When President Obama signed the stimulus bill back in February, his economic team predicted that the stimulus would keep unemployment below 8%. In June, the unemployment rate was 9.5%. In light of this, Paul Krugman thinks his original critique of the stimulus package, that it should have been bigger, has been proven correct: “The bad employment report for June made it clear that the stimulus was, indeed, too small”. Therefore, Krugman is calling for more stimulus.

There a lot of problems with more stimulus, especially since Krugman’s preferred form of stimulus is increased government spending. For example, it is difficult for the government to spend quickly enough to significantly stimulate the economy, and there are a limited number of “shovel-ready” projects that the stimulus can fund.

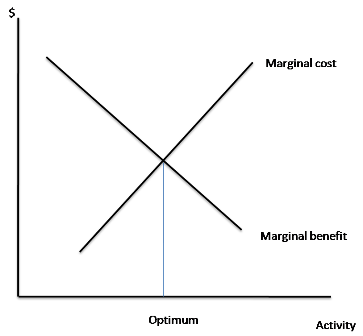

But aside from those concerns, there’s another important consideration that Krugman continually seems to brush aside. Krugman recently wrote a blog post referencing this graph:

The graph illustrates the basic framework economists use to think about almost everything. In the context of stimulus, the government should target a spending level at which the benefit associated with spending an additional dollar equals the costs associated with spending that additional dollar. The part of this calculation that enthusiastically pro-stimulus pundits often conveniently ignore when they push for more government spending, of course, is cost.

Krugman addresses this somewhat in the same post:

The marginal cost is the way stimulus adds to debt. This cost gradually rise[s] as you add more debt, since the risk of an eventual crisis is increased. But does anyone really think that, say, another $500 billion in borrowing would be the straw that breaks the camel’s back?

True, the extent to which additional deficit spending increases the likelihood of a debt crisis is part of the marginal cost of the stimulus package. But the main cost (and what economists usually focus on when they analyze marginal cost) is the opportunity cost, which is the value of the next-best alternative way to spend the money.

Assuming that the Obama administration is correct in claiming that the stimulus will save or create 3.5 million jobs, then each job that the stimulus saves comes at a cost of $225,000. Rather than just arguing that unemployment is too high, and therefore we need more spending, those who want a second stimulus (and who defend the first one) need to justify why a job creation program that spends nearly a quarter of a million dollars per job is the best way to spend public money.

For more, check out Reason Foundation’s Taxpayer’s Guide to the Stimulus, which lays out the first stimulus bill in all of its porkilicious magnificence.