As opioid overdoses continue to climb in the United States, politicians and the public are understandably trying to determine what or who is responsible for this public health crisis. Purdue Pharma, which makes OxyContin, and its owners, the Sackler family, have come under fire and are being targeted by numerous lawsuits.

On January 15, 2019, Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey filed a 274-page pre-hearing memorandum alleging the Sackler family and their company Purdue Pharma “created the [opioid] epidemic and profited from it through a web of illegal deceit” by enticing doctors to prescribe their medication and peddling “falsehoods to keep patients away from safer alternatives.”

“We are confident the court will look past the inflammatory media coverage generated by the misleading complaint and apply the law fairly by dismissing all of these claims,” the Sackler’s attorneys said in a statement.

This is no small accusation from Massachusetts. If the state is going take this action against Purdue Pharma, one would hope that their case rests on solid evidence. But, unfortunately, the facts do not seem to support the commonwealth’s claims.

Evaluating the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Accusations

Massachusetts’ accusation that Purdue Pharma “created” the opioid epidemic by intentionally getting pain patients addicted to their products is not supported by the relevant academic literature on the subject. An abundance of evidence suggests that long-term opioid management for chronic pain does not lead to high rates of addiction. A comprehensive literature review of 26 studies found that addiction occurred in only .27 percent of patients treated with opioid painkillers for chronic pain. Another study found that for opioid pain patients with “no previous or current history of abuse/addiction, the percentage of abuse/addiction was calculated at 0.19 percent.”

Purdue Pharma advertised that the addiction rate for OxyContin was one percent, and studies continually agree or suggest that claim was conservative.

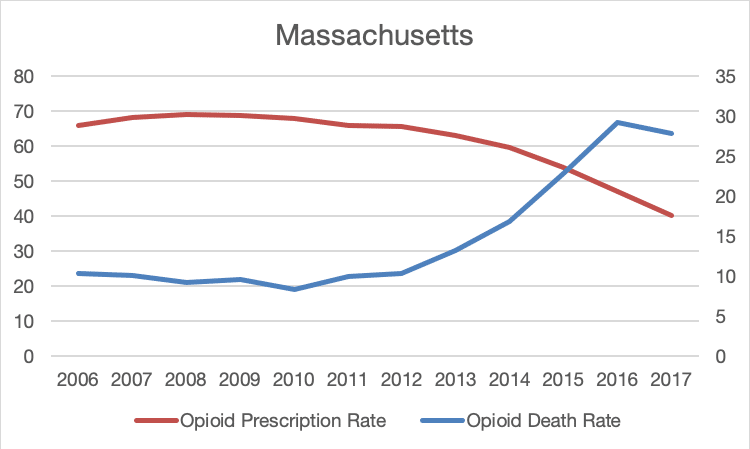

Contrary to the commonwealth’s narrative, prescription opioid addiction rates have not been on the rise. While prescribing rates have fluctuated over the past 15 years, nonmedical prescription opioid use has remained constant since 2002. Furthermore, the most recent spike in opioid overdose deaths reflects not prescription opioid deaths, but those of illicit opioids such as heroin and fentanyl—street narcotics that are not manufactured or sold by Purdue. In fact, the Journal of the American Medical Association has documented that opioid overdoses related to fentanyl “account for nearly all the increase in drug overdose deaths from 2015 to 2016” and after.

Additionally, the introduction of “safer alternatives” to OxyContin has only increased overdoses. Facing public pressure, Purdue Pharma introduced an “abuse-deterrent” reformulation of OxyContin on August 9, 2010. According to Evans et al. (2018), “[w]hen the new pills were crushed, they did not turn into a fine powder, but instead a gummy substance that was much more difficult to snort or inject.” But the reformulation of OxyContin only exacerbated the problem. The authors concluded “[t]he new abuse-deterrent formulation led many consumers to substitute to an inexpensive alternative, heroin” and to a quadrupling in heroin deaths.

Evaluating the Impact of the State’s Restrictions on Prescribing

Over the past five years, in its efforts to curb opioid use, Massachusetts has adopted several policies that make it more difficult for pain patients to receive prescription opioids from physicians.

In 2016, the Massachusetts State Legislature voted to limit first-time opioid prescriptions to a seven-day supply for adult chronic pain patients. Yet, there are unintended consequences of this law. When a suffering patient is cut off from legal opioids, but still desires to use the drug, the black market meets this demand. Drugs acquired through illicit sources, however, are inherently more dangerous than those purchased legally for a variety of reasons, including consumers’ lack of information about the true contents, potency, and quality of the substances. Shifting people from doctor-prescribed opioids to the black market contributes to the number of overdoses on highly potent illicit drugs, such as fentanyl.

In Massachusetts and many other states, deaths from opioids that are most commonly acquired on the black market accelerated the number of opioid deaths only after prescribing rates decreased, which indicates the troubling relationship between restrictions on prescribing opioids and increased overdose deaths.

Concurrently in 2016, Massachusetts strengthened its Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP), a statewide database that requires physicians to check a patient’s prescribing history before issuing them drugs. However, academic evidence examining PDMPs in other states suggests that they may also be associated with increased overdose deaths. According to one National Institutes of Health study examining the implementation of a PDMP in New York, “[p]rescription opioid morbidity leveled off following the implementation of a mandated PDMP” but “morbidity attributable to heroin overdose continued to rise.”

It’s understandable for state leaders and the public to seek answers to, and assign blame for, opioid-related problems. But Massachusetts should look inward at its own policies. By increasing access to opioids through legal channels, lawmakers could work to decrease the harms of the black markets and reduce overdoses and the risks surrounding drug use. Massachusetts actually reduced overdose deaths with this approach when it expanded medication-assisted treatment in 2017. But the attorney general’s unfounded lawsuit ignores what has worked and runs the risk of undermining the commonwealth’s current public health success.

Massachusetts Data:

| Year | Opioid Death Rate | Opioid Prescription Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 10.28067651 | 66 |

| 2007 | 10.09086599 | 68.2 |

| 2008 | 9.213217504 | 69.2 |

| 2009 | 9.54337117 | 68.9 |

| 2010 | 8.384714528 | 67.9 |

| 2011 | 9.943019666 | 65.9 |

| 2012 | 10.39700614 | 65.7 |

| 2013 | 13.2679419 | 63 |

| 2014 | 16.90038616 | 59.6 |

| 2015 | 22.81283088 | 54 |

| 2016 | 29.21410104 | 47.1 |

| 2017 | 27.88703317 | 40.1 |