The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated the need to update Mississippi’s K-12 education funding model, in particular the way that the school finance formula counts students.

Mississippi differs from most states in the fact that they currently use an average daily attendance (ADA) model to count kids. This way of counting students is not all bad, but the COVID-19 pandemic has brought to light the already existing deficiencies of the average daily attendance model and some Mississippi school districts are at risk of losing a significant amount of funding because their average daily attendance has declined during the COVID-19 outbreak.

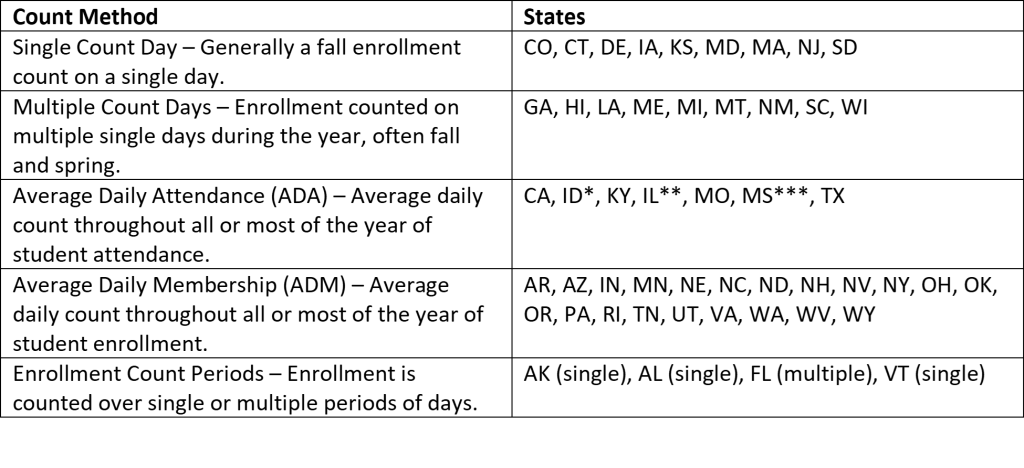

Surprising variation exists in how states measure public school enrollment. These measurements are important because they ultimately affect how education dollars are allocated to students and schools. Every way of counting kids comes with important tradeoffs: some are more accurate than others; some impose a greater administrative burden; others result in more budget stability.

This commentary will survey the current student counting methods used across states and make policy recommendations that Mississippi policymakers could employ to address funding shortfalls resulting from a decline in average daily attendance counts.

Key Considerations: Accuracy, Predictability and Budget Stability

There are some key considerations states make when they take different approaches to counting students. Keep in mind that there are drawbacks to each of these considerations.

The first priority for legislators weighing different student count methodologies should be accuracy. Accuracy is the key to fair funding insofar as the entire point of counting student enrollment is to correlate enrollment with funding. To be funded, a student must be counted.

To the extent that any other factors obscure the principle that funding should be determined by the true number of students a district currently has enrolled, inequities will emerge. Concerns over accuracy and funding equity are the reason some states opt to use average daily membership (ADM). This way of counting differs from ADA in that ADM averages student enrollment numbers—rather than attendance numbers—over much of the school year. Enrollment is considered more accurate in this case because it counts the number of students a district expects to serve, not the number that shows up on a given day. North Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia, along with many other states, use ADM.

Second, there is generally some acknowledgment that school districts must be able to reliably craft their yearly budgets. If state funding varies too much over the course of a year due to attendance fluctuations, districts won’t be able to make confident hiring or programmatic decisions. If, as it’s generally assumed, student bodies are largest at the beginning of a semester, districts must structure their staffing and budgets without good knowledge of which students and how many of them will end up withdrawing. These budget concerns are the reason some states use single-day enrollment counts at the beginning of the year (Colorado, Maryland, Massachusetts) or at only several points over the course of the year (Georgia, South Carolina, Louisiana).

A third key consideration for state lawmakers when deciding on a student counting system is that districts struggle to adjust their cost structures when student bodies are changing substantially over a short span of years. When student bodies are shrinking or growing rapidly, districts must make long-term decisions about consolidating or expanding school facilities. With staffing, they often can only downsize through attrition when populations are shrinking. Likewise, schools face additional hiring costs when student populations are growing. Because these long-term investments take time and often lag behind the speed at which student populations are changing, some states (Maine, Nevada, North Carolina) allow districts to incorporate older or projected student counts so that they have a financial cushion to accommodate substantial increases or decreases in student populations.

Lastly, many state policymakers believe funding decisions should emphasize school attendance metrics. Under this model, the reigning assumption is that time spent in a physical classroom directly translates into student achievement. A primary rationale for the small number of states (Mississippi, California, Illinois) that count students through attendance, rather than enrollment, is that they want to encourage districts to get students in their classrooms.

The most important split on student counting policy decisions is between the majority of states that use enrollment to determine school funding and the seven states, including Mississippi, that use attendance.

Summary Table of State Student Counting Mechanisms

Most states use some form of enrollment count period or average daily membership (ADM), which is the average number of enrolled students over a certain period of time, to determine school funding. As mentioned, only seven states use average daily attendance (ADA). That said, some states using ADA also use count windows during the school year. For instance, Mississippi uses ADA from October and November of the previous year, and Illinois uses the highest three-month ADA from the previous year or an average of the previous two years.

As mentioned earlier, the main rationale for states that use ADA is that they want to incentivize districts to get students in school. Additionally, proponents of ADA argue that relying on attendance counts rather than enrollment counts can save states some money since some students will be absent on any given day.

There are problems with using ADA to count students for funding purposes. First, there’s little evidence that ADA provides an incentive to schools to boost their attendance. This shouldn’t be surprising since attendance issues are largely beyond the scope of a school’s control. Chronic absenteeism and frequent absences are often related to poverty, chronic health issues, or other community-related factors. Even in cases where low student attendance rates may be attributed to school-level factors, such as poor teacher quality or geographic challenges, schools often have few tools to fix these problems. Thus, the districts are being penalized for issues largely beyond their control.

A second problem with using ADA is that it tends to disproportionately penalize districts that serve more disadvantaged students. Because students from poor and minority communities are more likely to miss school, ADA counting creates funding inequities between districts that serve different populations. More generally, it arbitrarily favors districts with higher attendance rates and disfavors districts with lower attendance rates.

Third, it is very unlikely that using an attendance-based formula, rather than one based on enrollment, saves the state money. Public education budgets and per-pupil funding amounts are generally determined by available resources. Any increase in the number of counted students, all else being equal, simply leads to the same number of resources being spread out over a larger group of students.

The final problem with ADA is that it presumes districts are able to adjust their daily costs when students don’t show up. This is a dubious assumption because, as mentioned, districts must make hiring and programmatic decisions based on enrollment and the students they expect to serve. Because they usually lack good information to know which students will be missing on a given day, districts can’t be expected to tailor daily costs accordingly.

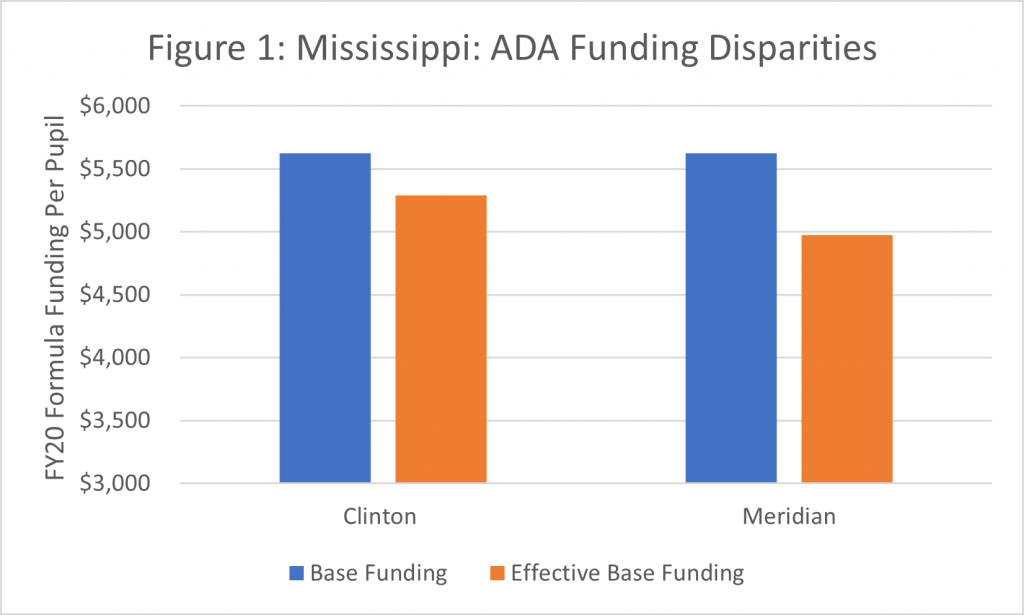

Funding districts based on ADA often creates substantial per-pupil funding inequities between districts with different attendance rates. Take a simplified example from Mississippi. The Clinton and Meridian school districts are very similar in size. Clinton Public School District enrolled 5,310 students and Meridian Public School District enrolled 5,232 in the 2018-2019 fiscal year (FY). However, Clinton had an average daily attendance rate of 94.07 percent while Meridian had an ADA rate of 88.44 percent. In FY19-2020, Mississippi’s funding formula funded each student at $5,626.22. Despite enrolling a very similar number of students, these two districts effectively received different base funding amounts due to their different ADA rates. See Figure 1.

As Figure 1 illustrates, Clinton Public School District received an estimated $5,292.59 per enrolled pupil while Meridian Public School District only received $4,975.83 per enrolled pupil. This is a gap of $316.76 per student. Multiplied over Meridian’s entire student body, this disparity comes out to $1.66 million. In other words, if Meridian had produced the same attendance rate count as Clinton, they would have received $1.66 million more in funding. Since it’s unlikely that Meridian is able to adjust daily staffing and operational costs because of having a lower attendance rate, they are forced to plan on serving a similar number of students as Clinton on a smaller budget. Making matters worse, U.S. Census Small Area Income and Poverty data show that Meridian has a child poverty rate of 39.6 percent while Clinton’s child poverty rate is 13.6 percent.

Funding disparities like that illustrated in Figure 1 persist across Mississippi and the six other states that continue funding districts based on ADA.

Recommendations

Policymakers in Mississippi should consider several principles as they look at reforming their student counting policies. The overall goal should be to ensure that all students are fairly funded at any given point in a school year and from year to year.

- Use enrollment, not attendance. Because of the inequities and problems created by the use of ADA, districts should be funded based on enrollment.

- Prioritize accuracy. Student counts shouldn’t be outdated or only reflect a small snapshot of what a district student body looks like during the year. An accurate count relies on multiple data points that provide a true picture of what enrollment actually is and how funding should be allocated.

- Include considerations for district budget planning. While accuracy should be the top priority, it is true that districts can only do so much to scale their costs over the course of a school year if enrollment shifts significantly in one direction or another. Enrollment counts should be averaged out over most of the entire school year, but adjustments to payment schedules should be limited to reasonable intervals (i.e., each semester or quarterly). Additionally, the state should work with its districts to provide accurate projections for future payment periods and future years.

- Avoid creating perverse incentives. If enrollment counting periods are too narrow, districts are driven to hit a “high-water mark” during the recorded period. This can create a perverse incentive whereby districts push to enroll a maximum number of students for financial reasons during the counting window but then are later inclined to expel students or neglect retention strategies.

- Consider funding fairness across different delivery models. Beyond basic concerns about how and when students are counted, state leaders should consider how closely student counts and school funding are attached to scheduling or learning time requirements. This is especially important now as education becomes increasingly “unbundled” and students are enrolling in virtual courses, competency-based programs, or getting course credit through options other than regular classrooms. Dollars should be based mostly (or fully) on enrollment – without differentiating funding based on learning hours, learning models, or school schedules. Likewise, school funding decisions shouldn’t be hampered by overly bureaucratic reporting requirements like those imposed on at-risk funds used to assist underserved students.

Several states strike a reasonable balance between these priorities. Nevada counts students via ADM over the course of the entire school year, divided quarterly. Payments to school districts are based on the average daily enrollment for the immediately preceding quarter. The state does include a declining enrollment exception whereby districts with enrollment of 95 percent or less of the previous year may instead use the previous year enrollment count for funding purposes. This provision isn’t ideal since it divorces some funding from being directly based on current students. Nonetheless, Nevada has many strong components to its student counting method since it incorporates and regularly updates current student counts for most of its districts (only making exceptions for those with substantial enrollment declines).

Another example state is Washington, where schools are initially funded based on enrollment estimates at the beginning of the year, and state aid is subsequently adjusted over the course of the year. Enrollment is counted on the first day of each month, and payments are made monthly based on updated enrollment counts from the prior month.

In the context of the pandemic, it’s also important that districts have flexibility in how they count their students so they can educate students in a way that fits local needs and acknowledges public health risks without fearing the loss of funding.

While there’s no perfect student counting model, following these principles can promote funding fairness and better ensure that all students are counted equally.

A version of the column was previously published by the Mississippi Center for Public Policy.