When President George W. Bush’s administration awarded the first large-scale U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) discretionary grants under the Urban Partnership Agreement and Congestion Reduction Demonstration Program, proponents of a quantitative transportation project selection process considered the early grants a successful tool to improve mobility. Finally, the thinking went, there was an alternative to the federal government’s decades-old formula-funding, which had previously awarded federal transportation funds based on complex formulas that seemed largely written to satisfy the most powerful politicians rather than project merit. Five of the six initial grants went to major cities —Atlanta, Los Angeles, Miami, Minneapolis, and Seattle—and led to some of the earliest variable-tolling projects in the United States.

Each of those tolling projects met four basic criteria recommended by researchers:

- They were awarded based on a cost-benefit analysis;

- Each project involved interstate infrastructure;

- All projects were directly transportation-related;

- And, the selection process was designed to minimize politics.

Unfortunately, the discretionary grant selection process eventually careened into a ditch and has not recovered. Two presidential administrations later, the discretionary grant program has turned into more of a politicized tool than one based on cost-benefit analysis. Before examining the Biden administration’s Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity (RAISE) grants, it’s useful to recap the last 12 years of discretionary grants.

The Obama administration’s Transportation Investments Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) grant metrics were opaque and subjective. Even projects that scored well in the cost-benefit analysis did not necessarily receive federal funding. Many projects that were rated as “recommended” (the second-highest category) were prioritized and funded ahead of projects that were rated “highly recommended” (the highest category). During this period, a large emphasis was placed on providing federal funding for local multimodal transit hubs, regardless of their merits. The Eno Center for Transporation found a disproportionately large number of projects were funded in the districts of members serving on congressional transportation and finance committees and in districts won by members of the Democratic Party.

In 2017, the Trump administration changed the name of the program to Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development (BUILD). With a focus on federal infrastructure (highway, freight, and ports), the administration worked to prioritize funding interstate projects instead of local multimodal hubs and recreational trails. However, the Congressional Research Service found rural projects with low scores were funded over urban road projects with higher scores, largely for political purposes.

The Biden administration changed the name of the discretionary grant program to RAISE, but kept the worst BUILD element—dedicating 50% of all of the program’s funding to rural areas despite the program’s original intent being to address urban traffic congestion.

Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg has strengthened criteria in ways that intend to benefit projects in communities of color and aims to improve racial equity. For example, under RAISE, project sponsors in areas of persistent poverty do not have to provide any local matching funds to receive federal funding.

Some previous transportation projects have undeniably had a negative impact on their communities but these limited federal dollars should be targeted to cities where they can do the most good. Rebuilding communities is far more complicated than adding a recreational trail here or there, as a local park authority is planning with the Brickline Greenway in St. Louis.

Additionally, new to the RAISE program, funded projects are required to have “a significant local or regional impact.” Since the projects are to receive federal funding, the requirement should be for projects to have a “national impact,” not the other way around. Federal funding is limited and federal decision-makers in Washington, D.C., are not in the best position to make decisions on local or regional projects.

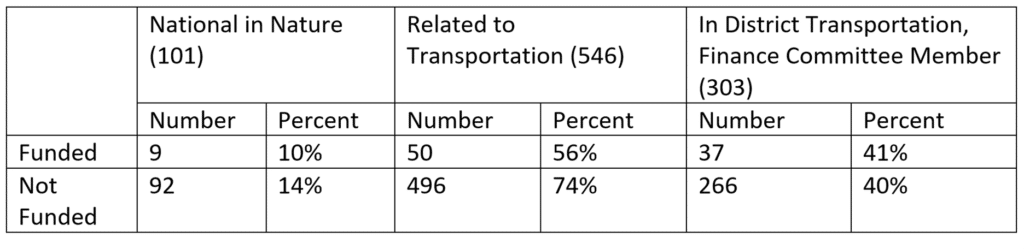

The federal government doesn’t share the complete data that would allow researchers to examine the rigor of the cost-benefit analysis being done, so we’ve attempted to quantify how many of the federal grants met three of the four basic criteria outlined in the original program noted in this pieces’ second paragraph—projects being interstate, related to transportation, and awarded without consideration of political representation.

My intern Mae Baltz and I created a spreadsheet that included all 763 grant applications. We examined how the 90 projects that were awarded funding in 2021 differed from the 673 projects that did not receive funding. We categorized each project into national interest or local interest, transportation-related or not transportation-related, and whether or not the project is in a congressional district of members serving on a transportation or funding committee (the House Transportation and Infrastructure, House Finance, Senate Banking, Senate Finance, Senate Environment and Public Works, and/or Senate Finance) or not in one of those districts. We also examined the federal share of funding and the type of applicant.

As the summary table shows, of the 90 projects funded with Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity grants in 2021, only nine projects (10%) were national in nature.

Of the 90 projects funded by RAISE grants, 50 projects, 56%, were related to transportation. The other projects funded were primarily focused on environmental remediation, economic development, or other factors. Of the projects not selected, 496 (74%) were related to transportation.

Of the 90 projects funded, 41% were located in congressional districts represented by members of a transportation or financing committee. Only 15 of the 90 projects funded by RAISE, or 17%, were projects submitted by a state government. State governments don’t have the monopoly on good transportation projects but they do own the vast majority of the country’s transportation infrastructure, including, most notably, Interstate highways that are in desperate need of reconstruction.

Breakdown of 2021 RAISE Grants

In a nutshell, the projects that were federally funded using the Biden administration’s Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity grants were less likely to meet the three objective criteria originally recommended by researchers (national-in-nature, related to transportation, political independence) than the projects that were not funded in 2021.

The last three presidential administrations have shown that the executive branch does not allocate discretionary federal grants to their best uses. A program originally intended to improve mobility is getting further and further away from its purpose. RAISE grants in 2021 were far more likely than the TIGER Grants and the BUILD Grants to be awarded to local, non-transportation projects.

Going forward, the Congressional Budget Office and Congressional Research Service need to continue to examine where and how these discretionary grants are being awarded. And members of Congress need to use oversight power more effectively to determine why the executive branch is directing this taxpayer funding to non-transportation projects and why so much of it ends up in the districts of members on transportation and/or finance committees.

The massive bipartisan infrastructure bill that was recently signed into law failed to address the need to rebuild the Interstate Highway System. This federal program, originally designed to combat urban traffic congestion, is sending money to hiking and walking trails and other non-transportation projects. Federal policymakers should get back to the core principle that federal transportation funding should be based on cost-benefit analysis and programs that are national in scope.