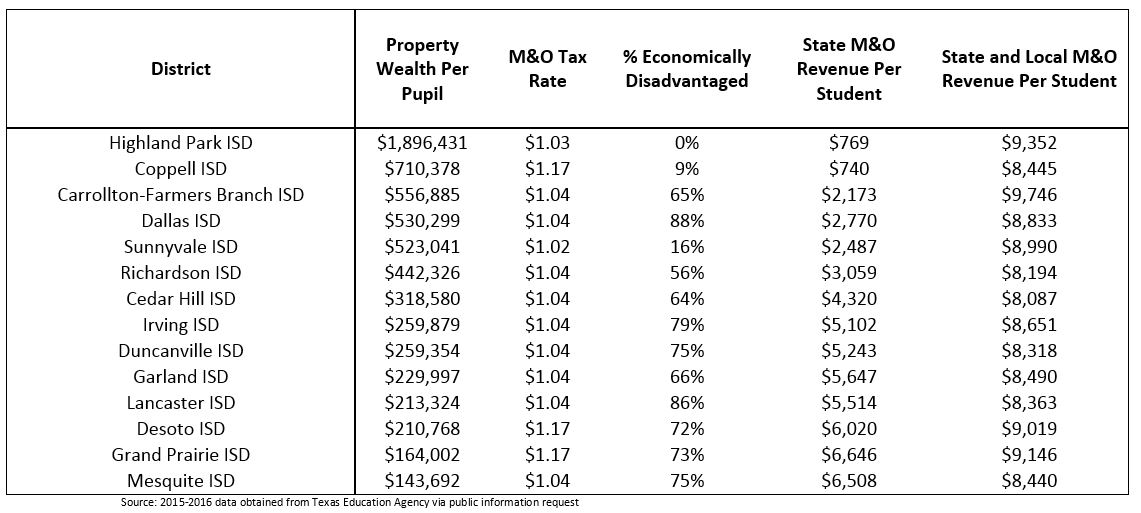

I previously addressed the question of whether local education revenues are compatible with the principles of student-centered funding. To further illustrate how they perpetuate funding inequities it’s useful to compare the finances of neighboring school districts. Dallas County is the second largest county in Texas and its 14 districts serve more than 443,000 students. Analyzing the data provided below highlights three key takeaways.

#1: District Boundaries Create Significant Variations in Property Wealth

Dallas County’s most affluent district, Highland Park ISD, has a tax base that is more than thirteen times greater than its poorest district, Mesquite ISD. The resulting revenue gap between the districts exceeds $900 per pupil even though Mesquite puts forth slightly greater tax effort and has a significantly more challenging student population. Also evident is the arbitrary nature of these boundaries with Highland Park residing within Dallas ISD. Despite the fact that 88% of Dallas’ students are low-income, not one of Highland Park ISD’s 7,054 students falls in this category.

#2: Local Tax Policies have a Strong Effect on Variations in Per-Pupil Spending

Lancaster ISD and Desoto ISD are bordering districts with nearly identical property wealth and similar populations of low-income students, yet the latter taxes at a much higher rate allowing it to raise $656 more per pupil or $13,120 for a class of 20 students. This dynamic can also be observed between Mesquite ISD and Grand Prairie ISD, which raises $706 more per pupil. While some might point to “local control” to justify these differences, decentralization in the 21st century should mean empowering families with robust choice rather than enabling district monopolies.

#3: States Allocate Dollars to Property-Wealthy Districts Despite Existing Funding Gaps

State formulas send Highland Park ISD $769 per pupil even though the district has a large tax base, one of the lowest tax rates in the state and raises more local revenue than every other district in Dallas County. In total, this amounts to over $5 million in state funding that could be allocated more efficiently or simply returned to taxpayers. In fact, every district in Texas—even those subject to the state’s recapture provisions commonly known as “Robin Hood”—receives at least $612 per pupil, regardless of need.

Importantly, funding inequity isn’t the only problem caused by local education revenues. A forthcoming Reason Foundation policy brief will explain in detail why local revenues are incompatible with student-centered funding and how ending this reliance altogether would allow for greater portability, transparency and fiscal accountability—all things that promote school choice.