Biden has publicly supported using “union labor and American steel” to rebuild Key Bridge, so Congress would need to enact exemptions to avoid triggering these costly requirements.

Similarly, if Congress does move forward with the supplemental emergency relief appropriation requested by the president, it should also waive National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requirements.

Under current NEPA implementing regulations (23 C.F.R. § 771.117(c)(9)), replacing the bridge should qualify for a “categorical exclusion” from environmental review requirements as long as the new bridge is built within the existing right-of-way and of a similar design of the original bridge.

These NEPA categorical exclusion rules allow for the new bridge to be designed to meet modern standards that did not exist when the original bridge was built, such as new redundancy requirements that were lacking in the “fracture critical” design of the original Key Bridge. However, these rules do not clearly exempt the installation of bridge protection systems designed to deflect ship collisions and prevent structural damage.

As with Davis-Bacon and Buy America requirements, a congressional supplemental emergency relief appropriation could explicitly exempt the construction of the Key Bridge replacement from NEPA requirements. Failure to do so could substantially increase the cost of the project and delay construction.

Congress will likely face growing pressure to shoulder the costs of replacing the Key Bridge. If Congress decides to proceed with supplemental emergency relief funding, as President Biden has requested, it should explicitly waive costly federal regulations to help ensure that taxpayer dollars are not wasted and construction is completed in a timely fashion.