It’s no secret that most school finance systems are outdated. But where can state policymakers find a blueprint for positive reform? Perhaps the best model to emulate is California’s Local Control Funding Formula.

In 2013, California modernized its school finance system by streamlining more than 30 categorical grants into a simple weighted-student formula that bases funding on individual students. California’s experience provides valuable lessons for policymakers in other states.

Background

Before transitioning to Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), categorical funds accounted for about one-third of state K-12 education funding. These grants were deployed for a wide range of purposes such as professional development, technology, summer programs, and even oral health assessments. As a result, California’s funding system was a complex web of mandates that forced school districts to spend education dollars on programs that didn’t always align with local needs. Importantly, it also failed to effectively target resources to students who required additional support.

LCFF sought to achieve several policy objectives, including to increase local spending flexibility and provide additional funding for targeted student groups. Ultimately, this bi-partisan reform was driven by the principle of subsidiarity—that local stakeholders are in a better position than legislators to make spending decisions. To do this, LCFF eliminated about three-quarters of the state’s categorical programs—nearly half of all categorical funding—and streamlined dollars into a weighted-student formula that delivers unrestricted funds to districts based on students.

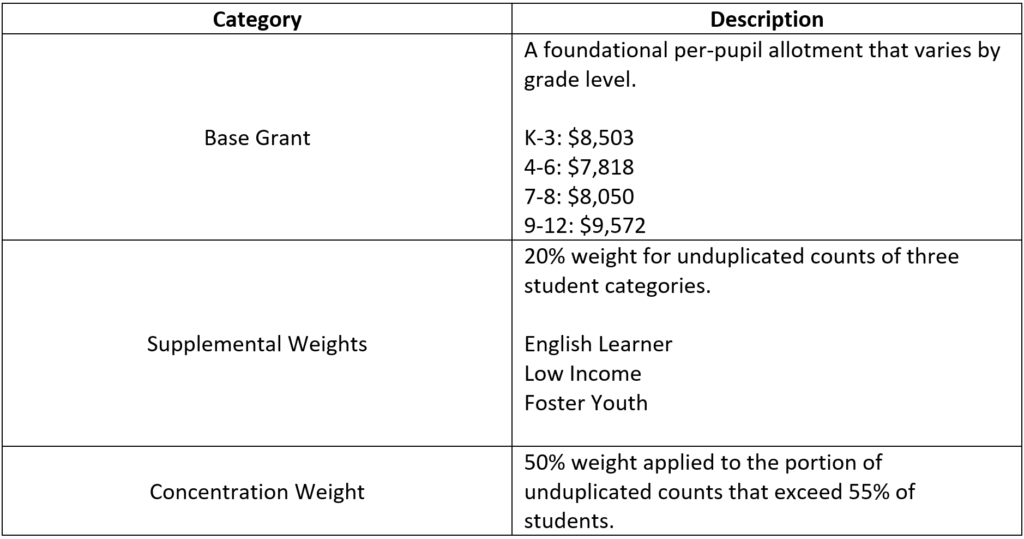

Table 1 summarizes the formula and shows funding levels for the 2019-20 school year.

Table 1: 2019-20 Local Control Funding Formula

The transition to LCFF employed a hold harmless provision so that school districts wouldn’t receive less state aid than they did before the legislation was enacted. During the phase-in period funding was based on this revenue floor, its LCFF target funding level, and the difference between these amounts (i.e. the “need” or “gap”). Each year districts not receiving their full target funding would get a portion of their calculated need based on state appropriations.

Although LCFF was scheduled to be phased-in over eight years, the transition was complete by the 2018-19 school year when all school districts were funded at their LCFF target levels.

Research

It’s still early but several studies have examined the effects of California’s school finance overhaul, and the results are largely positive. Five themes have emerged indicating that, despite a couple of notable shortcomings, Local Control Funding Formula provides a better foundation for California’s education system.

1. There is widespread support for the Local Control Funding Formula

LCFF remains a popular reform. In a survey of superintendents, 82 percent agreed that it is leading to greater alignment among goals, strategies, and resource allocation decisions, and 74 percent indicated that the financial flexibility enabled their district to match spending with local needs. A separate survey found that, of those familiar with the law, 72 percent of likely voters and 84 percent of parents viewed it positively.

Researchers from the Local Control Funding Formula Research Collaborative (LCFFRC) also concluded that there is “little enthusiasm” for returning to the prior funding system that relied heavily on categorical grants with the vast majority of stakeholders embracing the reform.

2. LCFF has prompted cultural shifts within school districts

Removing spending mandates is changing the way that districts operate. A study published by Policy Analysis for California Education (PACE) indicates that districts are focusing less on compliance and more on aligning spending with students’ needs.

Research also shows this has spurred greater collaboration between financial and academic leaders who are beginning to incorporate student achievement, attendance, course enrollment and other data to help identify budgetary priorities. Additionally, the LCFFRC found evidence that some school districts are using their flexibility to give school leaders more say over spending decisions. San Mateo Foster City School District, for instance, allows schools to decide how two-thirds of their supplemental funds are spent. Principals have indicated that this has helped them achieve buy-in from teachers and allowed schools to better support priority student groups.

3. School districts are customizing, not overhauling

Prior to adopting LCFF, some policymakers feared that financial flexibility would result in overzealous changes in spending patterns, but research by Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab suggests that this hasn’t been the case. Instead of radical shifts, it appears that districts are using their autonomy to customize spending. For example, some districts are prioritizing things such as staff development and health services, while others deprioritize them. While Edunomics also found evidence that many districts beefed up their teaching staffs with their additional dollars, it appears that they didn’t simply bargain away their new dollars with across-the-board salary increases, another concern that policymakers sometimes have with local flexibility.

4. LCFF has helped improve funding equity

LCFF seems to be accomplishing its aim of improving funding equity. Analysis by Education Trust-West showed “dramatic” changes in allocation patterns: only three years after the reform the state’s highest poverty districts went from a funding gap to receiving $334 more per pupil compared to the lowest poverty districts.

Additionally, Edunomics Lab found hiring growth in services for disadvantaged students, and researchers at PACE concluded that the examined districts “showed a strong alignment with [former] Governor [Jerry] Brown’s vision of closing opportunity gaps by distributing greater resources to those with greater needs.”

5. Some challenges persist

LCFF has some notable shortcomings. Most importantly, improving equity among districts doesn’t necessarily mean that individual schools always get their fair share of the funding pie.

A study of the Los Angeles Unified School District found that the district is failing to target its education dollars to students in low-income elementary schools. According to Bruce Fuller, the study’s director, “We continue to see little fairness in how LAUSD distributes dollars to schools, ignoring whether they serve high or low shares of low-income children.”

This issue isn’t unique to LCFF or California, but it’s something that policymakers across the country must be mindful of when reforming school finance systems.

LCFF also created new administrative burdens as districts are now required to complete a Local Control Accountability Plan (LCAP) annually. This three-year planning document “describes the goals, actions, services, and expenditures to support positive student outcomes that address state and local priorities” and must be developed in consultation with community stakeholders. While these requirements might sound good in theory, they seem to be producing little value and reinforcing a compliance mindset.

According to one superintendent, “The LCAP is meant to demonstrate ‘due diligence’ to assess and meet needs but it’s become too much of a compliance document—too much about dotting all the i’s and crossing all the t’s.” Los Angeles Unified’s LCAP exemplifies this problem.

Fortunately, a provision in the Every Student Succeeds Act might help address these issues. All states will soon be required to publicly report school-level expenditures so that stakeholders can see exactly how districts are allocating education dollars. California and other states can use financial transparency as a tool that supports financial flexibility and accountability.

Conclusion

California’s Local Control Funding Formula reform demonstrates how funding systems can be improved so that they are more equitable, transparent, and flexible. State policymakers evaluating reform options would be wise to consider the Golden State’s approach to allocating education dollars.

However, a word of caution is also warranted: There isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution to school finance, and weighted-student formulas should be based on the unique needs of a state’s students. Policymakers should not compromise on distributing education dollars fairly and would be wise to allow the educators closest to students to make spending decisions.